A Comprehensive Examination of Depressive Disorders: Etiology, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Cross-Cultural Considerations

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

Abstract

Depressive disorders represent a significant global health burden, impacting individuals across all ages, socioeconomic strata, and cultural backgrounds. This research report provides a comprehensive overview of depression, encompassing its multifaceted etiology, diverse diagnostic approaches, evolving treatment modalities, and the crucial role of cultural context in shaping both the manifestation and prevalence of these disorders. We explore the complex interplay of biological, psychological, and sociological factors contributing to the development of depression, delving into the neurobiological underpinnings, cognitive distortions, and environmental stressors that contribute to its pathogenesis. Furthermore, we examine the nuances of differential diagnosis, considering various subtypes of depression and co-occurring conditions. This report also critically evaluates the efficacy and limitations of current treatment strategies, including pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, while highlighting emerging therapeutic avenues. Finally, we address the critical need for culturally sensitive approaches to diagnosis and treatment, acknowledging the significant influence of cultural norms, values, and beliefs on the lived experience of depression. We posit that a holistic and culturally informed understanding of depression is essential for improving the accuracy of diagnosis, the effectiveness of treatment, and ultimately, the well-being of individuals struggling with these debilitating conditions.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

1. Introduction

Depressive disorders are characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, loss of interest or pleasure, and a range of cognitive, behavioral, and somatic symptoms that significantly impair an individual’s ability to function effectively in daily life (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). These disorders are not simply transient periods of sadness or grief; rather, they represent a sustained and debilitating condition that can have profound consequences on an individual’s physical health, mental well-being, social relationships, and overall quality of life. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that depression affects more than 280 million people worldwide, making it a leading cause of disability globally (WHO, 2023). Furthermore, depression is a significant risk factor for suicide, a tragic outcome that underscores the urgent need for improved understanding, prevention, and treatment of these disorders.

While depression can manifest at any age, it is particularly concerning in adolescence, a period of significant developmental change and vulnerability (Costello et al., 2006). The prevalence of depression in adolescents is estimated to be between 5% and 10%, with higher rates observed in females compared to males (Merikangas et al., 2010). This gender disparity may be attributed to a combination of biological, psychological, and social factors, including hormonal fluctuations, differences in coping styles, and exposure to gender-specific stressors. Understanding the specific factors that contribute to depression in adolescents, particularly within different cultural contexts, is crucial for developing targeted prevention and intervention strategies.

This research report aims to provide a comprehensive overview of depressive disorders, encompassing their etiology, diagnosis, treatment, and cross-cultural considerations. By exploring the complex interplay of biological, psychological, and sociological factors, we hope to shed light on the multifaceted nature of depression and inform the development of more effective and culturally sensitive approaches to care.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

2. Etiology of Depressive Disorders

The etiology of depressive disorders is complex and multifactorial, involving a dynamic interplay of biological, psychological, and sociological factors. It is widely accepted that depression does not arise from a single cause, but rather from a combination of predisposing vulnerabilities and environmental stressors.

2.1 Biological Factors

2.1.1 Genetic Predisposition: Twin and family studies have consistently demonstrated a significant genetic component to depression (Sullivan et al., 2000). Individuals with a family history of depression are at a higher risk of developing the disorder themselves, suggesting that certain genes may confer vulnerability. While specific genes responsible for depression have not been definitively identified, research has focused on genes involved in neurotransmitter regulation, stress response, and neuronal plasticity. It’s crucial to note that genes don’t act in isolation; rather, they interact with environmental factors to influence the likelihood of developing depression. The field of epigenetics is also gaining traction, examining how environmental influences can alter gene expression and contribute to the development of mental disorders.

2.1.2 Neurotransmitter Imbalance: The monoamine hypothesis, which posits that depression is caused by a deficiency in certain neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, has been a dominant theory in the field for decades (Schildkraut, 1965). While this hypothesis has been instrumental in the development of antidepressant medications, it is now recognized as an oversimplification. Research suggests that depression involves more complex alterations in neurotransmitter function, including changes in receptor sensitivity, signal transduction pathways, and the interaction between different neurotransmitter systems. Furthermore, other neurotransmitters, such as glutamate and GABA, are increasingly recognized as playing a significant role in the pathophysiology of depression.

