Polypharmacy in Chronic Disease Management: A Critical Appraisal of Efficacy, Safety, and Future Directions

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

Abstract

Polypharmacy, defined as the concurrent use of multiple medications, has become increasingly prevalent in the management of chronic diseases. While often necessary to achieve therapeutic goals in complex conditions, polypharmacy also carries significant risks, including adverse drug events, drug-drug interactions, reduced adherence, and increased healthcare costs. This research report provides a comprehensive overview of polypharmacy in the context of chronic disease management, examining the factors contributing to its rise, the associated challenges, and strategies for optimizing its use. We delve into specific examples across different therapeutic areas, evaluate the evidence regarding combination therapies, explore emerging technologies for medication management, and discuss future directions for research and clinical practice. The report emphasizes the need for individualized treatment approaches, careful medication reconciliation, and ongoing monitoring to maximize the benefits and minimize the harms of polypharmacy.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

1. Introduction

The escalating prevalence of chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and mental health disorders, has led to a corresponding increase in polypharmacy. Defined most commonly as the concurrent use of five or more medications, polypharmacy is now a common feature in the management of these conditions, particularly in older adults who often experience multiple comorbidities. While the judicious use of multiple medications can be life-saving and improve quality of life, inappropriate polypharmacy poses substantial risks to patient safety and economic burden to healthcare systems.

This report aims to provide a critical appraisal of polypharmacy in chronic disease management. It explores the complex interplay of factors that contribute to its rise, the associated risks and benefits, and the strategies that can be employed to optimize medication use and minimize harm. The report also examines the role of emerging technologies and future research directions in addressing the challenges of polypharmacy.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

2. Factors Contributing to the Rise of Polypharmacy

Several interconnected factors have fueled the increasing prevalence of polypharmacy:

-

Increased Prevalence of Chronic Diseases: The aging global population and lifestyle factors (e.g., poor diet, physical inactivity, smoking) have contributed to a significant rise in the incidence of chronic diseases. Patients with these conditions often require multiple medications to manage their symptoms and prevent disease progression.

-

Comorbidity: Patients frequently present with multiple co-existing chronic conditions. Managing each condition often requires a separate set of medications, leading to polypharmacy. For example, a patient with diabetes may also have hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and depression, each requiring specific pharmacological interventions.

-

Specialization in Medicine: The increasing specialization of medical practice can lead to fragmented care. Different specialists may prescribe medications without a complete understanding of the patient’s existing medication regimen, increasing the risk of drug interactions and adverse effects. The so-called “siloed” approach to healthcare presents a significant challenge in managing polypharmacy.

-

Evidence-Based Guidelines: Clinical practice guidelines often recommend the use of multiple medications to achieve specific therapeutic targets. While these guidelines are intended to improve patient outcomes, they can inadvertently contribute to polypharmacy, especially when applied rigidly without considering individual patient needs and preferences.

-

Patient Expectations and Demands: Patients may expect or demand medications to treat their symptoms, even when non-pharmacological interventions might be more appropriate. Direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs can also contribute to this pressure.

-

Lack of Effective Communication: Insufficient communication between healthcare providers, patients, and caregivers can result in medication errors, duplications, and omissions, leading to inappropriate polypharmacy.

-

Prescribing Cascade: The prescribing cascade occurs when an adverse drug reaction is misinterpreted as a new medical condition, leading to the prescription of another medication to treat the adverse effect. This can create a vicious cycle of escalating polypharmacy.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

3. Risks and Challenges Associated with Polypharmacy

While polypharmacy can be necessary and beneficial in certain situations, it is associated with several significant risks and challenges:

-

Adverse Drug Events (ADEs): The risk of ADEs increases exponentially with the number of medications a patient is taking. ADEs can range from mild discomfort to severe and life-threatening complications, such as falls, hospitalizations, and death.

-

Drug-Drug Interactions (DDIs): The more medications a patient takes, the greater the likelihood of DDIs. These interactions can alter the absorption, distribution, metabolism, or excretion of one or more drugs, leading to increased toxicity or reduced efficacy.

