Deep Learning in Medical Imaging: Advancing Diagnostics, Overcoming Challenges, and Navigating Ethical Imperatives

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

Abstract

Deep learning, a highly specialized subset of artificial intelligence, has profoundly transformed the landscape of medical imaging, offering unprecedented capabilities to enhance diagnostic accuracy, streamline treatment planning, and ultimately improve patient outcomes. This comprehensive report meticulously explores the multifaceted applications of deep learning across various domains within medical imaging, with a particular focus on its pivotal roles in advanced image segmentation, sophisticated image reconstruction, and the synergistic analysis of multimodal imaging data. Beyond the technological advancements, the report critically examines the significant practical and conceptual challenges inherent in implementing deep learning models within diverse clinical settings. These challenges encompass critical issues such as safeguarding data privacy and security, mitigating inherent algorithmic biases that can perpetuate or exacerbate health disparities, and addressing the persistent demand for greater interpretability and transparency in model decision-making processes. Furthermore, the report delves into the crucial ethical considerations that underpin the responsible deployment of deep learning in healthcare, including the imperative of robust informed consent, the establishment of clear accountability frameworks, and the unwavering commitment to ensuring fairness and equity. By addressing these technical, practical, and ethical dimensions, this report aims to provide a holistic and nuanced understanding of the transformative potential and the complex responsibilities associated with integrating deep learning into modern medical practice.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

1. Introduction

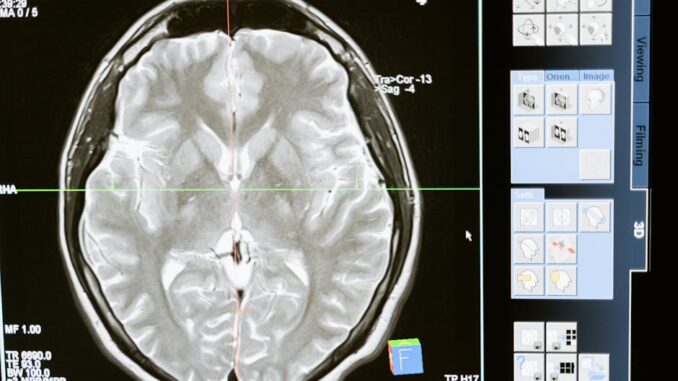

Medical imaging stands as an indispensable cornerstone of contemporary healthcare, furnishing clinicians with critical visual insights essential for the precise diagnosis, staging, and monitoring of a vast spectrum of medical conditions. From the early days of X-rays to today’s sophisticated computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), and ultrasound, these technologies have continually evolved, pushing the boundaries of non-invasive diagnostics. The sheer volume and complexity of the data generated by these modalities, however, present significant challenges for human interpretation, often requiring specialized expertise and considerable time. In recent years, the advent and rapid maturation of deep learning, a powerful branch of machine learning inspired by the structure and function of the human brain’s neural networks, has ushered in a new era for medical imaging. This technological paradigm shift offers sophisticated tools capable of analyzing intricate imaging data with an accuracy and efficiency that was previously unattainable, fundamentally redefining the capabilities of computer-aided diagnosis and analysis.

Deep learning models, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), and more recently, transformer architectures, have demonstrated exceptional prowess in a diverse array of tasks. These include the precise delineation of anatomical structures and pathological findings (image segmentation), the enhancement and restoration of raw image data (image reconstruction), the intelligent categorization of images for disease detection (image classification), and the synergistic integration of information from disparate imaging modalities (multimodal image analysis). The inherent ability of deep learning models to automatically learn hierarchical features from vast datasets, often surpassing traditional image processing techniques, positions them as transformative agents in clinical diagnostics, personalized treatment planning, and prognostic assessment.

However, the seamless and responsible integration of these highly advanced computational models into routine clinical practice is not without its formidable challenges and profound ethical considerations. While the promise of improved diagnostic accuracy and streamlined workflows is immense, the practical deployment of deep learning tools demands meticulous attention to critical issues. These include, but are not limited to, ensuring the inviolability of patient data privacy and robust security measures, systematically identifying and mitigating algorithmic biases that could compromise equitable healthcare delivery, and developing models that are transparent and interpretable to foster trust among clinicians and patients alike. Furthermore, ethical frameworks concerning informed consent, accountability for AI-driven decisions, and the overarching principle of fairness must be rigorously addressed to ensure that deep learning technologies serve humanity justly and beneficently. This report endeavors to provide a comprehensive exploration of these intertwined technical advancements, implementation hurdles, and ethical imperatives, offering a holistic perspective on the evolving role of deep learning in shaping the future of medical imaging.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

2. Applications of Deep Learning in Medical Imaging

Deep learning has permeated numerous facets of medical imaging, offering innovative solutions that augment human capabilities, accelerate processes, and improve the precision of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. The core strength of deep learning lies in its ability to automatically learn complex patterns and representations directly from raw data, bypassing the need for handcrafted features that often limit traditional image processing algorithms.