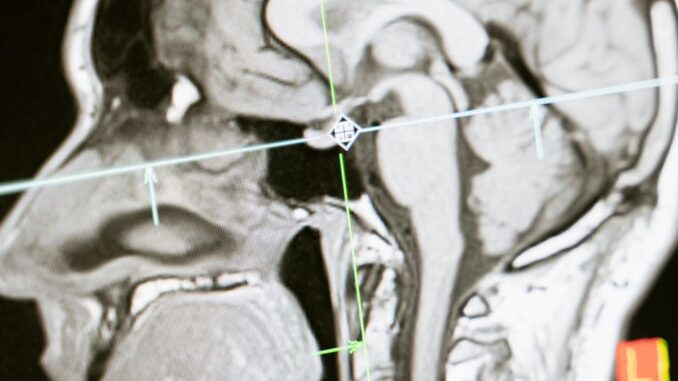

2.1.3 Brain Structure and Function: Neuroimaging studies have revealed structural and functional abnormalities in several brain regions in individuals with depression. These include the prefrontal cortex (involved in executive function and emotional regulation), the hippocampus (involved in memory and learning), the amygdala (involved in processing emotions, particularly fear and anxiety), and the anterior cingulate cortex (involved in conflict monitoring and error detection) (Drevets, 2000). For instance, studies have shown reduced volume in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex in individuals with chronic depression. Furthermore, abnormal activity in the amygdala has been linked to increased emotional reactivity and negative bias in individuals with depression. These findings suggest that disruptions in neural circuitry and brain plasticity contribute to the cognitive and emotional symptoms of depression.

2.1.4 HPA Axis Dysregulation: The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is a key component of the stress response system. In individuals with depression, the HPA axis is often dysregulated, leading to increased levels of cortisol, the primary stress hormone (Holsboer, 2000). Chronic exposure to elevated cortisol can have detrimental effects on the brain, including damage to the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Furthermore, HPA axis dysregulation can disrupt sleep patterns, which are often disturbed in individuals with depression. The link between chronic stress, HPA axis dysregulation, and depression highlights the importance of stress management and resilience-building interventions in the prevention and treatment of depression.

2.2 Psychological Factors

2.2.1 Cognitive Theories: Cognitive theories of depression emphasize the role of negative thinking patterns in the development and maintenance of the disorder. Aaron Beck’s cognitive theory posits that individuals with depression have a negative view of themselves, the world, and the future (Beck, 1967). These negative cognitions, or automatic thoughts, are often based on distorted interpretations of experiences and can lead to feelings of hopelessness and despair. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) aims to identify and challenge these negative thinking patterns, helping individuals to develop more realistic and adaptive ways of thinking. Learned helplessness theory, developed by Martin Seligman, suggests that individuals who experience repeated uncontrollable negative events may develop a sense of helplessness and hopelessness, which can lead to depression (Seligman, 1975). Attributional style, which refers to how individuals explain the causes of events, is also thought to play a role in depression. Individuals with a pessimistic attributional style, who tend to attribute negative events to internal, stable, and global causes, are at higher risk of developing depression.

2.2.2 Attachment Theory: Attachment theory posits that early relationships with caregivers shape an individual’s sense of self and their ability to form secure relationships later in life (Bowlby, 1969). Individuals with insecure attachment styles, such as anxious-preoccupied or dismissive-avoidant, may be more vulnerable to depression, particularly in the context of stressful life events or relationship difficulties. Insecure attachment can lead to difficulties in regulating emotions, forming stable relationships, and seeking social support, all of which can increase the risk of depression. Research has shown that interventions that focus on improving attachment security can be effective in reducing symptoms of depression.

2.2.3 Personality Traits: Certain personality traits have been linked to an increased risk of depression. For example, individuals with high levels of neuroticism, which is characterized by a tendency to experience negative emotions such as anxiety, sadness, and anger, are more likely to develop depression (Kendler et al., 2006). Similarly, individuals with low levels of conscientiousness, which is characterized by a lack of organization, discipline, and goal-directed behavior, may also be at higher risk of depression. These personality traits may influence how individuals cope with stress, form relationships, and pursue their goals, all of which can impact their risk of developing depression.

2.3 Sociological Factors

2.3.1 Stressful Life Events: Stressful life events, such as job loss, relationship breakup, financial difficulties, or the death of a loved one, are major risk factors for depression (Brown & Harris, 1978). The impact of stressful life events on depression can be mediated by a variety of factors, including the individual’s coping skills, social support, and genetic vulnerability. Chronic stress, such as living in poverty or experiencing discrimination, can also increase the risk of depression. The cumulative effect of multiple stressors can be particularly detrimental to mental health. It is important to note that the subjective meaning and interpretation of stressful events can also influence their impact on depression. For example, individuals who perceive a stressful event as uncontrollable or catastrophic may be more likely to develop depression.