-

Reduced Adherence: Patients taking multiple medications often find it difficult to adhere to their medication regimens. This can lead to suboptimal treatment outcomes and increased healthcare costs. Complex dosing schedules, cognitive impairment, and poor health literacy can all contribute to non-adherence.

-

Increased Healthcare Costs: Polypharmacy is associated with increased healthcare costs, including medication costs, hospitalizations, and emergency room visits. The costs associated with managing ADEs and DDIs can be substantial.

-

Cognitive Impairment: Certain medications, such as anticholinergics and benzodiazepines, can impair cognitive function, especially in older adults. Polypharmacy involving these medications can exacerbate cognitive decline and increase the risk of dementia.

-

Falls and Fractures: Polypharmacy is a significant risk factor for falls and fractures, particularly in older adults. Medications that cause dizziness, orthostatic hypotension, or impaired balance can increase the risk of falls.

-

Increased Mortality: Studies have shown that polypharmacy is associated with increased mortality, especially in older adults and patients with multiple comorbidities.

-

Reduced Quality of Life: The burden of managing multiple medications, experiencing ADEs, and dealing with the complexities of polypharmacy can negatively impact patients’ quality of life.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

4. Strategies for Optimizing Polypharmacy

Optimizing polypharmacy requires a multi-faceted approach involving healthcare providers, patients, and caregivers:

-

Medication Reconciliation: Medication reconciliation is the process of creating an accurate and complete list of all medications a patient is taking, including prescription drugs, over-the-counter medications, herbal remedies, and dietary supplements. This list should be reviewed and updated at each healthcare encounter to identify discrepancies, duplications, and potential DDIs. This should ideally involve a pharmacist or physician specially trained in geriatric care or medication management.

-

Comprehensive Medication Review: A comprehensive medication review (CMR) is a systematic evaluation of a patient’s medication regimen to identify and resolve medication-related problems. This review should be conducted by a qualified healthcare professional, such as a pharmacist or physician, and should involve a thorough assessment of the patient’s medical history, medication list, and clinical data. The review should address issues such as inappropriate medications, unnecessary medications, potential DDIs, and medication adherence.

-

Deprescribing: Deprescribing is the process of carefully reducing or stopping medications that are no longer needed or are causing more harm than benefit. Deprescribing should be guided by evidence-based guidelines and should involve close monitoring of the patient for withdrawal symptoms or worsening of underlying conditions. It’s not simply stopping medications, but a carefully considered and monitored process.

-

Individualized Treatment Plans: Treatment plans should be tailored to the individual patient’s needs, preferences, and goals of care. Guidelines should be used as a framework, but not as a rigid prescription, acknowledging inter-patient variability.

-

Non-Pharmacological Interventions: Non-pharmacological interventions, such as lifestyle modifications, physical therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy, should be considered as alternatives or adjuncts to medications whenever possible. Promoting healthy lifestyle choices can reduce the need for medications in many cases.

-

Education and Counseling: Patients and caregivers should receive education and counseling about their medications, including their purpose, dosage, administration, potential side effects, and interactions. They should also be encouraged to ask questions and report any concerns they may have. Improving health literacy is key.

-

Collaboration and Communication: Effective communication and collaboration among healthcare providers, patients, and caregivers are essential for optimizing polypharmacy. A team-based approach to care can help ensure that medication regimens are coordinated and that patients receive the support they need to adhere to their medications.

-

Use of Technology: Technology can play a role in optimizing polypharmacy. Electronic health records (EHRs) can provide access to comprehensive patient information, including medication lists, allergy information, and laboratory results. Clinical decision support systems can alert providers to potential DDIs and inappropriate medications. Telehealth can facilitate remote monitoring of patients and medication adherence.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

5. Case Studies in Chronic Disease Management

This section provides case studies illustrating the challenges and strategies associated with polypharmacy in specific chronic diseases.