2.1 Image Segmentation

Image segmentation, a foundational task in medical image analysis, involves the precise partitioning of an image into multiple, distinct regions, each corresponding to an anatomical structure, a pathological finding, or a specific tissue type. Accurate segmentation is crucial for volumetric analysis, surgical planning, radiation therapy dose calculation, and monitoring disease progression. Historically, manual segmentation has been time-consuming, subjective, and prone to inter-observer variability, while traditional algorithmic approaches often struggled with complex anatomical variations and noisy image data.

Deep learning has revolutionized image segmentation by introducing architectures capable of learning highly complex, context-aware features. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are particularly well-suited for this task due to their ability to process grid-like data such as images. Architectures like the U-Net, introduced by Ronneberger et al. in 2015, have become ubiquitous in medical image segmentation. The U-Net’s characteristic ‘U’ shape combines a contracting path (encoder) that captures context and a symmetric expanding path (decoder) that enables precise localization. Skip connections between corresponding layers in the encoder and decoder paths facilitate the propagation of fine-grained details, leading to highly accurate pixel-wise classifications.

Specific Applications and Examples:

- Brain Tumor Detection and Delineation: CNNs, including advanced U-Net variants, have been extensively employed to segment brain tumors (gliomas, meningiomas) from multi-sequence magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, such as T1-weighted, T1-weighted with contrast enhancement (T1Gd), T2-weighted, and Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR) images. These models can delineate different sub-regions of a tumor (e.g., enhancing tumor, necrotic core, edema) with high accuracy, assisting neurosurgeons in pre-operative planning and oncologists in assessing treatment response. For instance, studies have shown deep learning models achieving Dice scores exceeding 0.85 for whole tumor segmentation in the BraTS (Brain Tumor Segmentation) challenges, significantly outperforming many traditional methods (ajesjournal.org).

- Organ Segmentation: Accurate segmentation of organs at risk (OARs) and target volumes in radiation therapy planning is critical. Deep learning models can rapidly and consistently segment structures like the heart, lungs, kidneys, liver, and spinal cord from CT scans, reducing the manual contouring burden and improving dose conformity. This has a direct impact on reducing side effects for patients undergoing radiotherapy.

- Lesion Detection: Beyond tumors, deep learning models are proficient in segmenting various lesions, such as breast lesions in mammograms or MRI, lung nodules in CT scans, polyps in colonoscopies, and retinal lesions (e.g., exudates, hemorrhages) in fundus images for diabetic retinopathy screening. This automates preliminary screening, identifies subtle findings, and helps prioritize cases for expert review.

- Vascular Segmentation: Delineating blood vessels from angiographic images (CT angiography, MR angiography) is vital for diagnosing vascular diseases like aneurysms, stenosis, and arteriovenous malformations. Deep learning can segment complex vascular trees, enabling precise measurements and visualization.

- Cardiac Segmentation: For cardiovascular disease assessment, deep learning models are used to segment cardiac chambers (atria, ventricles) and major vessels from cardiac MRI or CT, allowing for automated calculation of ejection fraction, myocardial mass, and other functional parameters.

Evaluation Metrics: The performance of segmentation models is typically quantified using metrics such as:

* Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC): Measures the overlap between the predicted segmentation and the ground truth, ranging from 0 (no overlap) to 1 (perfect overlap).

* Jaccard Index (IoU – Intersection over Union): Similar to Dice, but penalizes false positives more heavily.

* Hausdorff Distance: Measures the maximum distance between points on the boundaries of the predicted and ground truth segmentations, sensitive to outliers.

2.2 Image Reconstruction

Image reconstruction is the process of generating clinically meaningful images from raw data acquired by imaging modalities. This is particularly challenging in techniques like CT, MRI, PET, and SPECT, where raw measurements are often indirect and noisy. Deep learning has emerged as a powerful paradigm to address limitations in conventional reconstruction algorithms, which often involve iterative optimization or filtered back-projection methods that can be computationally intensive, prone to noise, or sensitive to artifacts.

Deep learning models can learn complex non-linear mappings from raw acquisition data to high-quality images, or from noisy/incomplete images to denoised/complete ones. This capability leads to several key advantages:

- Noise Reduction: Low-dose CT scans, for example, acquire less radiation to minimize patient exposure but result in noisier images. Deep learning models can effectively denoise these images while preserving critical anatomical details, thereby enabling lower radiation doses without compromising diagnostic quality. Autoencoders, particularly denoising autoencoders, are frequently employed for this task, learning to reconstruct clean images from noisy inputs.

- Artifact Correction: Medical images are susceptible to various artifacts (e.g., metal artifacts in CT, motion artifacts in MRI, partial volume effects in PET). Deep learning can learn to identify and correct these artifacts. For instance, models can be trained on paired datasets of artifact-corrupted and artifact-free images to learn a mapping that removes the unwanted distortions. This significantly improves image interpretability, especially in regions affected by surgical implants or patient movement.

- Accelerated Acquisition and Compressed Sensing: MRI acquisition can be time-consuming, leading to patient discomfort and motion artifacts. Deep learning allows for significant acceleration by enabling image reconstruction from undersampled k-space data (the raw data acquired in MRI). By learning to fill in the missing data or directly reconstruct images from sparse measurements, deep learning facilitates faster scans, which is beneficial for dynamic studies or uncooperative patients. Techniques rooted in compressed sensing theory combined with deep neural networks have shown remarkable success in this area (en.wikipedia.org).

