Beyond the Bot: Crafting Human-Centred AI for Elder Care

The global population is undeniably aging, and as that demographic shift accelerates, we’re witnessing an unprecedented demand for compassionate, effective, and sustainable elder care solutions. It’s a complex puzzle, isn’t it? Hospitals are often stretched thin, care homes are battling staffing shortages, and families, while wanting the best for their loved ones, can’t always provide round-the-clock support. So, where do we turn? Increasingly, minds are turning towards technology, specifically the integration of social robots into geriatric care.

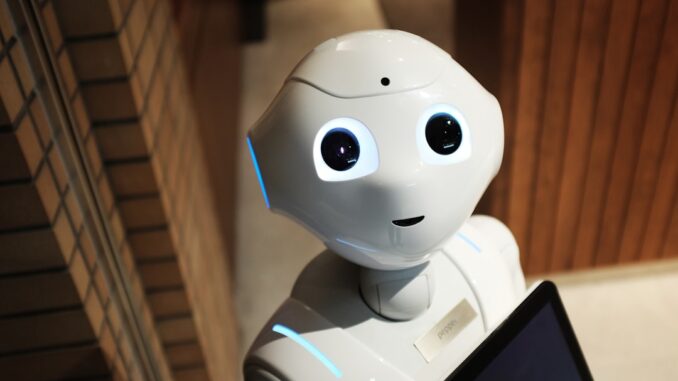

These aren’t just industrial machines; we’re talking about sophisticated AI-driven companions designed to assist with a myriad of daily activities. They can offer companionship, ensuring no one feels truly alone, help monitor vital health metrics, or even provide gentle reminders for medication. The potential here, honestly, it’s immense. These robots could fundamentally transform how we approach aging, fostering greater independence and, critically, enhancing the overall quality of life for our older adults.

But here’s the kicker: the true success of such groundbreaking technologies isn’t just about their technical prowess. It’s not simply about whether they can perform a task flawlessly. No, it hinges entirely on their acceptance and usability among the very people they’re meant to serve – our seniors. And this, my friends, is where the design process becomes paramount. Because if a robot is clunky, confusing, or just plain off-putting, it won’t matter how smart it is under the hood, will it? It just won’t get used.

The Imperative of Human-Centred Design in Eldercare Robotics

Traditional design methodologies, you know, the ones where engineers and programmers hash out a product in a lab, then push it out to the market, they simply fall short when it comes to the nuances of elderly care. This demographic isn’t a monolith; it’s incredibly diverse, encompassing individuals with varying levels of physical dexterity, cognitive function, sensory abilities, and, let’s not forget, wildly different relationships with technology. What works for a tech-savvy 70-year-old who’s been online for decades certainly won’t for an 85-year-old who’s never touched a smartphone.

This is precisely why participatory design has emerged as a shining beacon. It’s a truly collaborative approach that deliberately brings end-users – the actual people who will interact with the technology day in and day out – into the design and development process from the very outset. It’s about co-creation, not just consultation. Think of it as inviting everyone to the table, giving them a voice, and genuinely listening to what they have to say.

For elder care robots, this means assembling a diverse, multidisciplinary team. It’s not just the engineers and product designers, though they’re certainly crucial. You’ve got to involve:

- Older Adults Themselves: This is non-negotiable. And not just one type! Consider those with early-stage cognitive decline, those with mobility issues, and those who are still incredibly active. Their direct experiences are invaluable.

- Family Caregivers: They see the daily routines, the specific struggles, the emotional needs that might not be immediately apparent. They can offer insights into the practicalities of integrating a robot into a home environment.

- Professional Caregivers: Nurses, geriatric specialists, physical therapists – they understand clinical workflows, safety protocols, and the broader healthcare ecosystem. What tools do they really need to make their jobs easier and improve patient outcomes?

- Psychologists and Sociologists: These experts can help us navigate the complex ethical and social implications. How might a robot affect a senior’s sense of autonomy? What are the potential risks of emotional over-reliance or social isolation? They ensure we’re not just building a product, but a responsible solution.

- Ethicists: Seriously, this isn’t just an afterthought. Embedding ethical considerations from the conceptual stage helps preempt thorny issues down the line.

