Abstract

Local Field Potentials (LFPs) represent a fundamental aspect of neuronal ensemble activity, serving as extracellular electrical signatures that encapsulate the synchronized synaptic processing within a specific brain region. Their profound utility in deciphering brain function has been increasingly recognized, particularly in the advancement of Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) therapies for a spectrum of debilitating neurological disorders. This comprehensive report undertakes an in-depth exploration of the neurophysiological underpinnings of LFPs, meticulously detailing their generation mechanisms, advanced recording and analysis methodologies, and their critical significance across various pathological states within the nervous system. Furthermore, it scrutinizes the inherent challenges and burgeoning advancements in harnessing LFPs for sophisticated real-time neuromodulation strategies and innovative brain-computer interfaces (BCIs). A particular focus is dedicated to the groundbreaking integration of LFP sensing capabilities within modern adaptive DBS (aDBS) systems, exemplified by Medtronic’s BrainSense™ technology, which heralds a new era of personalized neurotherapeutics.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

1. Introduction

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) has transcended its initial experimental phase to become a cornerstone therapeutic intervention, offering substantial symptomatic relief for individuals afflicted by chronic, treatment-refractory neurological conditions such as Parkinson’s disease (PD), essential tremor (ET), and dystonia. Pioneered in the late 1980s, traditional DBS operates as an open-loop system, delivering continuous electrical stimulation to precisely targeted brain regions – commonly the subthalamic nucleus (STN) or globus pallidus internus (GPi) for PD – with fixed parameters (e.g., amplitude, pulse width, frequency). While undeniably effective, this conventional approach is characterized by several inherent limitations: the energy-intensive nature of continuous stimulation often necessitates frequent battery replacements; the static parameters may lead to suboptimal symptom control as a patient’s condition fluctuates throughout the day or progresses over time; and the potential for stimulation-induced side effects, such as dysarthria or gait disturbances, can arise from overstimulation or stimulation that is not precisely tailored to the moment-to-moment needs of the brain.

Recognizing these limitations, the scientific and clinical communities have driven a relentless pursuit of more refined, responsive neuromodulation paradigms. This endeavor has culminated in the emergence of sensing-enabled DBS systems, which represent a paradigm shift towards personalized medicine in neurological care. These innovative systems are endowed with the capacity to not only deliver therapeutic stimulation but also to monitor real-time brain activity, thereby offering an unprecedented window into the brain’s functional state. Among the myriad neurophysiological signals available for monitoring, Local Field Potentials (LFPs) have emerged as particularly potent and clinically relevant biomarkers. LFPs, as macroscopic reflections of synchronized synaptic activity within a neuronal population, encapsulate critical information regarding the pathological oscillations characteristic of many neurological disorders.

Medtronic’s BrainSense™ Adaptive Deep Brain Stimulation (aDBS) system stands as a quintessential illustration of this technological revolution. By leveraging the continuous, real-time acquisition and analysis of LFPs, the system is designed to dynamically adjust stimulation parameters in response to instantaneous changes in a patient’s brain activity. This closed-loop approach moves beyond the static nature of conventional DBS, promising enhanced therapeutic efficacy, reduced stimulation-induced side effects, and potentially extended battery life. The integration of LFP sensing within DBS technology fundamentally transforms the therapeutic landscape, shifting from a generic, one-size-fits-all model to a highly individualized, demand-driven neuromodulation strategy that adapts to the unique and fluctuating needs of each patient. This report aims to elucidate the intricate details behind this transformative technology and its profound implications for neurological care.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

2. Neurophysiological Basis of Local Field Potentials

2.1 Generation Mechanisms

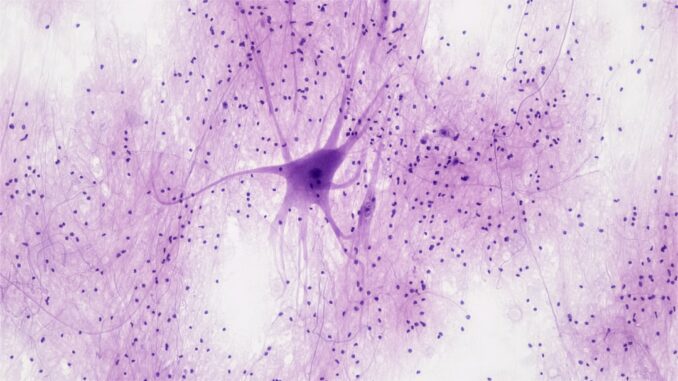

Local Field Potentials are not merely arbitrary electrical noise; rather, they are complex, low-frequency extracellular electrical signals (typically below 500 Hz, often concentrating below 200 Hz) that fundamentally reflect the aggregate, synchronized synaptic activity within a localized neuronal population. To truly appreciate their significance, it is crucial to delve into the biophysical mechanisms underlying their generation. Unlike the high-frequency, all-or-none action potentials (spikes) which represent the output of individual neurons, LFPs primarily arise from the graded, subthreshold transmembrane currents associated with synaptic inputs and intrinsic neuronal oscillations, which subsequently summate in the extracellular space.

