Abstract

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is fundamentally reshaping the landscape of medical diagnostics, offering unparalleled advancements in the precision, efficiency, and accessibility of disease detection, characterization, and management. This comprehensive report meticulously explores the transformative potential of AI across a diverse spectrum of medical diagnostic fields, including advanced medical imaging, digital pathology, genomics, proteomics, and real-time patient monitoring. It delves into the sophisticated methodologies employed by AI, such as deep learning and natural language processing, illustrating their intricate mechanisms and impact. Crucially, the report critically examines the multifaceted challenges inherent in large-scale data acquisition, the pervasive issue of algorithmic bias, and the imperative for interpretability in clinical settings. Furthermore, it scrutinizes the evolving regulatory pathways governing AI-powered medical devices, addresses profound ethical considerations concerning diagnostic autonomy, patient privacy, and accountability, and highlights AI’s pivotal role in democratizing access to expert-level diagnostics on a global scale, particularly in underserved regions. The aim is to provide an in-depth analysis of AI’s current state, future trajectory, and its far-reaching implications for healthcare delivery.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

1. Introduction: The Dawn of Intelligent Diagnostics

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into medical diagnostics marks a pivotal moment in healthcare history, ushering in a new era characterized by unprecedented opportunities to enhance patient outcomes, optimize clinical workflows, and foster a more personalized and predictive approach to medicine. AI, as a broad interdisciplinary field, encompasses a sophisticated array of computational technologies, including machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), natural language processing (NLP), and computer vision. These technologies empower systems to meticulously analyze vast and complex medical datasets, discern subtle yet critical patterns, and subsequently generate highly informed decisions or predictions that often augment or even surpass human capabilities in specific tasks. The profound applicability of AI spans an ever-widening array of medical domains, from the precise interpretation of medical images and the meticulous analysis of pathological specimens to the deciphering of intricate genomic sequences. Each application contributes synergistically to the overarching goal of establishing a healthcare paradigm that is not only more personalized and precise but also proactive and preventive.

Historically, medical diagnostics have relied heavily on human expertise, empirical observations, and often, subjective interpretations. While invaluable, these methods can be susceptible to variability, fatigue, and the inherent limitations of processing extremely large, multi-modal datasets. The advent of digital healthcare, characterized by electronic health records (EHRs), high-resolution medical imaging, and next-generation sequencing, has generated an explosion of data, far exceeding human capacity for manual analysis. This ‘big data’ phenomenon has created fertile ground for AI, which excels at identifying correlations, anomalies, and prognostic indicators within complex data structures that would otherwise remain hidden. By automating repetitive tasks, assisting in the identification of obscure disease markers, and predicting disease progression or treatment response, AI promises to transform diagnostics from a reactive process into a proactive, data-driven science, thereby improving the speed, accuracy, and consistency of diagnoses and ultimately, the quality of patient care.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

2. AI Methodologies in Medical Diagnostics: Unpacking the Algorithms

AI’s prowess in medical diagnostics stems from its diverse arsenal of methodologies, each uniquely suited to tackling specific types of medical data and diagnostic challenges. Understanding these core methodologies is crucial to appreciating their capabilities and limitations.

2.1 Machine Learning and Deep Learning: The Analytical Powerhouses

Machine learning (ML) forms the foundational bedrock of much of modern AI in diagnostics. At its core, ML involves the development of algorithms that enable computers to learn from data without being explicitly programmed. Instead of following rigid instructions, ML models identify patterns, build predictive models, and adapt their performance based on exposure to new data. Within ML, deep learning (DL) represents a powerful subset characterized by artificial neural networks with multiple layers (hence ‘deep’). These layered architectures allow DL models to automatically learn hierarchical representations of features from raw input data, negating the need for manual feature engineering—a significant advantage in complex medical applications.

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): CNNs have emerged as the undisputed champions in the realm of medical image analysis. Inspired by the human visual cortex, CNNs are particularly adept at processing grid-like data, such as images. Their architecture typically comprises convolutional layers (which apply filters to detect features like edges, textures, and patterns), pooling layers (to reduce dimensionality and retain essential information), and fully connected layers (for classification). In diagnostics, CNNs have demonstrated exceptional performance in interpreting medical images across modalities like X-rays, CT scans, MRI, and ultrasound. For instance, sophisticated CNN architectures can accurately detect subtle intracranial hemorrhages, identify spinal fractures that might be missed by the human eye, and pinpoint pulmonary embolisms with remarkable speed and precision, significantly enhancing diagnostic accuracy and efficiency (en.wikipedia.org). Advanced CNNs are also employed for tasks such as tumor segmentation, organ delineation, and the quantification of disease burden, providing objective metrics that aid radiologists and clinicians.