By weaving together these diverse perspectives, designers can create solutions that aren’t just functional, but also intuitively user-friendly, culturally sensitive, and, most importantly, genuinely beneficial. It’s an iterative dance, a process of designing, testing, gathering feedback, and refining, refining, refining.

Consider the development of the SPRING robots, for instance, an excellent case in point for participatory design in action. These weren’t just theoretical constructs; they were designed specifically to offer comfort and reduce anxiety among hospital patients, a particularly vulnerable population. Academic researchers across Europe and the Middle East brought these prototypes into real-world settings, collaborating with elderly patients in their trials. The robots successfully completed their testing phase, engaging with seniors by greeting them, providing directions within the hospital, and answering common questions. What makes this significant? It wasn’t just about the robot’s ability to process language or navigate a hallway; it was the iterative feedback loop with the elderly patients themselves that refined the robot’s tone, its pace of speech, its perceived helpfulness. This direct input ensured the final product genuinely met the users’ needs, demonstrating just how potent participatory design can be in creating truly effective robots for older adults.

Tangible Advantages: Why Involving Seniors Makes All the Difference

Inviting older adults to the design table isn’t just a nice-to-have; it’s a strategic imperative that yields concrete, measurable benefits. You’ll see improvements across the board.

Enhanced Usability: Beyond the Buttons

When older adults contribute directly to the design, the robots that emerge are simply more intuitive and accessible. We’re talking about designs that reduce the learning curve dramatically, encouraging daily use rather than gathering dust in a corner. Think about it: a younger designer might assume a sleek touch screen is ideal, but an elder with arthritis might advocate for large, tactile buttons, or perhaps voice commands. They might point out that brightly colored, high-contrast displays are easier to read, or that a slower response time for confirmation messages actually reduces anxiety.

For example, I remember a conversation I had with my grandmother. She struggled endlessly with her ‘smart’ TV remote, which had dozens of tiny, undifferentiated buttons. ‘Why can’t it just do what I tell it to?’ she’d lament, frustrated. If she’d been part of its design, perhaps the remote would have had five large, clearly labeled buttons and a robust voice control system. That’s the kind of practical insight you gain. Participatory design means focusing on simplified interfaces, clear visual cues, and features that genuinely cater to potential sensory or motor limitations. It means less cognitive load, more spontaneous interaction, and a much smoother daily experience for everyone.

Increased Trust and Acceptance: Building Bridges, Not Walls

Perhaps the most profound benefit is the cultivation of trust. When users feel their needs and concerns are not only heard but actively incorporated into the final product, they develop a sense of ownership and confidence in the technology. It’s human nature, isn’t it? If you’re involved in creating something, you’re far more likely to embrace it. Initial skepticism, which is entirely natural when introducing something as novel as a social robot, can dissipate quickly. An elder who participated in trials might tell their friends, ‘They actually listened to me! They changed the robot’s voice because I found it too loud.’ That’s powerful.

This trust isn’t just about functionality; it’s deeply psychological. It transforms the robot from an intimidating piece of foreign machinery into a helpful, reliable companion. I’ve heard stories of seniors who were initially wary, even resistant, but after a few weeks of interacting with a robot they had a hand in shaping, they became its staunchest advocates, showing it off to visitors as ‘my little helper.’ This emotional connection, facilitated by feeling valued in the design process, is something you simply can’t force.

Improved Functionality and Relevance: Solving Real Problems

Direct feedback from older adults and their caregivers allows designers to identify and address potential issues early on. This isn’t just about ironing out bugs; it’s about ensuring the robot actually solves the right problems in the right way. You might design a robot to remind someone to take their pills, but an older adult might tell you, ‘It’s not just the reminder; I need to know which pills, at what time, and can it tell my daughter if I miss a dose?’ These are granular, practical details that only come from lived experience.

For instance, the study involving the humanoid robot NAO at a care center in Poland highlighted this beautifully. Initial attitudes among the elderly residents were mixed, as you might expect. Some were curious, others apprehensive. But through prolonged, participatory interaction with NAO – which involved the residents teaching the robot new gestures, sharing stories, and playing games – their attitudes shifted dramatically. The study wasn’t just about observing, but actively engaging them. It underscored that when seniors are involved in defining the interactions, when the robot adapts to their preferences (perhaps it learned to play a specific polka for one resident, or patiently explained a weather forecast), the technology becomes truly meaningful. It’s this deep engagement, a result of participatory design, that leads to robots genuinely meeting needs, rather than just theoretically addressing them. Functionality, after all, is only as good as its relevance to the user’s daily life.