When a large ensemble of neurons, particularly those with spatially aligned dendritic trees such as cortical pyramidal neurons, receives synchronous synaptic inputs, these inputs generate postsynaptic potentials (PSPs) – either excitatory (EPSPs) or inhibitory (IPSPs). These PSPs cause transient influxes or effluxes of ions (e.g., Na+, K+, Cl-) across the neuronal membrane at specific locations, such as dendrites or somata. This localized ion movement creates localized electrical current sources and sinks within the neuron. For example, an excitatory input to a dendrite will cause a local influx of positive ions, creating a current sink in that region and a compensatory current source further away along the membrane, as charge flows to complete the circuit. These intracellular current flows then spread into the extracellular space, creating extracellular potential gradients that can be detected by recording electrodes. It is the summation of these extracellular currents from thousands to millions of neurons within a several hundred-micrometer radius of the electrode tip that constitutes the LFP signal. The magnitude and polarity of the recorded LFP depend critically on the spatial arrangement and synchronous activation of these neuronal elements, the orientation of their dendrites relative to the electrode, and the timing and location of synaptic inputs. Importantly, the LFP is a band-limited signal, reflecting slow potential changes, distinct from the faster action potentials that contribute only minimally and indirectly to the overall LFP power, primarily through their influence on synaptic events.

2.2 Cellular-Level Mechanisms and Synaptic Contributions

At the microscopic cellular level, the LFP is understood as a weighted sum of transmembrane currents generated by a diverse array of biophysical processes. While action potentials certainly signify neuronal firing, their contribution to the LFP is often considered secondary, primarily through their role in initiating neurotransmitter release and thus subsequent synaptic potentials in downstream neurons. The dominant contributors to LFPs are the dendritic postsynaptic currents, encompassing both EPSPs and IPSPs.

- Excitatory Postsynaptic Potentials (EPSPs): These are depolarizing potentials typically mediated by neurotransmitters such like glutamate binding to ionotropic receptors (e.g., AMPA, NMDA receptors) or metabotropic receptors. The activation of AMPA receptors, for instance, leads to an influx of Na+ ions, causing a localized current sink at the dendrite where the synapse is located, with a corresponding current source distributed across other parts of the neuron, particularly the soma and axon. This extracellular current flow generates the positive or negative deflection observed in the LFP, depending on the electrode’s position relative to the current source/sink configuration.

- Inhibitory Postsynaptic Potentials (IPSPs): These are hyperpolarizing or shunting potentials, often mediated by GABAergic neurotransmission, typically involving an influx of Cl- ions (via GABA-A receptors) or an efflux of K+ ions (via GABA-B receptors). Similar to EPSPs, IPSPs create local current sinks or sources that contribute to the extracellular field, albeit with potentially different spatiotemporal profiles and polarities.

The precise contribution of these synaptic events to the LFP signal is profoundly influenced by several factors:

- Neuronal Morphology and Orientation: Pyramidal neurons, abundant in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, are particularly effective LFP generators due to their elongated, parallel-aligned dendritic trees. Synaptic inputs arriving at different locations along these dendrites create spatially segregated current sources and sinks, establishing an ‘open field’ configuration that allows the extracellular currents to propagate over relatively large distances, making them readily detectable. In contrast, neurons with radially symmetric dendritic arbors tend to create ‘closed fields’ where current sources and sinks are spatially intermingled and cancel each other out in the extracellular space, thus contributing less to the macroscopic LFP.

- Synchronicity of Input: For PSPs to generate a detectable LFP, a sufficient number of neurons must receive synchronous synaptic inputs within a limited spatial and temporal window. Highly asynchronous activity tends to cancel out in the extracellular summation.

- Intrinsic Membrane Properties: The passive and active electrical properties of neuronal membranes, including the distribution and density of various voltage-gated ion channels (e.g., Na+, K+, Ca2+ channels) and ligand-gated receptors, modulate the neuronal response to synaptic inputs. These intrinsic properties can also give rise to intrinsic neuronal oscillations, which can further synchronize populations of neurons and directly contribute to LFP rhythms.