- Super-Resolution: Deep learning can enhance the spatial resolution of medical images, generating high-resolution images from lower-resolution inputs. This is particularly useful in modalities where acquiring inherently high-resolution data is challenging or expensive, allowing for the visualization of finer details previously obscured.

Mechanisms and Architectures:

* Learned Iterative Reconstruction: Instead of replacing traditional iterative reconstruction entirely, deep learning can be integrated into the iterative loop to learn optimal regularization parameters or improve image priors, leading to faster convergence and better image quality.

* End-to-End Deep Reconstruction: Some approaches directly map raw sensor data to reconstructed images using large CNNs, effectively learning the entire reconstruction process. This often involves specialized loss functions that consider both image domain and measurement domain errors.

* Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs): GANs can generate realistic images from incomplete or noisy data, making them powerful for tasks like denoising, super-resolution, and even synthetic data generation for training other models.

2.3 Multimodal Image Analysis

Medical conditions often manifest differently across various imaging modalities, each offering unique physiological or anatomical insights. For instance, MRI excels in soft tissue contrast, CT is superior for bone and lung details, and PET provides functional metabolic information. Integrating data from multiple modalities can provide a more comprehensive and synergistic understanding of a patient’s condition than any single modality alone, leading to improved diagnostic accuracy, more precise staging, and better-informed treatment planning.

Deep learning models are exceptionally adept at handling and fusing heterogeneous data sources. They can learn to extract relevant features from each modality and combine them in an intelligent manner to leverage their complementary strengths. The challenge lies in aligning these images (image registration), handling differing resolutions and contrasts, and effectively combining the information content.

Fusion Strategies:

- Early Fusion (Feature-Level Fusion): This approach concatenates the raw image data or early-stage features extracted from each modality and feeds them into a single deep learning model. The model then learns to extract joint features from the combined input. This strategy requires precise image registration beforehand.

- Late Fusion (Decision-Level Fusion): In this method, separate deep learning models process each modality independently, generating modality-specific predictions or feature representations. A final decision is then made by combining these individual outputs through techniques like voting, weighted averaging, or another smaller neural network.

- Intermediate Fusion (Hybrid Fusion): This strategy involves processing each modality with initial deep learning layers, extracting intermediate-level features, and then fusing these features at a later stage within the network before generating a final output. This allows for both modality-specific feature learning and cross-modal interaction.

Specific Applications and Examples:

- Oncology: In cancer diagnosis and staging, combining anatomical imaging (CT, MRI) with functional imaging (PET) is standard. For example, PET-CT scans are widely used to identify metabolically active tumors and metastases. Deep learning models can fuse PET and CT data to improve tumor detection, boundary delineation, and prediction of treatment response, by leveraging CT’s anatomical context for precise localization of PET’s metabolic hotspots. Similar fusion is done with MRI for brain tumors, where T1, T2, FLAIR, and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequences are inherently multimodal within the MRI modality itself.

- Neurology: For neurological disorders like Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, or stroke, combining structural MRI (anatomical detail) with functional MRI (fMRI – brain activity), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI – white matter tracts), or PET (metabolic activity) offers a holistic view. Deep learning can identify subtle patterns across these modalities to aid in early diagnosis, predict disease progression, and localize epileptic foci (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34722958/).

- Cardiology: Combining cardiac MRI (CMR) for structural and functional assessment with CT angiography (CTA) for coronary artery visualization can provide a more comprehensive picture of cardiovascular health. Deep learning models can integrate these datasets to assess myocardial viability, quantify ischemia, and detect plaque rupture risk.

- Histopathology and Radiology Fusion: Emerging research explores fusing microscopic histopathological images with macroscopic radiological images. This can help correlate cellular-level changes with whole-organ imaging features, potentially improving cancer grading and prognosis, and facilitating virtual biopsies.

The ability of deep learning to learn complex cross-modal relationships automatically makes it an indispensable tool for maximizing the diagnostic yield from diverse medical imaging sources, leading to more robust and accurate clinical decision support systems.

2.4 Image Classification and Detection

Beyond segmentation, deep learning models, particularly CNNs, excel at image classification and object detection tasks. Image classification involves assigning a label (e.g., ‘normal’, ‘pneumonia’, ‘malignant’) to an entire image, while object detection involves localizing specific objects within an image using bounding boxes and classifying them. These applications are foundational for automated disease screening and preliminary diagnostic assistance.

Specific Applications:

- Disease Screening: Deep learning models can classify X-ray images to detect pneumonia, tuberculosis, or lung abnormalities with high sensitivity and specificity, often matching or exceeding radiologist performance in specific contexts. This is particularly valuable in resource-constrained settings or for rapid triaging.

- Diabetic Retinopathy Detection: Fundus photography analysis using CNNs can accurately detect signs of diabetic retinopathy, a leading cause of blindness, enabling early intervention. Models can grade the severity of retinopathy, identifying microaneurysms, hemorrhages, and exudates.