2.3.2 Social Support: Social support, which refers to the availability of emotional, informational, and tangible assistance from others, is a protective factor against depression (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Individuals with strong social support networks are better able to cope with stress and are less likely to develop depression. Conversely, social isolation and loneliness are risk factors for depression. Social support can buffer the impact of stressful life events and promote resilience. Interventions that aim to improve social support, such as social skills training and group therapy, can be effective in reducing symptoms of depression.

2.3.3 Cultural Influences: Cultural norms, values, and beliefs can significantly influence the rates and manifestation of depression. In some cultures, depression may be stigmatized, leading individuals to be reluctant to seek help. Cultural differences in the expression of emotions can also affect how depression is recognized and diagnosed. For example, in some cultures, somatic symptoms, such as fatigue and pain, may be more prominent than emotional symptoms, such as sadness and hopelessness. Furthermore, cultural factors can influence the availability and accessibility of mental health services. Culturally sensitive approaches to diagnosis and treatment are essential for addressing the needs of diverse populations. For instance, understanding cultural beliefs about mental illness and incorporating culturally relevant coping strategies can improve the effectiveness of interventions.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

3. Diagnosis of Depressive Disorders

The diagnosis of depressive disorders relies on a comprehensive assessment of an individual’s symptoms, history, and functioning. Clinicians typically use diagnostic criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) to determine whether an individual meets the criteria for a depressive disorder. However, diagnostic accuracy relies heavily on the clinician’s expertise, and a thorough understanding of the patient’s socio-cultural context.

3.1 Diagnostic Criteria

The DSM-5 outlines specific criteria for various depressive disorders, including major depressive disorder (MDD), persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia), and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD). To meet the criteria for MDD, an individual must experience five or more symptoms during the same 2-week period, with at least one of the symptoms being either depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure. Other symptoms may include significant weight loss or gain, insomnia or hypersomnia, psychomotor agitation or retardation, fatigue or loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt, difficulty concentrating, and recurrent thoughts of death or suicide (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The symptoms must cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. Persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia) is characterized by a chronic, low-grade depression that lasts for at least 2 years in adults or 1 year in children and adolescents. DMDD is a childhood disorder characterized by severe and recurrent temper outbursts and persistent irritability or anger.

3.2 Assessment Methods

3.2.1 Clinical Interview: The clinical interview is a crucial component of the diagnostic process. During the interview, the clinician gathers information about the individual’s symptoms, history of mental health problems, family history, current stressors, and social support network. The clinician also observes the individual’s appearance, behavior, and affect to gain a better understanding of their overall presentation. Structured or semi-structured interviews, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5), can be used to ensure that all relevant diagnostic criteria are assessed systematically.

3.2.2 Self-Report Questionnaires: Self-report questionnaires are commonly used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms. These questionnaires typically consist of a series of questions that ask individuals to rate their symptoms on a scale. Examples of commonly used self-report questionnaires include the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Self-report questionnaires can be useful for screening for depression, monitoring treatment progress, and comparing symptom levels across individuals.

3.2.3 Observational Measures: Observational measures can provide valuable information about an individual’s behavior and functioning in real-world settings. For example, clinicians may observe an individual’s interactions with others, their ability to perform daily tasks, and their level of engagement in activities. Observational measures can be particularly useful for assessing depression in individuals who have difficulty communicating or reporting their symptoms. Informant reports, such as those from parents, teachers, or caregivers, can also provide valuable information about an individual’s behavior and functioning.

3.2.4 Physical Examination and Laboratory Tests: While depression is primarily a mental health disorder, it can have physical manifestations. A physical examination may be conducted to rule out any underlying medical conditions that could be contributing to depressive symptoms. Laboratory tests, such as blood tests, may be ordered to assess thyroid function, vitamin deficiencies, and other medical factors that could be related to depression. Identifying and treating any underlying medical conditions can improve the effectiveness of treatment for depression.

3.3 Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis is the process of distinguishing between different disorders that share similar symptoms. It is essential to carefully consider other possible diagnoses before concluding that an individual has a depressive disorder. Some conditions that may mimic depression include bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, medical conditions, and adjustment disorders. Bipolar disorder is characterized by periods of both depression and mania or hypomania. Anxiety disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder and social anxiety disorder, can also cause symptoms of depression, such as fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and irritability. Substance use disorders can also lead to depression, either as a direct result of substance use or as a withdrawal symptom. Medical conditions, such as hypothyroidism and chronic pain, can also cause symptoms of depression. Adjustment disorders are characterized by emotional or behavioral symptoms that develop in response to an identifiable stressor. It is crucial to carefully assess the individual’s history, symptoms, and functioning to determine the most accurate diagnosis.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

4. Treatment of Depressive Disorders

The treatment of depressive disorders typically involves a combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. The specific treatment approach will depend on the severity of the depression, the individual’s preferences, and the availability of resources. A collaborative approach, involving the individual, their family, and a team of healthcare professionals, is essential for successful treatment.