- Glial Cell Activity: While often overlooked, glial cells (astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia) also play a role in shaping the extracellular ionic environment and neurotransmitter concentrations, indirectly influencing synaptic transmission and neuronal excitability, and thus potentially modulating LFP characteristics. They can also generate slow intrinsic potential changes.

Understanding these intricate cellular and network-level mechanisms is paramount for accurately interpreting LFP data. Pathological alterations in synaptic strength, neuronal excitability, or network synchronicity, as seen in disorders like Parkinson’s disease, directly manifest as changes in LFP characteristics, providing critical biomarkers for diagnosis, monitoring, and therapeutic intervention.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

3. Recording and Analysis of Local Field Potentials

The utility of LFPs as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool hinges on the ability to accurately record and meticulously analyze these complex signals. This section delves into the technical aspects of LFP acquisition and the sophisticated signal processing techniques employed to extract meaningful neurophysiological insights.

3.1 Recording Techniques

The fidelity of LFP recordings is critically dependent on the choice and placement of electrodes, as well as the recording montage. In the context of DBS, electrodes are strategically implanted within deep brain structures known to be involved in the pathophysiology of specific disorders.

- Electrode Characteristics: LFPs are typically recorded using macroelectrodes or multi-contact electrodes, which are designed to capture activity from a larger population of neurons compared to microelectrodes used for single-unit recordings. The materials are biocompatible and conductive, often platinum-iridium or tungsten, ensuring minimal tissue reaction and stable impedance over time. DBS leads, such as Medtronic’s Percept™ PC or Activa™ RC, are equipped with multiple (e.g., 4 or 8) cylindrical contacts arranged along the shaft, allowing for flexible configuration of sensing and stimulation.

- Surgical Implantation: The implantation of DBS electrodes is a highly specialized neurosurgical procedure, typically performed using stereotactic guidance. Preoperative imaging (MRI, CT) is used to create a precise 3D map of the patient’s brain, identifying the target nucleus (e.g., STN, GPi, VIM of the thalamus). During surgery, electrophysiological mapping, which involves recording single-unit activity and/or LFPs, often guides the final electrode placement, ensuring optimal therapeutic benefit and minimizing side effects. This intraoperative recording is crucial for ‘micro-electrode recording’ (MER), which can help identify the boundaries of target nuclei and areas of pathological activity. Once the optimal trajectory and depth are confirmed, the DBS lead is permanently implanted.

- Recording Montages: The configuration of the recording electrodes, known as the montage, significantly impacts the spatial specificity and signal-to-noise ratio of the recorded LFP.

- Monopolar Recording: In a monopolar setup, the LFP is recorded from a single active electrode contact relative to a distant, indifferent reference electrode (e.g., an electrode on the skull or a metallic housing of the implantable pulse generator, IPG). While this montage can yield signals of higher amplitude, it is highly susceptible to common-mode noise (electrical interference affecting both active and reference electrodes) and volume conduction from distant brain regions, leading to a broader, less spatially specific signal.

- Bipolar Recording: For DBS applications, bipolar recording montages are frequently preferred. Here, the LFP is recorded as the voltage difference between two adjacent contacts on the same DBS lead (e.g., contact 0 vs. contact 1). This configuration offers several advantages: it significantly enhances spatial specificity by emphasizing local potential gradients, effectively rejecting common-mode noise (as both contacts are subject to similar distant influences), and providing a clearer representation of activity within a confined neuronal population directly between the two contacts. This localized information is crucial for identifying the precise anatomical location of pathological oscillations, such as the beta band activity in the STN of Parkinson’s patients. Modern DBS systems allow for flexible programming of both stimulation and sensing contacts, enabling highly customized bipolar LFP sensing.

- Filtering and Sampling: Raw LFP signals typically contain a broad range of frequencies and noise. Analog filters are employed during recording to remove very low-frequency drift (DC components) and very high-frequency noise, setting the bandwidth of interest. Subsequently, the analog signal is digitized using an analog-to-digital converter (ADC) at a sufficiently high sampling rate (e.g., 250-1000 Hz for LFPs, much higher for spikes) to avoid aliasing, in accordance with the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem. Anti-aliasing filters are applied before digitization.

3.2 Analysis Methods

The raw LFP signal is inherently complex, requiring sophisticated signal processing techniques to extract biologically meaningful information. These methods can broadly be categorized into time-domain, frequency-domain, and connectivity analyses.