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Transformers: While CNNs excel with spatial data, RNNs and their more advanced counterparts, such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Transformers, are designed to process sequential data. In diagnostics, this includes time-series data from continuous patient monitoring (e.g., vital signs, ECGs), longitudinal electronic health records, or genetic sequences. RNNs can learn dependencies across time steps, making them suitable for predicting disease trajectories, forecasting patient deterioration, or identifying patterns in symptom progression. Transformer models, with their attention mechanisms, have recently revolutionized natural language processing and are increasingly applied to diverse sequential data, including genomic sequences and structured EHR data, to identify complex interactions and predict outcomes.

- Other Machine Learning Paradigms: Beyond deep learning, other ML algorithms contribute significantly. Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and Random Forests are robust classifiers often used for structured tabular data, risk stratification, or in scenarios with smaller, well-curated datasets. Unsupervised learning techniques, such as clustering algorithms (e.g., K-means, hierarchical clustering), are invaluable for discovering hidden subgroups within patient populations or identifying novel disease phenotypes without prior labels. Reinforcement learning, though less prevalent currently, holds promise for optimizing sequential decision-making in treatment planning or dynamic patient management, where the AI agent learns optimal actions through trial and error within a simulated or real clinical environment.

2.2 Natural Language Processing (NLP): Unlocking Unstructured Data

Natural Language Processing (NLP) is the branch of AI focused on enabling computers to understand, interpret, and generate human language. In medical diagnostics, NLP serves as a critical tool for extracting meaningful and structured information from the vast repositories of unstructured clinical texts, which constitute a significant portion of medical data. These texts include physician’s notes, pathology reports, radiology reports, discharge summaries, scientific literature, and patient-reported outcomes.

Key NLP techniques applied in diagnostics include:

* Tokenization and Part-of-Speech Tagging: Breaking text into individual words or phrases and identifying their grammatical roles.

* Named Entity Recognition (NER): Identifying and classifying clinical entities such as diseases, symptoms, medications, anatomical structures, and laboratory values within text. For example, identifying ‘myocardial infarction’ as a disease or ‘aspirin’ as a medication.

* Relation Extraction: Uncovering relationships between identified entities, such as ‘drug X treats disease Y’ or ‘symptom Z is associated with condition A’.

* Sentiment Analysis: Assessing the emotional tone of patient notes or feedback, which can be indicative of patient experience or mental health status.

* Clinical Concept Extraction and Mapping: Converting free-text descriptions into standardized medical ontologies and terminologies (e.g., SNOMED CT, ICD-10), which facilitates data integration and analysis. This process allows for the systematic identification of disease markers, treatment outcomes, patient histories, and comorbidities, thereby profoundly supporting clinical decision-making, epidemiological research, and cohort identification for clinical trials.

Challenges in medical NLP include the highly specialized jargon, abbreviations, misspellings, syntactical ambiguity, and the need for robust de-identification techniques to protect patient privacy while making data usable for AI training.

2.3 Computer Vision: The Eye of AI

While often intertwined with deep learning, computer vision is a distinct field within AI that equips machines with the ability to ‘see’ and interpret visual information from the world, much like humans do. In medical diagnostics, computer vision algorithms are specifically designed to process and analyze medical images. This involves tasks such as:

* Object Detection: Identifying specific regions of interest, such as tumors, lesions, or anatomical structures, within an image.

* Image Segmentation: Delineating precise boundaries of organs, tissues, or pathologies at a pixel level, which is critical for volumetric measurements and treatment planning.

* Image Classification: Assigning a label to an entire image, for example, classifying an X-ray as ‘pneumonia present’ or ‘no pneumonia’.

* Image Registration: Aligning multiple images from different modalities or time points, crucial for tracking disease progression or fusing information.

These computer vision capabilities are fundamental to AI’s impact across medical imaging and digital pathology, enabling automated analysis that can be faster, more consistent, and sometimes more accurate than human interpretation alone.

2.4 Multimodal AI and Data Integration

An increasingly important methodology involves multimodal AI, where models are trained on diverse data types simultaneously (e.g., images, genomic data, EHR text, physiological signals). By integrating information from multiple sources, these models can develop a more holistic and robust understanding of a patient’s condition, leading to more comprehensive and accurate diagnoses and predictions. This interdisciplinary approach leverages the strengths of various AI methodologies to create a more complete ‘digital twin’ of the patient.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

3. Applications Across Medical Diagnostic Fields: A Panoramic View

AI’s influence is permeating nearly every facet of medical diagnostics, offering innovative solutions to long-standing challenges and opening new avenues for understanding and treating diseases.