- Dermatology: Classification of skin lesions from dermatoscopic images into benign or malignant categories (e.g., melanoma detection) has shown impressive results, aiding dermatologists in triaging suspicious moles.

- Pathology: In digital pathology, deep learning models classify tissue sections for cancer diagnosis, grading, and subtype identification, reducing manual review time and improving consistency.

2.5 Prognosis and Treatment Planning

Deep learning extends beyond diagnosis to predicting disease progression and personalizing treatment strategies. By analyzing imaging data in conjunction with clinical, genomic, and proteomic data, models can identify biomarkers and predict patient response to therapies.

Specific Applications:

- Cancer Prognosis: Deep learning can predict overall survival or recurrence risk in cancer patients by analyzing tumor characteristics from imaging (radiomics) and integrating them with clinical data. This helps clinicians tailor treatment intensity and follow-up schedules.

- Treatment Response Prediction: Models can predict how a patient will respond to chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy based on pre-treatment scans and early response assessment. This allows for adaptive treatment planning and avoidance of ineffective therapies.

- Radiation Therapy Planning: Deep learning can automate and optimize the complex process of radiation dose distribution, ensuring maximum dose to the tumor while minimizing exposure to healthy tissues, often faster and more consistently than manual planning.

- Surgical Guidance: Real-time analysis of intraoperative images (e.g., ultrasound, endoscopy) using deep learning can guide surgeons, identify critical structures, or delineate tumor margins during complex procedures.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

3. Challenges in Implementing Deep Learning in Medical Imaging

Despite the remarkable advancements and vast potential of deep learning in medical imaging, its widespread and ethical integration into clinical practice is hindered by several significant challenges. These issues span technical, practical, and societal dimensions, requiring concerted effort from researchers, clinicians, policymakers, and ethicists.

3.1 Data Privacy and Security

The efficacy of deep learning models is directly correlated with the quantity and quality of data used for their training. In medical imaging, this necessitates access to vast repositories of patient images, often linked with sensitive clinical data. This requirement raises profound concerns regarding data privacy and security, which are paramount in healthcare and subject to stringent regulatory frameworks globally.

- Regulatory Compliance: Healthcare institutions must navigate complex legal landscapes such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in the United States and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union. These regulations impose strict requirements on how personal health information (PHI) can be collected, stored, processed, and shared. Non-compliance can lead to severe penalties, loss of public trust, and legal ramifications (simbo.ai/blog/ethical-considerations-and-challenges-of-integrating-ai-in-medical-practice-addressing-data-privacy-technology-reliance-and-algorithmic-biases-3739969/).

- Anonymization and De-identification: A primary strategy to protect privacy is to anonymize or de-identify patient data before it is used for model training or research. This involves removing or encrypting direct identifiers (names, dates, medical record numbers) and indirect identifiers that could, in combination, lead to re-identification. Techniques like k-anonymity, l-diversity, and t-closeness aim to ensure that individuals cannot be uniquely identified within a dataset. However, complete de-identification, especially for complex imaging data, is challenging; subtle features in medical images themselves can sometimes be re-identifying, and adversaries can combine de-identified data with external information to re-identify individuals.

- Secure Data Storage and Transfer: Medical imaging data repositories are highly attractive targets for cyberattacks. Robust cybersecurity measures, including strong encryption (at rest and in transit), access controls, intrusion detection systems, and regular security audits, are essential to prevent unauthorized access, data breaches, and data corruption. Cloud-based solutions, while offering scalability, introduce new security considerations regarding vendor trust and shared responsibility models.

- Advanced Privacy-Preserving Techniques: Emerging techniques are being explored to allow machine learning on sensitive data without direct data sharing:

- Federated Learning: This decentralized approach allows deep learning models to be trained on data residing locally at different institutions without the data ever leaving its source. Only model parameters or gradients are shared and aggregated, thus preserving data privacy.

- Homomorphic Encryption: This advanced cryptographic technique enables computations to be performed directly on encrypted data without decrypting it first. While computationally intensive, it offers strong privacy guarantees.

- Differential Privacy: By injecting controlled noise into data or model outputs, differential privacy mathematically guarantees that the presence or absence of any single individual’s data does not significantly alter the outcome, making it difficult to infer individual characteristics.

3.2 Algorithmic Bias

Deep learning models learn from the data they are trained on, and consequently, they inherit and can even amplify biases present in those datasets. In medical imaging, algorithmic bias can lead to disparities in performance across different patient populations, potentially exacerbating existing health inequalities and compromising equitable healthcare delivery.

-

Sources of Bias:

- Dataset Bias: Training datasets may disproportionately represent certain demographic groups (e.g., age, gender, race, socioeconomic status). For example, a model trained predominantly on images from Caucasian males may perform less accurately when applied to African American females. This can stem from unequal access to healthcare, specific recruitment strategies, or historical data collection practices. Cultural biases in image acquisition protocols can also play a role.

- Labeling Bias: Human annotators, often clinicians, may introduce bias into the ground truth labels. For instance, diagnostic criteria might be applied differently across patient groups, or subtle findings might be overlooked in certain populations due to implicit biases.