-

Preprocessing: Before any advanced analysis, raw LFP data undergoes critical preprocessing steps. This includes:

- Noise Reduction: Application of digital filters (e.g., bandpass filters to isolate desired frequency ranges, notch filters to remove mains hum at 50/60 Hz).

- Artifact Rejection: Identification and removal or attenuation of non-neuronal artifacts, such as muscle activity (electromyography, EMG), movement artifacts, eye blinks, cardiac activity, and importantly, stimulation artifacts in closed-loop DBS systems. Advanced algorithms like Independent Component Analysis (ICA) or adaptive filtering can be used for artifact separation.

- Re-referencing: Re-referencing strategies (e.g., common average reference) can further enhance signal quality by minimizing common noise components.

-

Time-Domain Analysis: This approach examines the LFP signal directly in the time domain, focusing on transient changes in voltage in response to specific events or stimuli.

- Event-Related Potentials (ERPs) and Evoked Potentials (EPs): These are averaged brain responses time-locked to a specific sensory, motor, or cognitive event (e.g., initiation of a movement, presentation of a stimulus). By averaging multiple trials, random background noise is attenuated, revealing consistent neural responses. In the context of DBS, changes in ERP components (e.g., readiness potential preceding movement, P300 component related to cognitive processing) can be monitored to assess brain function and the impact of stimulation.

-

Frequency-Domain Analysis: This is arguably the most common and informative approach for LFP analysis, as brain activity is often characterized by rhythmic, oscillatory patterns within specific frequency bands.

- Fourier Transform (FT) and Fast Fourier Transform (FFT): These mathematical tools decompose a time-domain signal into its constituent frequencies, revealing the power (amplitude squared) at each frequency. The resulting Power Spectral Density (PSD) plot shows how power is distributed across different frequencies.

- Spectrograms and Wavelet Transforms: To analyze how frequency content changes over time (e.g., during a movement or a cognitive task), time-frequency analysis methods like short-time Fourier transform (STFT) or wavelet transforms are employed. Wavelet transforms are particularly adept at capturing transient oscillations, providing excellent temporal and spectral resolution simultaneously. These techniques generate spectrograms, which visually represent power as a function of time and frequency.

- Key Frequency Bands: Specific frequency bands are associated with distinct brain states and functions:

- Delta (0.5-4 Hz): Deep sleep, pathological states (e.g., coma, brain lesions).

- Theta (4-8 Hz): Memory processing, navigation, sleep (REM), pathological in awake state.

- Alpha (8-13 Hz): Relaxed wakefulness, sensory gating, pathological in some movement disorders.

- Beta (13-30 Hz): Motor planning/maintenance, sensory processing, strongly linked to motor symptoms in PD. Its desynchronization often precedes voluntary movement.

- Gamma (30-100+ Hz): Active information processing, cognitive tasks, attention, perception. Often associated with movement initiation in PD.

-

Connectivity Analysis: Beyond analyzing power within single brain regions, understanding how different brain areas communicate and coordinate their activity is crucial.

- Coherence: This metric quantifies the linear statistical dependency (synchronization) between two LFP signals in the frequency domain. High coherence at a particular frequency suggests that two brain regions are oscillating together at that frequency, implying functional connectivity. It can be used to assess the coupling between deep brain structures and cortical areas.

- Phase-Amplitude Coupling (PAC): A more sophisticated measure of cross-frequency coupling, PAC assesses how the phase of a low-frequency oscillation modulates the amplitude of a high-frequency oscillation (e.g., theta-gamma coupling). This mechanism is thought to play a vital role in organizing information flow and multiplexing neural computations, and alterations are observed in neurological disorders.

- Granger Causality and Transfer Entropy: These advanced techniques aim to infer directed causality or information flow between different LFP signals, moving beyond mere correlation to suggest which signal ‘leads’ or influences another.

These diverse analytical approaches are indispensable for researchers and clinicians alike, allowing for a profound understanding of LFP dynamics in both physiological and pathological contexts, and critically informing the development and refinement of adaptive neuromodulation strategies.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

4. Significance of LFP Frequency Bands in Neurological Disorders

The ability to record and analyze LFPs has revolutionized our understanding of the pathophysiology of neurological disorders, providing objective biomarkers that correlate with disease state and symptom severity. The identification of specific LFP oscillatory patterns associated with particular disorders has paved the way for highly targeted adaptive DBS therapies.

4.1 Parkinson’s Disease (PD)

Parkinson’s disease, a progressive neurodegenerative disorder, is characterized by the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra, leading to profound motor symptoms such as bradykinesia (slowness of movement), rigidity, tremor, and postural instability. The hallmark neurophysiological signature of PD, particularly in the off-medication state, is a prominent and sustained increase in beta band (13-30 Hz) oscillatory activity within the basal ganglia-thalamocortical motor circuit, specifically observed in the subthalamic nucleus (STN) and globus pallidus internus (GPi).