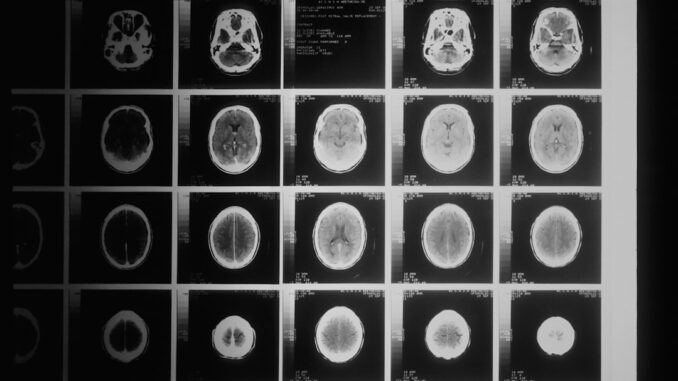

3.1 Medical Imaging: Enhancing the Radiologist’s Gaze

Medical imaging is arguably the field where AI has made the most tangible and widespread impact. AI algorithms are revolutionizing how radiologists and other specialists interpret imaging data, ranging from basic X-rays to complex MRI and CT scans. The capabilities extend beyond mere detection to precise characterization, prognostication, and treatment planning.

- Detection and Characterization: AI excels at identifying subtle anomalies that might escape human detection due to their size, location, or the sheer volume of images. For instance, in oncology, AI systems can detect lung nodules on CT scans, breast microcalcifications on mammograms, and prostate lesions on MRI with high sensitivity, often flagging suspicious areas for human review. Studies have shown AI systems to achieve superior performance in reducing false positives and negatives in mammography screenings compared to human radiologists, thereby minimizing unnecessary biopsies and improving patient experience (time.com). Beyond cancer, AI aids in detecting acute conditions like intracranial hemorrhage on head CTs, pneumothorax on chest X-rays, and acute appendicitis on abdominal CTs.

- Disease Specific Applications:

- Gastric Cancer: AI systems have been developed to detect gastric cancer invasion depth with high accuracy during endoscopy, outperforming human endoscopists by a significant margin. This precision is crucial for guiding treatment strategies, from endoscopic resection to surgical intervention (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

- Retinopathy: AI algorithms can analyze retinal images to detect early signs of diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, and macular degeneration, offering rapid screening in underserved areas where ophthalmologists are scarce.

- Dermatology: AI models, trained on vast datasets of skin lesions, demonstrate impressive accuracy in classifying various dermatological conditions, including melanoma, often matching or exceeding the diagnostic performance of expert dermatologists.

- Cardiovascular Disease: AI assists in quantifying cardiac function from echocardiograms and MRIs, detecting coronary artery disease from CT angiograms, and predicting cardiovascular events from multimodal imaging data.

- Neurological Disorders: AI aids in the early detection of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s by analyzing subtle changes in brain MRI or PET scans, and in stroke assessment for timely intervention.

- Workflow Optimization: AI tools can prioritize urgent cases by flagging critical findings, reducing radiologists’ workload, and decreasing turnaround times for reports. They also automate measurements (e.g., tumor volume tracking, organ size) and generate quantitative reports, adding objectivity and consistency.

- Image Reconstruction and Enhancement: AI can reconstruct high-quality images from limited raw data, reduce imaging artifacts, and denoise images, potentially leading to lower radiation doses or faster scan times without compromising diagnostic quality.

3.2 Pathology: Digitalizing the Microscopic World

Pathology, traditionally a manual and microscope-centric discipline, is undergoing a profound transformation with the advent of digital pathology and AI. Digital pathology involves scanning entire glass slides at high resolution to create ‘whole slide images’ (WSIs), which can then be viewed, analyzed, and shared digitally. This digital shift provides the canvas upon which AI algorithms can operate.

- Automated Analysis: AI assists pathologists in analyzing these large digital pathology images to identify disease markers, grade tumors, detect metastatic spread, and predict patient outcomes. For instance, AI algorithms can accurately segment and count specific cell types (e.g., mitotic figures, lymphocytes), quantify immunohistochemical stains (e.g., HER2, PD-L1 expression), and identify subtle morphological changes indicative of malignancy.