5.1 Cardiovascular Disease

Patients with cardiovascular disease often require multiple medications to manage hypertension, hyperlipidemia, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation. Polypharmacy in this population can lead to an increased risk of bleeding, electrolyte imbalances, and drug-induced arrhythmias. Strategies for optimizing polypharmacy in cardiovascular disease include careful medication reconciliation, use of fixed-dose combination products, and deprescribing of unnecessary medications, such as aspirin in patients at low risk of cardiovascular events.

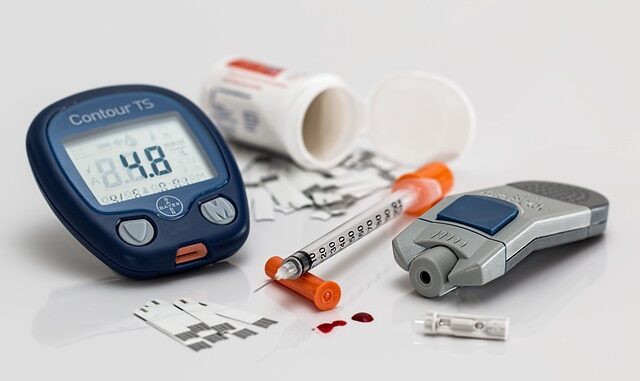

5.2 Diabetes Mellitus

Patients with diabetes often require multiple medications to control blood glucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol. The combination of oral hypoglycemic agents and insulin can increase the risk of hypoglycemia. Strategies for optimizing polypharmacy in diabetes include individualized glycemic targets, use of newer medications with lower risk of hypoglycemia (e.g., SGLT2 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists), and careful monitoring of blood glucose levels.

5.3 Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

Patients with COPD often require multiple medications to manage bronchospasm, inflammation, and infections. The combination of bronchodilators and corticosteroids can increase the risk of pneumonia. Strategies for optimizing polypharmacy in COPD include use of inhaled medications whenever possible, avoidance of unnecessary antibiotics, and deprescribing of anticholinergic medications in patients with cognitive impairment.

5.4 Mental Health Disorders

Patients with mental health disorders often require multiple medications to manage depression, anxiety, psychosis, and insomnia. Polypharmacy in this population can lead to an increased risk of sedation, cognitive impairment, and metabolic side effects. Strategies for optimizing polypharmacy in mental health include careful medication selection, titration of medications to the lowest effective dose, and deprescribing of benzodiazepines and other sedatives.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

6. Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Emerging technologies and future research directions hold promise for improving the management of polypharmacy:

-

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML): AI and ML algorithms can be used to identify patients at high risk of ADEs and DDIs, predict medication adherence, and personalize medication regimens. These technologies can analyze large datasets to identify patterns and relationships that may not be apparent to clinicians.

-

Pharmacogenomics: Pharmacogenomics is the study of how genes affect a person’s response to drugs. Pharmacogenomic testing can help identify patients who are more likely to experience ADEs or who may require different dosages of certain medications. The application of pharmacogenomics is still in its early stages, but it has the potential to revolutionize medication management.

-

Smart Pillboxes and Medication Adherence Technologies: Smart pillboxes and other medication adherence technologies can help patients remember to take their medications and can provide real-time feedback to healthcare providers about adherence. These technologies can improve medication adherence and reduce the risk of ADEs.

-

Nanotechnology: Nanotechnology can be used to develop novel drug delivery systems that improve drug efficacy and reduce side effects. For example, nanoparticles can be used to target drugs to specific tissues or cells, reducing systemic exposure and minimizing off-target effects.

-

Improved Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS): CDSS can be improved by incorporating more sophisticated algorithms, integrating data from multiple sources, and providing more personalized recommendations. CDSS can help clinicians make more informed decisions about medication management and reduce the risk of inappropriate polypharmacy.

-

Research on Deprescribing Strategies: Further research is needed to develop and evaluate deprescribing strategies for different patient populations and medication classes. This research should focus on identifying the best methods for safely and effectively reducing or stopping medications that are no longer needed or are causing more harm than benefit. Deprescribing needs rigorous study to validate optimal strategies.