- The Pathological Beta Rhythm: This ‘pathological beta’ is hypothesized to represent an overly synchronized, ‘idling’ state of the motor system, hindering the ability to initiate and execute voluntary movements. Its amplitude significantly correlates with the severity of bradykinesia and rigidity. When patients are administered dopaminergic medication (e.g., levodopa) or receive effective DBS, this exaggerated beta activity is suppressed, leading to an improvement in motor symptoms. Conversely, a rebound in beta activity often precedes the return of symptoms as medication wears off or stimulation becomes suboptimal.

- Role in Adaptive DBS: Medtronic’s BrainSense™ aDBS system and similar technologies are specifically designed to leverage this beta band biomarker. By continuously monitoring LFP beta power in the STN or GPi, the system can detect when pathological beta activity becomes elevated, indicating a worsening of motor symptoms. In response, the system automatically increases stimulation parameters (e.g., amplitude), thereby suppressing the beta rhythm and alleviating symptoms. Conversely, when beta activity is low (e.g., during active movement or optimal medication effect), the system can reduce or even momentarily turn off stimulation, conserving battery life and minimizing stimulation-induced side effects. This closed-loop feedback mechanism allows for real-time, demand-driven therapy, moving away from continuous, fixed-parameter stimulation. Clinical trials and real-world data have increasingly demonstrated the superior efficacy of aDBS over conventional DBS in terms of symptom control, reduction in stimulation-induced side effects, and enhanced quality of life for PD patients (Medtronic, 2025).

- Other LFP Signatures in PD: Beyond the beta band, other LFP patterns are also being investigated. Gamma band (60-90 Hz) activity, particularly high-frequency gamma, is often associated with voluntary movement initiation and may represent an ‘active’ state of the motor system. In PD, the balance between beta and gamma activity is disrupted, with pathological beta dominating. Research is exploring complex interactions like phase-amplitude coupling between theta and gamma, or beta and gamma, which could provide even more refined biomarkers for aDBS algorithms. Alpha band (8-13 Hz) oscillations can also be observed, sometimes correlating with sensory processing deficits or specific tremor components.

4.2 Essential Tremor (ET)

Essential tremor is one of the most common movement disorders, characterized by an involuntary, rhythmic shaking, typically affecting the hands and arms, but also the head, voice, and legs. Unlike PD, ET is not primarily a basal ganglia disorder but is thought to involve dysfunctional oscillatory networks within the cerebello-thalamo-cortical circuit, particularly the ventral intermediate nucleus (VIM) of the thalamus.

- Tremor-Related Oscillations: LFPs recorded from the VIM of ET patients exhibit characteristic tremor-related oscillations, typically in the 4-12 Hz range, which directly correspond to the frequency of the overt physical tremor. These oscillations are highly coherent between the VIM and the contralateral motor cortex, suggesting a synchronized, pathological loop driving the tremor.

- LFP-Guided DBS in ET: The analysis of these specific LFP oscillations is invaluable for guiding the precise placement of DBS electrodes within the VIM. Intraoperative recordings can pinpoint the region where these tremor-related oscillations are most prominent, allowing neurosurgeons to place the lead optimally. Post-operatively, LFP monitoring can assist in refining DBS programming, ensuring that stimulation effectively disrupts these pathological oscillations without inducing adverse effects. While the primary biomarker for aDBS in ET is still under active research, the consistent presence of tremor-related oscillations makes LFPs a critical tool for understanding and treating this condition.

4.3 Dystonia

Dystonia is a neurological movement disorder characterized by sustained or intermittent muscle contractions causing abnormal, often repetitive, movements and postures. Its pathophysiology is complex, involving abnormal functioning of the basal ganglia, cerebellum, and motor cortex, leading to disrupted sensorimotor integration and aberrant motor pattern generation.

- Altered LFP Patterns in Dystonia: LFP studies in dystonic patients implanted with DBS electrodes (typically in the GPi or STN) have revealed distinct oscillatory patterns that correlate with dystonic symptoms. These include:

- Abnormal Beta and Gamma Activity: Similar to PD, but with different characteristics, altered beta and gamma band activity is observed. There can be a reduction in beta desynchronization during movement, or an abnormal increase in low-frequency oscillations (e.g., delta-theta range), as well as changes in gamma power and phase-amplitude coupling.