4.1 Psychotherapy

4.1.1 Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a widely used and effective treatment for depression (Beck, 1967). CBT focuses on identifying and changing negative thinking patterns and behaviors that contribute to depression. Individuals learn to recognize their negative automatic thoughts and to challenge them with more realistic and adaptive thoughts. They also learn to identify and modify maladaptive behaviors, such as avoidance and social withdrawal. CBT typically involves a structured, time-limited approach, with specific goals and homework assignments. Research has consistently shown that CBT is effective in reducing symptoms of depression and preventing relapse.

4.1.2 Interpersonal Therapy (IPT): Interpersonal therapy (IPT) focuses on improving an individual’s relationships and social functioning (Klerman et al., 1984). IPT is based on the premise that depression is often related to interpersonal problems, such as grief, role disputes, role transitions, and interpersonal deficits. Individuals learn to identify and address these interpersonal problems, improving their relationships and reducing their symptoms of depression. IPT typically involves a structured, time-limited approach, with a focus on improving communication skills, assertiveness, and social support. Research has shown that IPT is effective in treating depression, particularly when interpersonal problems are a significant contributing factor.

4.1.3 Psychodynamic Therapy: Psychodynamic therapy explores unconscious conflicts and early childhood experiences that may be contributing to depression. Individuals learn to gain insight into their emotions and behaviors, and to develop more adaptive coping mechanisms. Psychodynamic therapy typically involves a longer-term approach than CBT or IPT, with a focus on exploring the individual’s past and present relationships. While less research has been conducted on the effectiveness of psychodynamic therapy for depression compared to CBT and IPT, some studies have shown that it can be beneficial for certain individuals.

4.2 Pharmacotherapy

4.2.1 Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most commonly prescribed class of antidepressants. SSRIs work by increasing the levels of serotonin in the brain. Common SSRIs include fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram, and escitalopram. SSRIs are generally well-tolerated, but they can cause side effects such as nausea, insomnia, sexual dysfunction, and weight gain. SSRIs are effective in treating a wide range of depressive disorders, including MDD, persistent depressive disorder, and anxiety disorders with co-occurring depression.

4.2.2 Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs): Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) work by increasing the levels of both serotonin and norepinephrine in the brain. Common SNRIs include venlafaxine, duloxetine, and desvenlafaxine. SNRIs are generally considered to be slightly more effective than SSRIs for some individuals, but they may also have a higher risk of side effects. SNRIs can cause side effects such as nausea, insomnia, sexual dysfunction, weight gain, and increased blood pressure.

4.2.3 Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs): Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are an older class of antidepressants that work by increasing the levels of serotonin and norepinephrine in the brain. Common TCAs include amitriptyline, nortriptyline, and imipramine. TCAs are effective in treating depression, but they have a higher risk of side effects than SSRIs and SNRIs. TCAs can cause side effects such as dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, urinary retention, and orthostatic hypotension. Due to their potential for serious side effects, TCAs are typically reserved for individuals who have not responded to other antidepressants.

4.2.4 Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs): Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are an older class of antidepressants that work by inhibiting the enzyme monoamine oxidase, which breaks down serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine in the brain. Common MAOIs include phenelzine, tranylcypromine, and isocarboxazid. MAOIs are effective in treating depression, but they have a high risk of serious side effects and drug interactions. Individuals taking MAOIs must adhere to a strict dietary regimen to avoid consuming foods that contain tyramine, which can cause a dangerous increase in blood pressure. Due to their potential for serious side effects, MAOIs are typically reserved for individuals who have not responded to other antidepressants.

4.3 Other Treatments

4.3.1 Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT): Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a treatment that involves inducing a brief seizure by passing an electrical current through the brain. ECT is typically reserved for individuals with severe depression who have not responded to other treatments. ECT is effective in relieving symptoms of depression, but it can cause side effects such as memory loss and confusion.

4.3.2 Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS): Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a non-invasive treatment that involves using magnetic pulses to stimulate specific areas of the brain. TMS is typically used to treat individuals with depression who have not responded to other treatments. TMS is generally well-tolerated, but it can cause side effects such as headache and scalp discomfort.