Navigating the Labyrinth: Challenges and Ethical Quandaries

While the promise of social robots in elder care is tantalizing, we’d be naive to ignore the significant hurdles that remain. It’s a journey fraught with complexity, and ignoring these challenges would be a disservice to the very people we aim to help.

Technological Barriers – A Deeper Look

Beyond just complex interfaces, several technological nuances can impede adoption. Older adults might struggle with software updates, requiring assistance or leading to outdated, vulnerable systems. Battery life can be a constant concern; a robot that dies in the middle of a crucial task is worse than no robot at all. Network stability, especially in rural areas or older homes, can be unreliable, rendering cloud-dependent functions useless. Then there are the physical limitations: a robot might be too heavy for some to move, or its charging dock might be difficult to access due to dexterity issues.

We also have to consider the digital divide. Many older adults simply haven’t grown up with technology in the same way younger generations have. They might lack the foundational digital literacy that we often take for granted, making even ‘user-friendly’ designs a steep hill to climb. This isn’t just about interface; it’s about familiarity with the concept of interacting with a machine for personal assistance.

Ethical Concerns – The Elephant in the Room

This is perhaps the most critical and emotionally charged aspect. Integrating robots into such an intimate domain as personal care opens up a Pandora’s Box of ethical dilemmas that demand careful, continuous consideration. We simply can’t gloss over them.

- Privacy and Data Security: These robots are monitoring devices. They collect data on routines, conversations, even health metrics. Who owns this data? How is it secured? Could it be used for commercial purposes without consent? The thought of a robot inadvertently leaking sensitive personal information is a chilling one, isn’t it?

- Autonomy vs. Paternalism: When does a robot’s helpful assistance cross the line into control? If a robot reminds someone to eat, that’s helpful. If it prevents them from accessing certain foods based on a pre-programmed diet, does that infringe on their autonomy? The balance between providing support and eroding self-determination is incredibly delicate.

- Social Isolation and Dehumanization: This is a big one. Are we replacing invaluable human contact – the warmth of a caregiver’s touch, the nuance of family conversation – with a machine? While robots can offer companionship, they can’t fully replicate genuine human connection. There’s a real risk of ‘robot sitters’ becoming the norm, leaving older adults feeling even more alone, despite the mechanical presence. We must guard against the insidious erosion of meaningful human relationships.

- Emotional Manipulation: Some robots are designed to be ‘cute’ or to evoke empathy. Where’s the line between endearing and deceptive? If a robot simulates emotions, does that risk infantilizing older adults, treating them as if they can’t distinguish between genuine feeling and programmed responses? It’s a subtle but important distinction.

- Accountability: If a robot makes an error – perhaps it dispenses the wrong medication or fails to alert emergency services in time – who is held responsible? The manufacturer? The programmer? The caregiver? Clear lines of accountability are crucial, but often fuzzy in this emerging field.

Indeed, a systematic qualitative review of the ethical aspects of using social robots in elderly care, like the one highlighted on arxiv.org, underscores precisely this need for a contextual and detailed evaluation of implementation scenarios. It’s not enough to say ‘robots are good’ or ‘robots are bad.’ We must understand the specific ethical discourse relevant to each situation, engaging in careful deliberation, not broad generalizations. This kind of research is vital for creating robust, ethically sound frameworks.

Cultural and Socioeconomic Sensitivity

The perception and acceptance of robots aren’t universal. Cultural norms around aging, the role of family in care, and even the very concept of artificial intelligence vary wildly across the globe. In some cultures, elder care is almost exclusively the domain of the family, and introducing a non-human entity might be seen as an abandonment of responsibility. In others, external help, even technological, might be welcomed. Religious beliefs, too, can play a significant role in how comfortable individuals are with humanoid or anthropomorphic machines.

Furthermore, we must address the socioeconomic disparities. Will these advanced robots become a luxury item, only accessible to the affluent, thereby exacerbating existing inequalities in care? Ensuring affordability and equitable access is a challenge that demands our attention from the get-go. If we’re not careful, we could create a two-tiered system of care, deepening divides rather than bridging them. And let’s not forget the ‘uncanny valley’ effect – that unsettling feeling some people get when robots look almost, but not quite, human. Cultural conditioning often dictates how strongly this effect manifests.