- Pathological Synchronization: Dystonia is often associated with abnormal neuronal synchronization, which can manifest as increased coherence between basal ganglia structures and cortical areas in specific frequency bands.

- Challenges and Promise for aDBS: Targeted modulation of these identified frequency bands through DBS has shown promise in alleviating dystonic postures and movements. However, developing LFP-based aDBS for dystonia presents unique challenges compared to PD. Dystonic symptoms are often more complex, fluctuate less predictably, and respond to DBS with a significant delay (weeks to months) rather than immediately. This slower therapeutic response makes direct, real-time feedback based solely on LFP oscillations more difficult to implement. Nevertheless, ongoing research is exploring more complex LFP biomarkers, such as changes in cross-frequency coupling or specific spectral patterns, that could serve as robust control signals for adaptive DBS in dystonia.

4.4 Other Neurological Disorders

The utility of LFPs extends beyond classic movement disorders.

- Epilepsy: LFPs are crucial in epilepsy research and treatment, where abnormal high-amplitude, low-frequency oscillations, interictal spikes, and seizure onset zone activity can be identified. Closed-loop DBS or responsive neurostimulation (RNS) systems use LFP detection to deliver stimulation only when pathological activity is detected, preventing or aborting seizures.

- Tourette Syndrome (TS) and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD): In these neuropsychiatric disorders, DBS targets are often in the basal ganglia or limbic circuits (e.g., nucleus accumbens, anterior cingulate cortex). LFP changes in specific frequency bands (e.g., theta, alpha, beta, gamma) are being investigated as biomarkers for tics in TS or compulsive behaviors in OCD, paving the way for adaptive neuromodulation in these complex conditions.

In summary, the specific LFP frequency bands and their dynamic changes serve as powerful, objective biomarkers for a growing number of neurological disorders. Their real-time monitoring capability is transforming DBS from a static intervention into a dynamic, personalized therapy, leading to improved patient outcomes.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

5. Challenges and Advancements in Real-Time Neuromodulation

The vision of fully adaptive, closed-loop neuromodulation, while tantalizingly close, is accompanied by a host of intricate challenges that demand continuous innovation across engineering, neurophysiology, and clinical science. Simultaneously, remarkable advancements are being made to overcome these hurdles, pushing the boundaries of what is possible in treating neurological disorders.

5.1 Signal Interpretation and Noise Reduction

The fundamental challenge in real-time LFP-based neuromodulation lies in accurately interpreting the brain’s subtle electrical signals amidst a backdrop of physiological noise and technical artifacts. The brain itself is an inherently noisy system, and recording from implanted devices introduces additional layers of complexity.

- Sources of Noise and Artifacts:

- Physiological Noise: Muscle activity (electromyography, EMG) from facial or neck muscles, particularly during movement, can contaminate LFP signals, especially in superficial brain regions. Eye blinks and saccades generate electrooculographic (EOG) artifacts. Cardiac activity (ECG) can also introduce rhythmic noise.

- Movement Artifacts: Patient movement, even subtle head movements, can cause electrode impedance changes or relative movement between the electrode and brain tissue, leading to large, transient voltage deflections that obscure neural signals.

- Stimulation Artifacts: In DBS systems, the very act of delivering therapeutic electrical pulses generates a large, wideband artifact that can completely saturate the recording amplifier, making it impossible to sense neural activity during or immediately after the stimulation pulse. This is often referred to as the ‘stimulation artifact’ or ‘swimming artifact’. Overcoming this is critical for true closed-loop operation.

- Environmental Electrical Interference: Power line noise (50/60 Hz mains hum), radiofrequency interference, and other electromagnetic fields from medical equipment or personal devices can corrupt LFP recordings.

- Advanced Filtering and Artifact Rejection: To address these challenges, sophisticated signal processing techniques are essential:

- Digital Filtering: Bandpass filters are used to isolate the frequency range of interest (e.g., 1-100 Hz for LFPs). Notch filters are highly effective at removing specific line noise frequencies.

- Adaptive Filtering: These algorithms dynamically adjust their filter characteristics to remove noise while preserving the underlying neural signal, particularly useful for non-stationary noise sources.

- Independent Component Analysis (ICA): ICA can blindly separate mixed signals into statistically independent components, allowing for the extraction of neural activity from artifactual components.

- Stimulation Artifact Suppression: This is a key area of innovation. Techniques include:

- Blanking/Gating: Momentarily turning off the sensing amplifier during stimulation pulses, though this leads to data loss.

- Analog/Digital Cancellation: Using matched filters or adaptive algorithms to subtract a template of the artifact from the recorded signal.