- Specific Applications in Oncology:

- Prostate Cancer: A landmark achievement was the FDA approval of Paige Prostate in 2021, the first AI product for digital pathology images, designed to assist pathologists in detecting and grading prostate cancer (med.umn.edu). This signifies AI’s capability to enhance diagnostic accuracy and efficiency in complex cancer diagnoses.

- Breast Cancer: AI can aid in detecting micrometastases in lymph nodes, grading breast cancer, and predicting recurrence based on histopathological features.

- Immunohistochemistry Interpretation: AI can precisely quantify protein expression levels from stained slides, which is crucial for therapeutic decision-making.

- Workflow and Quality Control: AI systems can flag regions of interest for pathologists to review, prioritize complex cases, and perform quality control checks, reducing inter-observer variability and improving diagnostic consistency. They also facilitate remote consultations and collaborative diagnostics.

3.3 Genomics and Proteomics: Unlocking the Molecular Blueprint

AI plays an increasingly critical role in deciphering the vast and intricate data generated by genomics (study of genes) and proteomics (study of proteins). These fields are central to personalized medicine, aiming to tailor treatments based on an individual’s unique molecular profile.

- Genomic Data Analysis: AI algorithms are adept at analyzing massive amounts of genomic sequencing data (e.g., whole-genome sequencing, whole-exome sequencing, RNA sequencing) to identify genetic mutations, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), copy number variations, and gene expression changes. This analysis helps in:

- Disease Susceptibility Prediction: Identifying genetic predispositions to common and rare diseases.

- Rare Disease Diagnosis: Pinpointing causative genetic variants in patients with undiagnosed rare diseases, often by comparing patient genomes to large reference databases and known disease-associated genes.

- Pharmacogenomics: Predicting individual responses to specific drugs based on genetic makeup, optimizing drug selection and dosage, and minimizing adverse effects.

- Oncology: Identifying somatic mutations in tumor DNA that drive cancer growth, guiding targeted therapy selection, and monitoring treatment resistance.

- Proteomic Data Analysis: AI helps analyze complex proteomic datasets (e.g., mass spectrometry data) to identify specific proteins, protein isoforms, or post-translational modifications associated with disease states. This is crucial for discovering novel biomarkers for early disease detection, prognostication, and monitoring therapeutic response.

- Multi-omics Integration: A powerful application involves AI integrating data from genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and even microbiomics. By analyzing these multi-omics datasets together, AI can uncover complex biological pathways and interactions that contribute to disease, providing a more comprehensive understanding of an individual’s health and enabling highly personalized diagnostic and therapeutic strategies (en.wikipedia.org).

3.4 Wearables, Remote Monitoring, and Point-of-Care Diagnostics

AI’s diagnostic capabilities are extending beyond traditional clinical settings into everyday life through wearables and remote monitoring devices. These devices continuously collect physiological data, which AI can analyze in real-time to detect subtle changes indicative of impending health issues.

- Continuous Monitoring: Smartwatches, fitness trackers, and specialized medical sensors can monitor heart rate, heart rate variability, sleep patterns, activity levels, blood oxygen saturation, and even ECG. AI algorithms analyze this continuous stream of data to detect anomalies suggestive of cardiac arrhythmias (e.g., atrial fibrillation), sleep apnea, or early signs of infection. This enables proactive intervention and chronic disease management.

- Point-of-Care Diagnostics (POCD): AI is being integrated into portable, low-cost diagnostic devices for use in homes, clinics, or remote settings. For example, AI-powered smartphone applications can analyze images of skin lesions, assess wound healing, or even interpret rapid diagnostic tests, making expert-level diagnostics more accessible without the need for specialized laboratory equipment.

- Early Disease Detection: By continuously monitoring health parameters, AI can identify patterns that precede the onset of symptoms, enabling earlier diagnosis and intervention for conditions like diabetes, hypertension, or even mental health disorders, facilitating truly preventive healthcare.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

4. Challenges in Data Acquisition, Bias, and Interpretability

Despite AI’s immense promise, its effective and ethical deployment in medical diagnostics is hindered by several significant challenges related to data, fairness, and transparency.

4.1 Data Quality, Availability, and Interoperability

The effectiveness, robustness, and generalizability of any AI model are fundamentally contingent upon the quality, quantity, and representativeness of its training data. In medical diagnostics, acquiring such ideal datasets presents considerable obstacles.