- Sampling Bias: If the training data is not representative of the real-world patient population where the model will be deployed, it will lead to poor generalization. This can occur if data is collected from a single institution or geographic region.

- Algorithmic Design Bias: The choice of model architecture, loss functions, and optimization strategies can inadvertently favor certain feature representations over others, leading to biased outcomes.

-

Consequences of Bias:

- Misdiagnosis and Delayed Treatment: Biased models may consistently misdiagnose or under-diagnose conditions in underrepresented groups, leading to poorer health outcomes (simbo.ai/blog/challenges-and-ethical-considerations-in-adopting-artificial-intelligence-for-dermatology-image-analysis-managing-diagnostic-errors-and-data-biases-4170776/). For example, a skin cancer detection algorithm trained primarily on fair skin tones may perform poorly on darker skin, where melanoma can present differently.

- Exacerbation of Health Disparities: If AI tools are deployed without addressing bias, they risk widening the gap in healthcare quality between privileged and underserved populations.

- Loss of Trust: If patients and clinicians perceive AI tools as unfair or discriminatory, their adoption will be hindered, undermining the potential benefits.

-

Mitigation Strategies:

- Diverse and Representative Datasets: Actively collecting and curating datasets that accurately reflect the diversity of the target patient population is crucial. This often involves multi-institutional collaborations and international data sharing initiatives.

- Bias Detection and Measurement: Developing metrics and tools to detect and quantify bias (e.g., subgroup performance analysis, fairness metrics like demographic parity, equalized odds, predictive equality) is essential during model development and validation.

- Bias Mitigation Algorithms: Techniques such as re-sampling, re-weighting, adversarial de-biasing, and constrained optimization can be employed during training to reduce algorithmic bias.

- Fairness-Aware Design: Integrating fairness considerations into the entire machine learning pipeline, from data collection to model deployment and monitoring.

- Transparent Reporting: Explicitly stating the demographics of the training data and known limitations of the model’s performance across different subgroups.

3.3 Interpretability and Transparency

The ‘black box’ nature of many complex deep learning models, particularly deep neural networks with millions of parameters, presents a significant challenge in medical contexts. Unlike traditional rule-based expert systems, it can be difficult to ascertain how a deep learning model arrives at a particular decision, which is a critical requirement in medicine where explanations are necessary for clinical decision-making, legal accountability, and building trust.

-

Importance of Interpretability:

- Clinical Trust and Adoption: Clinicians need to understand the rationale behind an AI’s recommendation to trust it and integrate it into their workflow. Blindly accepting AI outputs is risky and undermines professional autonomy.

- Error Detection and Debugging: Without interpretability, diagnosing why a model failed or made an incorrect prediction is extremely difficult. Understanding failure modes is essential for model improvement and patient safety.

- Medical-Legal Accountability: In cases of misdiagnosis or adverse events involving AI, establishing accountability requires understanding the model’s decision-making process (journals.lww.com/medmat/abstract/9900/the_ethical_implications_of_emerging_ai.14.aspx).

- Scientific Discovery: Interpretable AI can potentially reveal novel biomarkers or previously unknown correlations in medical images, advancing scientific understanding.

- Patient Engagement: Explaining AI-driven diagnoses or treatment plans to patients requires a degree of transparency in the AI’s reasoning.

-

Interpretability Techniques (Explainable AI – XAI):

- Post-hoc Interpretability: Methods applied after a model is trained to explain its predictions:

- Feature Importance Methods: Techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) approximate the contribution of individual input features (e.g., pixels or regions in an image) to a specific prediction.

- Saliency Maps/Attention Maps: Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) and similar methods highlight regions in the input image that were most influential for the model’s decision, providing visual explanations.

- Concept-based Explanations: Instead of pixel-level explanations, these methods identify higher-level concepts (e.g., ‘presence of calcification’, ‘texture irregularity’) that the model relies on.

- Intrinsic Interpretability (Interpretable by Design): Developing models that are inherently more understandable, such as:

- Simpler Models: Using linear models or decision trees where appropriate, though often less powerful for complex imaging tasks.

- Attention Mechanisms: Incorporating explicit attention layers within deep neural networks allows the model to ‘focus’ on specific parts of the input, making its process more transparent.

- ProtoPNet (Prototypical Part Network): A type of network that learns to classify images by comparing parts of the input image to learned prototypes, offering case-based explanations.

- Post-hoc Interpretability: Methods applied after a model is trained to explain its predictions:

-

Challenges in XAI for Medicine: While promising, current XAI techniques are often limited. They might provide ‘where’ the model looked, but not necessarily ‘why’ or ‘how’ it combined features. Furthermore, explanations must be clinically relevant and understandable to practitioners, not just technically accurate.

3.4 Data Availability and Annotation

The unparalleled success of deep learning is predicated on the availability of massive, high-quality, and meticulously annotated datasets. This requirement poses a significant hurdle in medical imaging, where data acquisition and labeling are inherently complex and resource-intensive.

- Scarcity of Large, Diverse Datasets: Medical data is typically siloed within individual institutions due to privacy regulations and competitive concerns. Aggregating data from multiple sites to create sufficiently large and diverse datasets for deep learning is a monumental task. Furthermore, certain rare diseases have inherently limited data available.