- Alternating Sensing and Stimulation: Medtronic’s BrainSense™, for instance, records LFPs between stimulation pulses, or during brief ‘sensing windows’ inserted into the stimulation train, carefully coordinated to minimize artifact intrusion (Medtronic, 2025). This allows for near-continuous, albeit interleaved, monitoring.

- Common Average Re-referencing (CAR): While bipolar montages inherently provide some common-mode rejection, CAR can further reduce widespread noise by subtracting the average activity across multiple electrodes from each individual electrode’s signal.

5.2 Individual Variability and Personalization

The human brain is remarkably diverse, and neurological disorders manifest with significant inter-individual variability in terms of symptoms, disease progression, underlying neurophysiology, and response to therapy. This inherent variability necessitates personalized approaches to DBS programming and LFP interpretation.

- Factors Contributing to Variability:

- Anatomical Differences: Subtle variations in brain structure and target nucleus geometry between individuals.

- Disease Phenotype and Stage: Different motor symptoms (tremor-dominant vs. bradykinesia/rigidity dominant PD) and varying disease progression rates.

- Medication Effects: The interaction between dopaminergic medication and DBS, and how both influence LFP patterns.

- Individual Response to Stimulation: The optimal stimulation parameters and their effects on LFP biomarkers can differ substantially from patient to patient.

- The Role of Personalized Medicine: Adaptive DBS systems must move beyond generic algorithms to account for these variations to truly optimize therapeutic outcomes. This means developing algorithms that can ‘learn’ an individual’s unique neural signatures and their correlation with clinical state.

- Advanced Machine Learning and AI:

- Biomarker Discovery: Machine learning algorithms are increasingly being employed to analyze large, longitudinal datasets of LFPs. These algorithms can identify subtle, complex LFP features (beyond simple beta power) or combinations of features that serve as more robust biomarkers for specific symptoms or clinical states.

- Predictive Modeling: AI models can learn to predict changes in motor state (e.g., ‘on’ vs. ‘off’ medication, dyskinesia onset) from LFP patterns, enabling proactive rather than reactive stimulation adjustments.

- Reinforcement Learning: This paradigm allows the aDBS system to ‘learn’ optimal stimulation strategies through trial and error, adjusting parameters and observing the effect on LFP biomarkers (and potentially clinical outcomes), continuously refining its control policy over time. This promises truly autonomous and personalized therapy.

5.3 Technological Integration and Closed-Loop Systems

The seamless integration of sophisticated LFP sensing capabilities into miniaturized, implantable DBS devices represents a monumental engineering feat. The evolution from open-loop to closed-loop adaptive DBS systems epitomizes this advancement.

- Hardware Constraints: Implantable Pulse Generators (IPGs) must be compact, energy-efficient, and robust enough to function reliably within the human body for many years. Incorporating LFP sensing circuitry (low-noise amplifiers, ADCs, digital signal processors) alongside high-power stimulation circuitry within these constraints is a significant challenge. Battery life is a critical consideration; efficient power management and low-power sensing chips are essential for extending the time between battery replacements.

- Medtronic’s BrainSense™ Technology: This system exemplifies state-of-the-art technological integration (Medtronic, 2025).

- Integrated Sensing and Stimulation: The IPG (e.g., Percept™ PC) contains dedicated hardware for both delivering stimulation and continuously recording LFPs from the same implanted DBS lead.

- Data Acquisition and Storage: The BrainSense™ technology can record patient-specific LFP data, which is wirelessly transmitted to a clinician programmer or patient device. This allows for long-term monitoring of brain activity in the patient’s home environment, providing valuable insights into disease fluctuations that are difficult to capture during brief clinic visits.

- Closed-Loop Algorithm (aDBS): The core innovation is the ability to use the sensed LFP data to automatically adjust stimulation parameters. For PD, this involves monitoring beta band power. If beta power crosses a predefined threshold, stimulation is increased; if it falls below another threshold, stimulation is reduced. This creates a feedback loop: sensing brain state -> processing data -> making a decision -> adjusting stimulation -> observing effect on brain state. This intelligent control aims to maintain LFP biomarkers within a desired therapeutic range.

- Clinical Implications: The benefits are profound: reduced programming burden for clinicians, optimized symptom control throughout the day, decreased stimulation-induced side effects due to dynamic adjustments, and potentially extended battery life by stimulating only when needed.

- Future Directions: The field is rapidly evolving towards even more advanced systems:

- Multi-Region Sensing: Simultaneously recording LFPs from multiple deep brain targets or combining deep brain signals with cortical EEG to capture more comprehensive brain network dynamics.