- Data Scarcity for Rare Conditions: While abundant data exists for common diseases, rare diseases often suffer from a scarcity of labeled examples, making it difficult to train robust AI models. This often necessitates techniques like transfer learning, data augmentation, or synthetic data generation, each with its own limitations.

- Annotation Burden and Expert Dependency: Medical data, especially images and pathology slides, requires meticulous, time-consuming, and expensive annotation by highly skilled domain experts (e.g., radiologists, pathologists). The subjectivity inherent in human annotation can also introduce variability and noise into datasets.

- Data Fragmentation and Silos: Healthcare data is often fragmented across different institutions, departments, and proprietary systems. A lack of standardized data formats and interoperability protocols (e.g., inconsistent EHR systems, varied DICOM standards for imaging) makes it challenging to aggregate large, diverse datasets necessary for training generalizable AI models. This issue is particularly acute in federated learning scenarios where models are trained locally and only aggregated parameters are shared.

- Privacy and Security Concerns: Medical data is highly sensitive. Strict regulations (e.g., HIPAA in the US, GDPR in Europe) govern its collection, storage, and sharing. De-identification and anonymization techniques are crucial but imperfect, and the risk of re-identification or data breaches remains a significant concern, often limiting data sharing and model development.

- Ethical Data Sourcing: Ensuring that data is collected with proper informed consent and ethical oversight is paramount. The use of data from vulnerable populations or without explicit consent raises serious ethical dilemmas.

4.2 Bias and Fairness: The Imperative for Equitable Diagnostics

AI models are powerful pattern recognizers, but they are not inherently neutral. They learn from the data they are fed, and if that data reflects historical biases, the AI model will inevitably perpetuate and even amplify those biases, leading to disparities in diagnostic accuracy and healthcare outcomes across different patient populations.

- Sources of Bias:

- Selection Bias: Training datasets may disproportionately represent certain demographic groups (e.g., predominantly male, white patients), leading to poorer performance when applied to underrepresented groups (e.g., women, ethnic minorities). For example, AI models trained on primarily light skin tones may perform poorly in detecting skin cancer in individuals with darker skin tones.

- Algorithmic Bias: Flaws in algorithm design or optimization choices can inadvertently lead to biased outcomes, even with unbiased data.

- Measurement Bias: Inconsistent or biased data labeling by human annotators can introduce bias. For instance, if certain symptoms are historically underdiagnosed in a specific population, the AI will learn to similarly underdiagnose them.

- Consequences of Bias: Biased AI can lead to misdiagnosis, delayed diagnosis, or inappropriate treatment recommendations for specific patient groups, exacerbating existing health inequities and eroding trust in AI technology.

- Mitigation Strategies: Addressing bias requires a multi-pronged approach:

- Diverse and Representative Datasets: Actively curating datasets that reflect the demographic diversity of the target population.

- Algorithmic Transparency and Fairness Metrics: Developing and employing metrics to quantify fairness across different subgroups and designing algorithms that explicitly minimize bias.

- Debiasing Techniques: Applying statistical or algorithmic methods to reduce bias in training data or model predictions.

- Continuous Monitoring and Validation: Regularly auditing AI models in real-world settings to detect and rectify emergent biases.

- Ethical AI Design: Integrating ethical considerations from the initial stages of data collection and model development.

4.3 Interpretability and Explainability (XAI): Opening the Black Box

Many powerful AI models, particularly deep learning networks, operate as ‘black boxes,’ meaning their decision-making processes are opaque and difficult for humans to understand. In medical diagnostics, where trust, accountability, and clinical reasoning are paramount, this lack of transparency poses a significant challenge.

- The ‘Black Box’ Problem: Clinicians need to understand why an AI model made a particular diagnosis or prediction to trust its output, validate its reasoning, and take legal or ethical responsibility. If an AI suggests a diagnosis, a clinician needs to be able to confirm that the AI’s reasoning aligns with medical understanding and patient context.

- Consequences of Lack of Interpretability: Without interpretability, it is difficult to:

- Identify and correct errors or biases in the AI’s reasoning.

- Build trust among healthcare professionals and patients.

- Justify clinical decisions based on AI outputs.

- Learn new medical insights from the AI’s findings.

- Meet regulatory requirements for transparency.

- Explainable AI (XAI) Techniques: Researchers are developing XAI methods to make AI models more transparent:

- Post-hoc Explanations: Techniques like LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) and SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) provide local explanations by identifying which input features were most influential in a specific prediction.

- Attention Mechanisms: In neural networks, attention maps can highlight the regions of an image or parts of text that the model focused on when making a decision.