The Horizon: Future Directions and a Collaborative Path Forward

Despite the complexities, the future of social robots in elderly care looks incredibly promising, especially when we consistently apply and refine those participatory design principles we’ve discussed. It’s not a static field; it’s dynamic, evolving almost daily.

Beyond Basic Assistance – Emotional Intelligence and Personalization

Today’s robots can often recognize basic facial expressions or voice tones. Tomorrow’s robots, powered by more advanced AI, will likely interpret subtle shifts in mood, detect early signs of distress, confusion, or even depression, and respond with truly appropriate comfort or alerts. Imagine a robot that notices a senior hasn’t been as active as usual, initiates a gentle conversation, and perhaps suggests a favorite piece of music, or even subtly alerts a family member. These capabilities will move beyond simple task execution to genuinely supporting mental well-being and emotional health. They’ll learn individual preferences over time, personalizing interactions to an unprecedented degree, becoming more akin to a trusted, intelligent confidant rather than just a smart appliance.

Seamless Integration with Existing Ecosystems

Future robots won’t exist in a vacuum. We’ll see them increasingly integrated into broader smart home ecosystems, connecting with telehealth platforms, remote monitoring devices, and even family communication apps. This creates a truly seamless ‘care network’ where information flows freely (and securely), ensuring holistic support. Think of a robot that not only reminds about medication but also verifies consumption, sends data to a doctor, and updates a family portal – all as part of a single, integrated system.

The Role of Regulation and Policy

As the technology matures, so too must the regulatory landscape. Governments and international bodies will need to develop comprehensive standards for safety, data privacy, and ethical deployment. This isn’t just about protecting users; it’s about building public trust and fostering an environment where innovation can thrive responsibly. We’ll likely see incentives for research and adoption, but these must be balanced with robust oversight.

Continual Iteration: The Journey, Not the Destination

Crucially, the design process for these robots isn’t a one-off event. It’s an ongoing journey of feedback, refinement, and adaptation. As technology evolves and as the needs of older adults shift, so too must the robots. This means long-term engagement with users, continuous data analysis, and a commitment to iterative improvement. It’s an endless loop of learning and adapting, really.

In conclusion, integrating social robots into elderly care, particularly when guided by a deep-seated commitment to participatory design, holds truly significant promise. By actively involving older adults – giving them a seat at the table, a voice in the dialogue, and agency in the process – we can develop robots that are not only user-friendly and trustworthy but also genuinely effective in enhancing the quality of life for our seniors. It’s about dignity, efficacy, and acknowledging that even with machines, the human element remains utterly central.

As technology barrels forward, embracing this collaborative, human-centred approach won’t just be helpful; it will be absolutely crucial in addressing the monumental challenges and exciting opportunities presented by social robots in geriatric care. We’re not just building robots; we’re helping to build a better future for our elders, aren’t we? A future where technology serves humanity, with empathy and intelligence. That’s a goal worth striving for, wouldn’t you agree?

The discussion of cultural sensitivity is vital. Has anyone explored tailoring robot appearance or interaction style to align with specific cultural norms and preferences to encourage greater acceptance? Perhaps different models for different regions?

That’s a fantastic point! Exploring tailored robot designs for different cultural norms is key. Imagine robots that use culturally relevant greetings or adapt their storytelling to local traditions. This would definitely boost acceptance and make them more relatable in diverse communities. It’s a exciting field!

Editor: MedTechNews.Uk

Thank you to our Sponsor Esdebe

The article highlights the importance of involving ethicists in the design process. Beyond the principles, what practical frameworks or tools can ethicists use to evaluate and guide the ethical development and deployment of these robots in real-world elder care settings?

That’s a crucial question! Thinking beyond principles, practical frameworks like value-sensitive design and ethical impact assessments can be adapted for elder care robotics. These tools help ethicists proactively identify and mitigate potential ethical risks throughout the robot’s lifecycle, from design to deployment. Extending the conversation, has anyone explored using AI to help ethicists with these complex assessments?

Editor: MedTechNews.Uk

Thank you to our Sponsor Esdebe