- Multi-Modal Sensing: Integrating LFP sensing with other physiological signals (e.g., accelerometry for movement, EMG, heart rate) to provide a richer context for brain activity and enhance algorithm robustness.

- Ultra-Miniaturization and Wireless Power: Developing even smaller, leadless, wirelessly powered implantable devices.

- Advanced Control Algorithms: Implementing more sophisticated AI and learning algorithms directly within the implanted device for truly autonomous and self-optimizing therapy.

5.4 Ethical and Regulatory Considerations

As neuromodulation technologies become more sophisticated and autonomous, important ethical and regulatory questions arise.

- Data Privacy and Security: Brain activity data is highly sensitive. Ensuring its privacy, security, and responsible use is paramount, especially as systems collect long-term, real-world data.

- Autonomy and Responsibility: As aDBS systems become more autonomous, questions about agency and responsibility for therapeutic decisions will emerge. How much control should the patient or clinician have over an adaptive system’s parameters?

- Transparency and Explainability: Understanding how complex AI algorithms in aDBS make decisions is crucial for clinicians and patients. ‘Black box’ algorithms pose challenges for trust and accountability.

- Regulatory Pathways: The rapid pace of innovation necessitates agile yet rigorous regulatory frameworks to ensure the safety, efficacy, and ethical deployment of these advanced neurotechnologies.

Overcoming these challenges and harnessing these advancements will solidify the role of LFP-based adaptive neuromodulation as a transformative force in neurological care, ushering in an era of truly personalized and highly effective brain therapies.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

6. Conclusion

Local Field Potentials have emerged from the realm of basic neuroscience research to become an indispensable component in the sophisticated landscape of modern neurotherapeutics. As extracellular electrical signals representing the aggregate synaptic activity of neuronal populations, LFPs offer unparalleled insights into the dynamic interplay of neural circuits in both health and disease. Their distinct oscillatory patterns, particularly within specific frequency bands, serve as powerful and objective biomarkers for the pathophysiology of a range of debilitating neurological disorders.

The detailed understanding of LFP generation, meticulous recording techniques, and advanced analytical methods have collectively paved the way for a paradigm shift in the treatment of conditions like Parkinson’s disease, essential tremor, and dystonia. The identification of pathological beta activity in PD, tremor-related oscillations in ET, and altered synchrony in dystonia has provided the fundamental neurophysiological basis for developing highly targeted interventions.

The most profound advancement lies in the seamless integration of LFP monitoring capabilities within adaptive Deep Brain Stimulation (aDBS) systems, epitomized by Medtronic’s BrainSense™ technology. This pioneering closed-loop approach represents a significant leap towards truly personalized and responsive neuromodulation. By dynamically adjusting stimulation parameters in real-time based on a patient’s own brain activity, aDBS mitigates the limitations of traditional fixed-parameter DBS, offering enhanced therapeutic efficacy, reduced side effects, and improved energy efficiency.

While significant challenges persist, particularly in robust signal interpretation amidst noise, addressing inter-individual variability, and the complex technological integration within implantable devices, the relentless pace of research and development continues to yield groundbreaking solutions. Innovations in advanced signal processing, machine learning algorithms, and miniaturized hardware are steadily refining the understanding and application of LFPs, promising an even brighter future for neurosurgical interventions.

The journey from initial LFP discovery to its implementation in intelligent, adaptive neuromodulation systems underscores a remarkable convergence of neurophysiology, engineering, and clinical neurology. As this field continues to evolve, propelled by ongoing research and technological innovations, LFP-guided adaptive DBS is set to deliver increasingly precise, effective, and patient-centric therapies, ultimately improving the quality of life and restoring greater autonomy to countless individuals grappling with chronic neurological disorders. The ability to listen to the brain’s own language and respond in kind marks a truly transformative era in medicine.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

References

- Medtronic. (2025). Medtronic earns U.S. FDA approval for the world’s first Adaptive deep brain stimulation system for people with Parkinson’s. Retrieved from news.medtronic.com

- Medtronic. (2025). BrainSense™ Technology. Retrieved from medtronic.com

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). Local field potential. Retrieved from en.wikipedia.org

- ScienceDirect. (n.d.). Local Field Potential – an overview. Retrieved from sciencedirect.com

- PubMed. (2022). Local Field Potentials in Deep Brain Stimulation: Investigation of the Most Cited Articles. Retrieved from pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- TIME. (2025). Parkinson’s Patients Have a New Way to Manage Their Symptoms. Retrieved from time.com

Be the first to comment