- Expert Annotation Requirement: Accurate ground truth labels for medical images (e.g., precise tumor boundaries for segmentation, definitive diagnoses for classification) require highly skilled and often subspecialized clinicians (radiologists, pathologists). This process is extremely time-consuming, expensive, and subject to inter-observer variability, which can introduce noise into the training labels.

- Data Imbalance: Many medical conditions are rare, leading to imbalanced datasets where the number of positive cases is significantly smaller than negative cases. This can cause deep learning models to perform poorly on the minority class, potentially missing critical diagnoses.

- Addressing the Challenge:

- Data Augmentation: Techniques like geometric transformations (rotation, scaling, flipping), intensity variations, and adversarial examples can artificially expand existing datasets, reducing overfitting and improving generalization.

- Generative Models: GANs and variational autoencoders can generate synthetic medical images, which can be used to augment training data, particularly for rare conditions, while preserving privacy.

- Transfer Learning and Pre-training: Leveraging models pre-trained on large natural image datasets (e.g., ImageNet) and fine-tuning them on smaller medical datasets can be effective, as initial layers learn general visual features applicable to many domains.

- Weakly Supervised Learning: Developing methods that can learn from less precise or abundant annotations (e.g., image-level labels instead of pixel-level masks) can alleviate annotation burden.

- Active Learning: Strategically selecting the most informative unlabeled samples for expert annotation can optimize the use of limited expert resources.

3.5 Generalizability and Robustness

For deep learning models to be clinically useful, they must reliably perform across different patient populations, imaging protocols, scanner manufacturers, and clinical environments. This quality, known as generalizability, is often a significant challenge.

- Domain Shift: A model trained at one institution with specific scanner parameters and patient demographics may perform poorly when deployed at another institution with different characteristics. This ‘domain shift’ can severely limit real-world applicability.

- Robustness to Perturbations: Medical images often contain artifacts or noise due to acquisition variations. Models must be robust to these minor, often unavoidable, imperfections. Furthermore, concerns exist about adversarial attacks, where imperceptible perturbations to an input image can cause a model to make drastically wrong predictions.

- Mitigation Strategies:

- Multi-site Data Collection: Training on data from diverse institutions helps improve generalizability across different acquisition protocols and patient cohorts.

- Domain Adaptation Techniques: Algorithms designed to adapt a model trained on a source domain to perform well on a target domain without requiring extensive re-labeling of target data.

- Rigorous Validation: Comprehensive external validation on independent, unseen datasets from various clinical sites is critical before clinical deployment.

- Uncertainty Quantification: Models that can quantify their confidence in a prediction are invaluable, allowing clinicians to appropriately weight AI recommendations and intervene when uncertainty is high.

3.6 Regulatory Approval and Integration into Clinical Workflow

Medical devices, including AI-powered diagnostic tools, are subject to stringent regulatory approval processes (e.g., FDA in the US, CE Mark in Europe). Navigating this complex landscape is a major challenge for developers.

- Validation Requirements: Regulators demand rigorous validation studies demonstrating the safety, effectiveness, and clinical utility of AI tools. This often involves large-scale prospective clinical trials, which are time-consuming and expensive.

- Post-Market Surveillance: Approved AI models require continuous monitoring in real-world settings to detect any degradation in performance, new biases, or unexpected behaviors.

- Integration Challenges: Even after approval, integrating AI tools seamlessly into existing clinical workflows (e.g., Picture Archiving and Communication Systems – PACS, Radiology Information Systems – RIS) can be complex. User interfaces must be intuitive, and the tools must not disrupt or overburden clinicians’ existing routines.

- Socio-Technical Integration: Clinicians must be trained on how to use, interpret, and critically evaluate AI outputs. Resistance to change or lack of trust can hinder adoption, even with highly effective tools.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

4. Ethical Considerations

The integration of deep learning into medical imaging raises a series of profound ethical considerations that demand careful attention to ensure responsible and patient-centric deployment. As these technologies become more capable and autonomous, society must grapple with their impact on human values, justice, and the established norms of medical practice.

4.1 Informed Consent

Informed consent is a cornerstone of ethical medical practice, ensuring that patients have autonomous control over decisions related to their health and personal data. The use of patient medical images, and indeed their entire medical records, in developing, training, validating, and deploying deep learning models introduces new layers of complexity to this principle.

-

Scope of Consent: Traditional informed consent forms often cover specific procedures or research studies. However, AI development often uses retrospective, aggregated datasets for purposes that may not have been explicitly envisioned at the time of initial data collection. Patients should be clearly informed about:

- The purpose for which their data (including imaging data) will be used in AI development and deployment.

- The types of AI models being developed and their intended clinical applications.

- The potential benefits (e.g., improved diagnostics for future patients) and potential risks (e.g., data breaches, algorithmic bias leading to misdiagnosis).

- How their data will be anonymized, secured, and stored.

- Whether their data will be shared with external researchers or commercial entities.

- The right to withdraw consent for future use of their data, where feasible.

-

Challenges in Obtaining Consent for AI:

- Granularity: Should consent be broad (for general AI research) or highly specific (for each individual AI project)? Overly broad consent may not be truly ‘informed,’ while overly granular consent could be impractical.