4.3.3 Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS): Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is a treatment that involves implanting a device that stimulates the vagus nerve, which is a major nerve that connects the brain to the body. VNS is typically used to treat individuals with depression who have not responded to other treatments. VNS is generally well-tolerated, but it can cause side effects such as hoarseness, cough, and shortness of breath.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

5. Cross-Cultural Considerations

Cultural factors play a significant role in the manifestation, diagnosis, and treatment of depression. Cultural norms, values, and beliefs can influence how individuals experience and express their symptoms, how they seek help, and how they respond to treatment. It is essential to consider these cultural factors when working with individuals from diverse backgrounds to ensure that they receive culturally sensitive and effective care.

5.1 Cultural Variations in Symptom Presentation

Cultural variations exist in the way individuals experience and express symptoms of depression. In some cultures, somatic symptoms, such as fatigue, pain, and digestive problems, may be more prominent than emotional symptoms, such as sadness and hopelessness (Kleinman, 1982). This may be due to cultural norms that discourage the expression of emotions or to a greater emphasis on physical well-being. In other cultures, depression may be expressed through social withdrawal, irritability, or anger. It is important for clinicians to be aware of these cultural variations in symptom presentation to avoid misdiagnosis and to provide culturally appropriate care.

5.2 Cultural Stigma and Help-Seeking Behaviors

The stigma associated with mental illness can be a significant barrier to help-seeking for individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds. In some cultures, mental illness is viewed as a sign of weakness or personal failure, and individuals may be reluctant to seek help for fear of shame or discrimination. Cultural beliefs about the causes of mental illness can also influence help-seeking behaviors. For example, some cultures may attribute mental illness to supernatural causes, such as witchcraft or evil spirits, and individuals may seek help from traditional healers rather than mental health professionals. It is important for clinicians to address the stigma associated with mental illness and to promote culturally appropriate education about mental health to encourage individuals to seek help when they need it.

5.3 Culturally Adapted Interventions

Culturally adapted interventions are interventions that have been modified to be more culturally relevant and acceptable to individuals from diverse backgrounds. These adaptations may involve changes to the language, content, or delivery method of the intervention. For example, a culturally adapted CBT intervention for depression may incorporate cultural values and beliefs into the treatment process, use culturally relevant examples, and address cultural barriers to treatment. Research has shown that culturally adapted interventions can be more effective than standard interventions for individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

6. Conclusion

Depressive disorders are a significant public health concern, impacting millions of people worldwide. A comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted etiology, diverse diagnostic approaches, evolving treatment modalities, and crucial role of cultural context is essential for improving outcomes. While pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions have demonstrated efficacy, the evolving landscape of neuroscience and genetics promises to refine our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of depression and pave the way for novel, targeted therapies. Recognizing the cultural nuances that influence the expression and experience of depression is paramount for providing culturally sensitive and effective care. Future research should prioritize the development and evaluation of culturally adapted interventions and the implementation of evidence-based practices in diverse settings to reduce the global burden of depressive disorders.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

- Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss, Vol. 1: Attachment. Attachment and Loss. New York: Basic Books.

- Brown, G. W., & Harris, T. O. (1978). Social origins of depression: A study of psychiatric disorder in women. Tavistock Publications.

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310-357.

- Costello, E. J., Mustillo, S., Erkanli, A., Keeler, G., & Angold, A. (2006). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(7), 717-726.

- Drevets, W. C. (2000). Neuroimaging and neuropathological studies of depression: Implications for the cognitive-emotional features of depressive disorders. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 11(2), 240-249.

- Holsboer, F. (2000). The corticosteroid receptor hypothesis of depression. Neuropsychopharmacology, 23(5), 477-501.

- Kendler, K. S., Gatz, M., Gardner, C. O., & Pedersen, N. L. (2006). Personality and major depression: a Swedish longitudinal, population-based twin study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(2), 113-121.

- Kleinman, A. (1982). Neurasthenia and other forms of distress in primary care. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 6(4), 429-458.

- Klerman, G. L., Weissman, M. M., Rounsaville, B. J., & Chevron, E. S. (1984). Interpersonal psychotherapy of depression. Basic Books.

- Merikangas, K. R., He, J. P., Burstein, M., Swanson, S. A., Avenevoli, S., Cui, L., … & Swendsen, J. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980-989.

- Schildkraut, J. J. (1965). The catecholamine hypothesis of affective disorders: A review of supporting evidence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 122(5), 509-522.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (1975). Helplessness: On depression, development, and death. W. H. Freeman.

- Sullivan, P. F., Neale, M. C., & Kendler, K. S. (2000). Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(10), 1552-1562.

- World Health Organization. (2023). Depression. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

This report highlights the critical need for culturally sensitive approaches. Exploring specific adaptations of CBT or IPT for different cultural groups could significantly improve treatment outcomes and reduce mental health disparities.