- Simpler Models and Rule-Based Systems: For certain tasks, using more inherently interpretable models or integrating rule-based systems can offer clearer insights, though often at the cost of some predictive power.

The push for XAI is driven by the need to integrate AI seamlessly and responsibly into clinical practice, ensuring that AI serves as a trusted assistant rather than an unscrutinized oracle.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

5. Regulatory Pathways for AI-Powered Devices: Ensuring Safety and Efficacy

The rapid evolution of AI in medical diagnostics necessitates robust and adaptable regulatory frameworks to ensure the safety, efficacy, and ethical deployment of AI-powered medical devices. Traditional regulatory approaches, designed for static medical devices, often struggle to accommodate the dynamic, learning nature of AI/ML algorithms.

- Evolving Regulatory Landscape: Regulatory bodies worldwide, such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and others, are actively developing specific guidelines for Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning-based Software as a Medical Device (AI/ML SaMD).

- Software as a Medical Device (SaMD): Many AI diagnostic tools fall under the classification of SaMD, which refers to software intended to be used for one or more medical purposes without being part of a hardware medical device. Regulators categorize SaMD based on risk, with higher-risk devices requiring more rigorous pre-market and post-market oversight.

- Key Regulatory Considerations:

- Algorithm Validation: Rigorous testing and validation of the AI algorithm’s performance on independent, diverse datasets are required to demonstrate accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity. This often involves extensive clinical trials.

- Clinical Performance: Beyond technical performance, regulators demand evidence of real-world clinical utility and patient benefit.

- Data Management: Scrutiny extends to the quality of training data, data curation processes, and measures taken to address potential biases.

- Transparency and Explainability: While not always explicitly mandated, there’s growing pressure for AI products to offer a degree of interpretability to clinicians.

- Post-Market Surveillance and Real-World Evidence (RWE): A critical aspect for AI/ML SaMD, especially for ‘adaptive’ or ‘continuously learning’ algorithms. Regulators are developing frameworks to monitor performance in real-world use, track adverse events, and manage algorithm modifications. The FDA’s ‘Predetermined Change Control Plan’ aims to allow for safe modifications to algorithms within predefined limits without requiring full re-approval for every minor update.

- Specific Examples:

- The FDA’s approval of Paige Prostate in 2021 marked a significant milestone, being the first AI product for digital pathology images to receive such clearance (med.umn.edu). This demonstrated a pathway for sophisticated AI algorithms to enter clinical practice.

- The FDA released its ‘Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML) Based Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) Action Plan’ in 2021, outlining its strategy for regulating these dynamic technologies, focusing on good machine learning practice, transparency, and a patient-centered approach.

The regulatory environment for AI in diagnostics is dynamic and complex, balancing the need to foster innovation with the paramount responsibility of protecting patient safety and ensuring public trust. Collaborative efforts between industry, academia, and regulatory bodies are crucial to establishing clear, predictable, and robust pathways for AI innovation in healthcare.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

6. Ethical Considerations: Navigating the Moral Landscape of AI Diagnostics

The integration of AI into medical diagnostics introduces a complex array of ethical considerations that demand careful scrutiny and proactive mitigation strategies. These issues extend beyond technical performance to touch upon core principles of medical ethics, patient rights, and societal equity.

6.1 Diagnostic Autonomy, Accountability, and the Human-AI Partnership

The deployment of AI in diagnostics fundamentally alters the traditional diagnostic workflow and raises critical questions about the roles of healthcare professionals and AI systems.

- Maintaining Human Oversight: While AI can augment diagnostic capabilities, it is imperative to maintain human oversight. AI should function as an intelligent assistant or decision support tool, not a replacement for human clinicians. The final diagnostic decision, especially for complex or ambiguous cases, must remain with a qualified human professional who can integrate AI insights with their clinical judgment, patient context, and ethical considerations.

- Accountability for Errors: A significant ethical and legal challenge is determining accountability when an AI-assisted diagnosis leads to an adverse patient outcome. Is the developer of the AI model responsible? The clinician who used the AI? The institution that deployed it? Clear frameworks for liability are needed to ensure patient safety and instill confidence in AI tools. This also relates to the ‘black box’ problem, as accountability is difficult if the reasoning is opaque.

- Erosion of Clinical Skills: Over-reliance on AI could potentially lead to a deskilling of healthcare professionals, particularly trainees. It is crucial to ensure that AI tools complement rather than supplant the development of fundamental diagnostic competencies.