-

Enhanced Education and Training: Increased education and training for healthcare providers, patients, and caregivers on the risks and benefits of polypharmacy and the strategies for optimizing medication use are crucial. Educational initiatives should focus on improving health literacy and promoting shared decision-making.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

7. Conclusion

Polypharmacy is a complex and growing challenge in chronic disease management. While often necessary to achieve therapeutic goals, it also carries significant risks, including ADEs, DDIs, reduced adherence, and increased healthcare costs. Optimizing polypharmacy requires a multi-faceted approach involving healthcare providers, patients, and caregivers. Strategies such as medication reconciliation, comprehensive medication review, deprescribing, and individualized treatment plans can help minimize the risks and maximize the benefits of polypharmacy. Emerging technologies and future research directions hold promise for further improving the management of polypharmacy and enhancing patient safety and outcomes. A shift towards a more holistic and patient-centered approach to medication management is essential to address the challenges of polypharmacy effectively.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

References

- Guthrie B, Makubate B, Mercer SW, et al. The effects of polypharmacy on health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Medicine. 2015;13:74.

- Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 2014;13(1):57-65.

- American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60(10):E2-E15.

- Farrell B, Shamji SM, Monahan A, et al. The impact of deprescribing interventions on medication use and clinical outcomes: an umbrella review. Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 2018;71(3):182-194.

- Page AT, Potter K, Clifford R, et al. Defining and measuring potentially inappropriate medications in older populations: a review. Drugs & Aging. 2018;35(7):557-575.

- WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC/DDD Index 2023. https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/. Accessed October 26, 2023.

- National Institute on Aging. Medicines and Older Adults. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/medicines-older-adults. Accessed October 26, 2023.

- Rochon PA, Gurwitz JH. Optimising drug prescribing for older people. BMJ. 1995;311(7015):1353-1354.

- Thomas RE. Clinical decision support systems (CDSS): a systematic review. The American Journal of Managed Care. 2020;26(2):e43-e52.

- Kaufman KR, Jaramillo RJ. Polypharmacy management and deprescribing strategies in the geriatric population. P & T. 2023;48(5):172-179.

- Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, et al. High risk prescribing and use of medications among older community-dwelling men: prevalence, predictors, and associations with health outcomes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010;58(7):1352-1361.

- Marcum ZA, et al. Prevalence of anticholinergic medication use among community-dwelling older adults. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2016;315(18):1964-1974.

- Qato DM, Wilder J, Gu Q, et al. Changes in prescription medication use among adults aged 65 years and older in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016;176(4):473-482.

- Shah BM, Hanlon JT. Managing polypharmacy in older adults. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/managing-polypharmacy-in-older-adults. Accessed October 27, 2023.

- Bayer AJ, et al. Adverse drug events in older people. Lancet. 2020;396(10267):2003-2014.

Deprescribing, huh? Sounds like a polite way of saying “oops, maybe we overdid it with the pills.” Wonder if there’s an app for tracking all this, or do I need to hire a personal pharmacist now?

That’s a great point about the need for better tracking! While a personal pharmacist would be amazing, there are actually some promising apps and digital tools emerging to help manage medications and potential interactions. Definitely an area to watch for innovation! Perhaps your local pharmacist can help you.

Editor: MedTechNews.Uk

Thank you to our Sponsor Esdebe

So, if simply reducing the number of medications is “deprescribing,” does that mean we get bonus points for stopping the *right* meds? Or is that just…good medicine?

That’s a fantastic way to frame it! Focusing on stopping the *right* meds highlights the importance of thoughtful, patient-centered deprescribing. It’s not just about quantity, but quality and appropriateness. Highlighting cases where deprescribing has improved health outcomes may improve patient and physician appetite for deprescribing. Thanks for sparking this discussion!

Editor: MedTechNews.Uk

Thank you to our Sponsor Esdebe