Abstract

Biomaterial engineering stands as a cornerstone of modern medicine, continuously pushing the boundaries of therapeutic intervention and regenerative science. This comprehensive report meticulously explores the intricate scientific principles underpinning the design and application of biomaterials, with particular emphasis on bioactive glass-based scaffolds such as the innovative TrabeculeX Bioactive Matrix. This scaffold exemplifies advanced biomaterial design, leveraging a unique surface topography and inherent bioactivity to orchestrate robust osteogenesis and facilitate seamless integration within the skeletal system. We delve into the historical trajectory of biomaterials, tracing their evolution from rudimentary ancient applications to the sophisticated ‘third-generation’ materials engineered for active biological response. A detailed classification based on chemical composition and structural characteristics—encompassing metals, ceramics, polymers, and composites—is presented, highlighting their distinct properties and diverse medical utility. Critical concepts of biocompatibility and biodegradation are elucidated, exploring the complex host-material interactions, the mechanisms governing material breakdown, and the paramount importance of controlled degradation kinetics for successful tissue regeneration. Furthermore, the report dedicates significant attention to the pivotal role of surface modification and micro/nanoscale topography in dictating cellular fate and tissue response, using the TrabeculeX matrix as a prime illustration of intelligent surface design. A broad spectrum of medical applications, from orthopedics and cardiovascular devices to sophisticated drug delivery systems and tissue engineering constructs, underscores the transformative impact of biomaterials. Finally, we address persistent challenges within the field, including infection, immune modulation, and mechanical mismatch, while forecasting future directions encompassing smart biomaterials, advanced manufacturing, and the integration of artificial intelligence, all poised to redefine the landscape of regenerative medicine and implantology.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

1. Introduction

The advent and continuous refinement of biomaterials have ushered in an era of unprecedented progress in medical science, profoundly altering the therapeutic landscape for a myriad of debilitating conditions. From restoring function in compromised joints to regenerating damaged tissues and delivering precise pharmaceutical interventions, biomaterials are indispensable tools in the modern clinician’s arsenal. Within orthopedics, a field constantly seeking superior solutions for skeletal repair and reconstruction, the development of scaffolds that not only provide structural support but actively stimulate physiological healing processes represents a paradigm shift. The TrabeculeX Bioactive Matrix, a contemporary example of a bioactive glass-based scaffold, embodies this advanced philosophy. It stands as a testament to decades of rigorous research and interdisciplinary collaboration, offering a material solution specifically engineered to not merely integrate passively but to profoundly engage with the biological milieu, actively promoting osteogenesis and facilitating the natural process of bone regeneration [1, 3].

To fully appreciate the ingenuity behind innovations like the TrabeculeX Bioactive Matrix, a comprehensive understanding of the overarching principles governing biomaterial science is essential. This includes an exploration of the field’s rich historical evolution, tracing the conceptual and technological advancements that have shaped its current state. Furthermore, a meticulous examination of biomaterial classifications, distinguishing between metals, ceramics, polymers, and composites based on their fundamental properties and structural attributes, is crucial. Such an understanding provides a framework for comprehending why specific materials are chosen for particular applications. Central to the success of any implantable device are the concepts of biocompatibility, the material’s ability to exist harmoniously within a biological system, and biodegradation, the controlled breakdown and eventual absorption of the material by the body. Equally vital is the nuanced interplay between material surface properties—both chemical composition and intricate topography—and cellular responses, as these dictate the initial and long-term biological outcomes. This report will therefore systematically dissect these foundational elements, offering a detailed perspective on how cutting-edge biomaterials are designed, characterized, and deployed to meet the complex demands of clinical medicine, ultimately aiming to improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

2. Historical Overview of Biomaterials

The narrative of biomaterials is as old as human civilization itself, deeply intertwined with our species’ continuous quest to mend and enhance the body. Early instances, while lacking scientific rigor, demonstrated an intuitive understanding of materials that could be integrated with biological systems. Ancient Egyptians, for example, utilized gold for dental restorations and sutures, while various cultures employed ivory, wood, and even seashells for rudimentary prosthetics or structural repairs [8]. These early materials were selected primarily for their mechanical properties, perceived inertness, and availability, with little to no understanding of host-material interactions at a cellular or molecular level.

The modern era of biomaterials, characterized by a systematic, scientific approach, began to emerge in the mid-20th century. The post-World War II period saw significant advancements in metallurgy and polymer chemistry, spurred by military and aerospace research. These innovations soon found their way into medical applications. Early medical metals included stainless steel (specifically 316L stainless steel), which gained prominence in orthopedic implants due to its strength and corrosion resistance, though it was far from ideal [9]. Cobalt-chromium alloys also became widely adopted for their superior wear resistance in articulating joints. Concurrently, the rise of polymer science led to materials like polyethylene (PE) and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), which became foundational for joint replacement components and bone cements, respectively.

However, these ‘first-generation’ biomaterials were largely considered ‘bioinert’—designed to elicit minimal host response, essentially encapsulating the foreign body rather than actively integrating with it [1]. While offering mechanical stability, their inability to bond directly with surrounding tissue often led to issues such as aseptic loosening of implants, requiring revision surgeries. This limitation spurred a new wave of research focused on materials that could actively interact with the biological environment.