- The Human-in-the-Loop: Designing AI systems with a ‘human-in-the-loop’ approach is paramount. This ensures that clinicians can critically review AI outputs, override recommendations when appropriate, and provide feedback that can help refine the AI’s performance.

6.2 Informed Consent and Patient Understanding

The use of AI in diagnostics necessitates transparent and comprehensive communication with patients regarding how their data will be utilized, the role of AI in their care pathway, and the potential implications for their health outcomes.

- Granular Consent: Patients should provide informed consent not just for medical procedures but also for the use of their data for AI training and the application of AI in their diagnosis. This consent should be granular, specifying how their data might be used (e.g., for research, for commercial development, for clinical decision support).

- Clear Communication: Explaining AI’s role to patients in understandable, non-technical language is crucial. Patients need to comprehend that AI is a tool, not an infallible entity, and that human oversight remains central. Managing patient expectations about AI’s capabilities and limitations is key to maintaining trust.

- Right to Know and to Refuse: Patients should have the right to know if AI is being used in their diagnostic process and, where feasible and clinically appropriate, to refuse its use or request a human-only diagnosis.

6.3 Privacy and Data Security

Medical data is among the most sensitive personal information. The use of AI, which often requires large datasets, amplifies existing concerns about privacy and data security.

- Data Protection Regulations: Strict adherence to data protection regulations like GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) in Europe, HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) in the U.S., and similar laws globally is non-negotiable. This involves robust anonymization, pseudonymization, and de-identification techniques to protect patient identities.

- Cybersecurity Risks: AI systems, like any digital technology, are vulnerable to cyberattacks. Data breaches in healthcare AI systems could expose highly sensitive personal and medical information, leading to severe consequences for individuals and institutions.

- Algorithmic Transparency and Data Provenance: Understanding the lineage of data used to train AI models and ensuring its ethical sourcing is vital. Transparency about data handling practices helps build public trust.

- Federated Learning: This emerging AI paradigm offers a potential solution by allowing models to be trained on decentralized datasets without the data ever leaving its source, thus enhancing privacy and security.

6.4 Equity and Access: Bridging or Widening Divides?

While AI holds immense promise for democratizing access to diagnostics, it also carries the risk of exacerbating existing health disparities if not carefully managed.

- Exacerbating Disparities: If AI models are trained on biased data (e.g., predominantly from affluent populations), they may perform poorly or generate biased recommendations for underserved communities, further widening health equity gaps.

- Cost and Infrastructure: The high cost of developing, deploying, and maintaining advanced AI systems, coupled with the need for robust digital infrastructure, could limit access to these technologies in low-resource settings, creating a ‘digital divide’ in healthcare.

- Mitigation: Proactive measures to ensure equitable access include developing AI for low-cost platforms (e.g., smartphones), prioritizing deployment in underserved areas, and ensuring that datasets used for training are diverse and representative of global populations.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

7. Democratizing Access to Diagnostics: AI as an Equalizer

One of the most compelling potentials of AI in medical diagnostics lies in its ability to democratize access to expert-level healthcare, particularly in regions burdened by a scarcity of specialists, limited infrastructure, or geographical isolation. By transforming complex diagnostic processes into more accessible, efficient, and cost-effective tools, AI can significantly bridge existing gaps in healthcare equity and quality.

- Overcoming Geographical Barriers: In rural or remote areas where access to specialist physicians (e.g., radiologists, pathologists, ophthalmologists) is severely limited, AI systems can provide frontline diagnostic support. For example, AI-powered retinal scanners can detect diabetic retinopathy in primary care settings or mobile clinics, obviating the need for patients to travel long distances to see an ophthalmologist. Similarly, AI can assist in the interpretation of chest X-rays for tuberculosis screening in remote communities, enabling earlier detection and treatment in endemic regions.

- Addressing Specialist Shortages: Many countries face critical shortages of medical specialists. AI can act as a force multiplier, augmenting the capabilities of existing healthcare providers, including general practitioners, nurses, and community health workers. By automating preliminary screening, flagging suspicious cases, or providing decision support, AI allows specialists to focus their expertise on the most complex cases, thereby optimizing the utilization of limited human resources.