- Retrospective Data: Obtaining fresh consent for historical data already collected is often impossible or unduly burdensome, leading to debates about ‘opt-out’ vs. ‘opt-in’ models for secondary data use.

- Dynamic Consent: Proposed models of dynamic consent allow patients to actively manage their data usage preferences over time, providing more granular control and transparency. However, implementing such systems at scale is challenging.

- Understanding AI: Patients may struggle to understand the technical nuances of deep learning, making it difficult to give truly informed consent without clear, accessible explanations. Educational efforts are crucial (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37827839/).

-

Ethical Obligation: Upholding ethical standards requires transparent communication that empowers patients to make informed decisions about the use of their most sensitive personal information for AI development.

4.2 Accountability

Determining responsibility when deep learning models are involved in clinical decision-making is a complex and evolving ethical and legal challenge. In traditional medical practice, accountability for diagnostic errors or adverse patient outcomes typically rests with the human clinician. However, the introduction of AI complicates this clear chain of responsibility.

-

The ‘Responsibility Gap’: When an AI algorithm contributes to an error, who is accountable? Is it:

- The developer of the algorithm (e.g., the software company)?

- The manufacturer of the medical device incorporating the AI?

- The hospital or healthcare institution that acquired and deployed the AI?

- The clinician who used (or chose not to use) the AI’s recommendation?

- The regulator who approved the device?

-

Challenges in Assigning Accountability:

- Black Box Nature: The lack of interpretability in deep learning models makes it difficult to pinpoint why an error occurred, complicating efforts to assign blame or improve the system. Was it a data error, an algorithmic flaw, or human misuse?

- Human-in-the-Loop vs. Autonomous AI: Most current AI in medical imaging functions as a decision-support tool, with a human clinician retaining final authority. In such cases, the human is usually considered accountable. However, as AI becomes more autonomous, this distinction blurs. What if the human clinician ignores an AI recommendation that turns out to be correct, or blindly follows an AI recommendation that turns out to be wrong?

- Shared Responsibility: A more realistic view is that accountability may be shared across multiple stakeholders, requiring new legal and ethical frameworks to delineate responsibilities clearly (journals.lww.com/medmat/abstract/9900/the_ethical_implications_of_emerging_ai.14.aspx).

- Continuous Learning Models: Some AI models are designed to continuously learn and adapt in real-time. This dynamic nature further complicates accountability, as the model’s behavior might change after deployment.

-

Need for Clear Guidelines: Establishing clear guidelines on accountability, perhaps through regulatory bodies, professional organizations, and hospital policies, is essential to ensure patient safety, maintain public trust, and incentivize responsible AI development and deployment. This includes defining the standard of care for using AI tools and the responsibilities of all parties involved.

4.3 Fairness and Equity

As previously discussed under algorithmic bias, ensuring that deep learning models do not perpetuate or exacerbate existing biases and inequalities in healthcare is a paramount ethical concern. Fairness, in the context of AI, refers to the principle that AI systems should not systematically disadvantage particular groups of people.

-

Dimensions of Fairness: Fairness is a multifaceted concept, and different definitions exist:

- Demographic Parity: Requires that the model’s positive prediction rate is the same across different demographic groups (e.g., equal rates of diagnosing a condition in males and females).

- Equalized Odds: Demands that the true positive rates and false positive rates are equal across groups (e.g., the model should be equally good at correctly identifying sick individuals and correctly identifying healthy individuals, regardless of group membership).

- Predictive Equality: Suggests that the false positive rates should be equal across groups.

- Predictive Parity: Requires that the positive predictive value (precision) is equal across groups.

-

Challenges and Implications: Achieving fairness across all these dimensions simultaneously is often mathematically impossible. Developers must make explicit choices about which fairness metric is most critical for a given clinical application, often in consultation with stakeholders and ethicists. For instance, in cancer screening, a higher false positive rate in a particular group might be acceptable if it ensures fewer missed diagnoses (higher true positive rate) in that group, especially if the consequences of a missed diagnosis are severe.

-

Ensuring Equitable Access: Beyond algorithmic fairness, there is the broader ethical concern of equitable access to AI-enhanced healthcare. If advanced AI diagnostics are expensive or only available in affluent regions, they could further widen the gap in healthcare quality between different socioeconomic groups or geographical areas. Efforts must be made to develop cost-effective solutions and ensure their availability to all patient populations, including those in low-resource settings (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37827839/).

4.4 Professional Role Changes and Human Autonomy

The introduction of highly capable AI systems into medical practice will inevitably lead to shifts in professional roles and raises questions about human autonomy—both for clinicians and patients.

- Impact on Clinicians (e.g., Radiologists): AI is unlikely to replace human radiologists entirely but will profoundly change their role. Radiologists may spend less time on routine tasks and more time on complex cases, interdisciplinary collaboration, and communication with patients. The ethical concern arises if AI deskills clinicians or reduces their diagnostic intuition over time. It is crucial to design AI as an augmentation tool, empowering clinicians rather than diminishing their expertise.