- Reducing Costs and Increasing Efficiency: The automation of diagnostic tasks by AI can significantly reduce the operational costs associated with manual review, specialist consultations, and protracted diagnostic pathways. Faster and more accurate diagnoses can also lead to more timely and effective treatments, reducing the burden of disease and long-term healthcare expenditures. For instance, the high accuracy of AI in detecting gastric cancer invasion depth, surpassing human endoscopists, means more efficient and precise treatment planning, potentially avoiding unnecessary surgeries or improving outcomes (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

- Point-of-Care and Mobile Diagnostics: AI integration into portable devices, such as smartphone apps or compact diagnostic tools, enables sophisticated analyses to be performed at the point of care, outside traditional hospital settings. This is particularly impactful for infectious disease screening, basic imaging interpretation, or chronic disease monitoring in community clinics or even patients’ homes. These solutions empower local healthcare providers with capabilities previously restricted to specialized centers.

- Standardizing Care Quality: AI, when properly validated and deployed, can reduce diagnostic variability inherent in human interpretation. By providing consistent, evidence-based assessments, AI can help standardize the quality of care across different regions and socioeconomic strata, ensuring that patients receive a comparable level of diagnostic accuracy regardless of where they access healthcare.

- Empowering Patients: With the advent of consumer-grade wearables and AI-powered health apps, individuals are increasingly empowered to monitor their own health data and receive early warnings about potential issues. While these tools require careful clinical validation and oversight, they represent a shift towards proactive patient engagement and self-management, contributing to preventative care.

By leveraging AI to overcome resource constraints and geographical disparities, the global healthcare community can make significant strides towards achieving universal health coverage and ensuring that high-quality, precise diagnostics are accessible to everyone, everywhere.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

8. Conclusion and Future Directions

Artificial Intelligence is unequivocally poised to catalyze a profound and lasting transformation in medical diagnostics, enhancing the precision, efficiency, and accessibility of healthcare services across the globe. From revolutionizing the interpretation of complex medical images and digitizing pathology workflows to unraveling the intricacies of genomic data and facilitating real-time patient monitoring, AI’s capabilities are continually expanding, promising a future of more personalized, predictive, and preventive medicine.

However, the path forward is not without its formidable challenges. Critical issues such as ensuring the quality, diversity, and availability of training data, mitigating inherent algorithmic biases to guarantee equitable outcomes, developing truly interpretable AI models, and navigating complex ethical and regulatory landscapes remain paramount. Addressing these multifaceted hurdles will require sustained interdisciplinary research, robust policy development, and collaborative efforts among clinicians, researchers, engineers, ethicists, and policymakers.

Looking to the future, several exciting directions are emerging:

- Multimodal and Integrated AI: The development of AI models that can seamlessly integrate and analyze diverse data types—from imaging and genomics to clinical notes and physiological sensors—will provide a more holistic understanding of disease, paving the way for advanced digital twins of patients.

- Federated Learning and Privacy-Preserving AI: To overcome data privacy concerns and fragmentation, federated learning approaches will enable AI model training across decentralized datasets without centralizing sensitive patient information.

- Causal AI and Explainable Predictive Models: Beyond correlation, future AI will increasingly focus on inferring causality in disease mechanisms and treatment responses, offering deeper biological insights and more trustworthy predictions. Advances in Explainable AI (XAI) will make these models more transparent and clinically actionable.

- AI for Proactive and Preventive Health: AI integrated with wearables and continuous monitoring devices will shift diagnostics from reactive detection to proactive risk assessment and early intervention, moving towards a truly preventive healthcare paradigm.

- AI-Driven Drug Discovery and Repurposing: AI will accelerate the identification of novel drug targets, optimize drug design, and facilitate the repurposing of existing drugs for new indications, directly impacting diagnostic and therapeutic pipelines.

- AI in Surgical Robotics and Interventional Diagnostics: The integration of AI with robotics will enhance precision in biopsy procedures, minimally invasive surgery, and image-guided interventions, improving diagnostic yield and therapeutic outcomes.

The future of AI in medical diagnostics holds immense promise for delivering truly personalized medicine, significantly improving patient outcomes, and fostering a more equitable and efficient healthcare system. By conscientiously addressing the challenges and strategically investing in innovation, humanity stands on the cusp of a diagnostic revolution that will redefine healthcare for generations to come.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

References

- en.wikipedia.org. (n.d.). Aidoc. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aidoc

- time.com. (n.d.). Mammograms Google AI. Retrieved from https://time.com/6237088/mammograms-google-ai/

- med.umn.edu. (n.d.). Turner Foresees Bright Future as Field Goes Digital. Retrieved from https://med.umn.edu/pathology/news/turner-foresees-bright-future-field-goes-digital

- en.wikipedia.org. (n.d.). Artificial intelligence in healthcare. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_intelligence_in_healthcare

- pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. (n.d.). AI system for gastric cancer invasion depth. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40283208/

Be the first to comment