- Patient Autonomy: While AI can improve diagnostic accuracy, patients might feel reduced autonomy if decisions are perceived as machine-driven rather than human-centered. The ‘right to explanation’ concerning AI decisions is crucial for patients to understand their health status and make informed choices about treatment.

4.5 Beneficence and Non-maleficence

The fundamental ethical principles of beneficence (doing good) and non-maleficence (doing no harm) are central to medical ethics and apply equally to the deployment of deep learning in healthcare.

- Maximizing Benefit: AI should be developed and used to genuinely improve patient care, reduce suffering, and enhance health outcomes. This requires rigorous testing to prove clinical utility and ensure that benefits outweigh potential risks.

- Minimizing Harm: All potential harms, including misdiagnosis due to bias, data breaches, over-reliance on AI, or even psychological distress from AI-generated prognoses, must be systematically identified and mitigated. The ethical imperative is to anticipate unintended consequences and design safeguards.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

5. Conclusion

Deep learning represents a paradigm shift with immense promise for revolutionizing medical imaging, offering unprecedented capabilities to enhance diagnostic precision, optimize treatment planning, and ultimately elevate the standard of patient care. Its demonstrated prowess in tasks such as intricate image segmentation, sophisticated reconstruction from raw data, and the synergistic analysis of multimodal imaging assets signifies a pivotal advancement in the field. From automating routine tasks and reducing inter-observer variability to identifying subtle pathological patterns invisible to the human eye and accelerating time-sensitive diagnoses, deep learning holds the potential to make healthcare more efficient, accurate, and accessible.

However, realizing the full transformative potential of deep learning in clinical practice necessitates a meticulous and considered approach that critically addresses its inherent technical challenges and profound ethical implications. The journey from research breakthrough to routine clinical integration is fraught with hurdles. Safeguarding the privacy and security of sensitive patient data, particularly through robust anonymization techniques, federated learning, and stringent cybersecurity protocols, remains a paramount concern. Simultaneously, the persistent threat of algorithmic bias demands proactive strategies to curate diverse and representative datasets, develop fairness-aware algorithms, and rigorously evaluate model performance across all demographic groups to prevent the perpetuation or exacerbation of health disparities.

Furthermore, the ‘black box’ nature of many deep learning models underscores the critical need for greater interpretability and transparency. Clinicians require clear, actionable insights into how AI models arrive at their decisions to build trust, validate recommendations, and ensure accountability. Developing robust Explainable AI (XAI) methods that are clinically relevant is essential for fostering widespread adoption and ethical oversight. Beyond these technical and practical challenges, the ethical landscape demands careful navigation. Comprehensive informed consent processes must empower patients with a clear understanding of how their data is utilized for AI development. Clear frameworks for accountability are essential to delineate responsibility in cases of AI-related errors, ensuring patient safety and maintaining public confidence. Finally, an unwavering commitment to fairness and equity must guide every stage of AI development and deployment, guaranteeing that these powerful tools serve all individuals justly and without discrimination.

The responsible integration of deep learning into medical imaging is not merely a technical endeavor; it is a complex socio-technical and ethical undertaking. It requires sustained multidisciplinary collaboration among artificial intelligence researchers, medical professionals, data scientists, ethicists, legal experts, and policymakers. By proactively addressing issues related to data governance, bias mitigation, interpretability, informed consent, accountability, and fairness, we can ethically harness the immense potential of deep learning to drive meaningful improvements in diagnostic accuracy, therapeutic efficacy, and overall patient well-being, ultimately shaping a future where advanced technology serves as a powerful ally in the pursuit of optimal human health.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

References

- ajesjournal.org. (n.d.). Automated Brain Tumor Segmentation from Multi-modal MRI using Deep Learning: A Survey. Retrieved from https://ajesjournal.org/index.php/ajes/article/view/4254

- en.wikipedia.org. (n.d.). Deep tomographic reconstruction. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deep_tomographic_reconstruction

- journals.lww.com. (n.d.). The Ethical Implications of Emerging AI. Retrieved from https://journals.lww.com/medmat/abstract/9900/the_ethical_implications_of_emerging_ai.14.aspx

- pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. (n.d.). Deep learning for multimodal medical image fusion and classification: A review. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34722958/

- pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. (n.d.). Ethics of artificial intelligence in healthcare: An overview of recommendations and a call for a responsible ecosystem. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37827839/

- simbo.ai. (n.d.). Challenges and Ethical Considerations in Adopting Artificial Intelligence for Dermatology Image Analysis: Managing Diagnostic Errors and Data Biases. Retrieved from https://www.simbo.ai/blog/challenges-and-ethical-considerations-in-adopting-artificial-intelligence-for-dermatology-image-analysis-managing-diagnostic-errors-and-data-biases-4170776/

- simbo.ai. (n.d.). Ethical Considerations and Challenges of Integrating AI in Medical Practice: Addressing Data Privacy, Technology Reliance, and Algorithmic Biases. Retrieved from https://www.simbo.ai/blog/ethical-considerations-and-challenges-of-integrating-ai-in-medical-practice-addressing-data-privacy-technology-reliance-and-algorithmic-biases-3739969/

Be the first to comment