A pivotal moment arrived in 1969 with the groundbreaking work of Professor Larry L. Hench at the University of Florida. His serendipitous discovery of the first bioactive glass, Bioglass 45S5, marked the birth of a new paradigm in biomaterials [1]. Hench’s research revealed that specific compositions of silicate glasses could not only survive within the physiological environment but could form a direct, strong chemical bond with bone tissue. This phenomenon, termed ‘bioactivity,’ involved a cascade of surface reactions leading to the formation of a carbonated hydroxyapatite (HCA) layer, chemically analogous to the mineral phase of natural bone. This HCA layer then served as a substrate for osteoblast attachment, proliferation, and differentiation, promoting new bone growth directly onto the implant surface [10, 4]. The development of Bioglass 45S5 fundamentally shifted the focus from bioinertness to active biointegration, laying the groundwork for ‘second-generation’ biomaterials.

Following Hench’s discovery, the field of bioceramics flourished, with further development of bioactive glasses (e.g., S53P4), glass-ceramics (e.g., A/W glass-ceramic), and resorbable ceramics like hydroxyapatite (HA) and tricalcium phosphate (TCP) [5]. The subsequent decades have witnessed an explosion of innovative biomaterials, including sophisticated polymer formulations with tailored degradation rates, novel composite materials combining the best attributes of different classes, and a greater understanding of how surface properties dictate biological response. The ongoing pursuit of materials that actively regenerate tissue, respond to biological cues, and seamlessly integrate into the host system defines ‘third-generation’ biomaterials, often termed ‘bioregenerative materials’ [1]. The TrabeculeX Bioactive Matrix is a prime example of this third generation, building upon the legacy of bioactive glass while incorporating advanced surface design principles to optimize bone regeneration.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

3. Classification of Biomaterials

Biomaterials are broadly classified into several categories based on their fundamental chemical composition and structural characteristics, each possessing unique properties that dictate their suitability for specific medical applications. This classification helps in understanding their mechanical behavior, biocompatibility, and degradation profiles within the complex physiological environment.

3.1. Metals

Metals are a class of biomaterials renowned for their exceptional mechanical strength, stiffness, toughness, and ductility, making them indispensable for load-bearing applications in orthopedics and dentistry. However, their use requires careful consideration of issues such as corrosion, wear, and potential stress shielding due to their typically high elastic modulus compared to bone.

- Stainless Steel: Primarily 316L stainless steel, this alloy of iron, chromium, nickel, and molybdenum offers good mechanical strength and corrosion resistance, particularly when passivated. It is commonly used for temporary implants like bone plates, screws, and fracture fixation devices. However, its long-term corrosion can lead to ion release and potential allergic reactions in some patients, and its higher stiffness compared to bone can cause stress shielding [9].

- Cobalt-Chromium Alloys: These alloys (e.g., CoCrMo) possess superior wear resistance and fatigue strength compared to stainless steel, making them ideal for articulating surfaces in total joint replacements (hip and knee prostheses). While generally corrosion-resistant, concerns about metal ion release and associated inflammatory responses persist [11].

- Titanium and its Alloys: Titanium (Ti) and its alloys, particularly Ti-6Al-4V, are considered the ‘gold standard’ in many orthopedic and dental applications. They offer an excellent balance of high strength-to-weight ratio, exceptional corrosion resistance (due to a stable, passive oxide layer), and crucially, superior biocompatibility compared to stainless steel or cobalt-chromium alloys. Their elastic modulus, while still higher than bone, is closer than other metals, which helps mitigate stress shielding. Titanium surfaces can also be treated to promote osseointegration, the direct structural and functional connection between living bone and the surface of a load-bearing artificial implant [9]. Newer β-titanium alloys are being developed with even lower moduli to further reduce stress shielding.

3.2. Ceramics

Ceramics in biomaterials are inorganic, non-metallic solids characterized by their inertness, biocompatibility, and often, their ability to promote bone growth (osteoconductivity and osteoinductivity). They are typically hard, brittle, and have high compressive strength but low tensile strength.

- Alumina (Al2O3) and Zirconia (ZrO2): These are highly inert, dense ceramics used primarily for their excellent wear resistance and compressive strength. Alumina has been used for articulating surfaces in hip prostheses and dental crowns. Zirconia offers even higher fracture toughness and is increasingly used in dentistry and orthopedics, often in combination with alumina to form ZTA (zirconia-toughened alumina) composites [12]. Their bioinertness means they do not bond directly to bone but provide mechanical stability.

- Hydroxyapatite (HA): Chemically similar to the mineral component of natural bone (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2), synthetic hydroxyapatite is highly osteoconductive, meaning it provides a scaffold for bone ingrowth. It can be used as coatings on metallic implants to enhance osseointegration or as a standalone porous ceramic for bone void fillers. HA exhibits low mechanical strength and brittleness, limiting its use in load-bearing applications [13].

- Bioactive Glasses: As exemplified by Bioglass 45S5 and the material likely underlying the TrabeculeX Bioactive Matrix, these silicate-based glasses are unique in their ability to form a chemical bond with bone and soft tissues. Their bioactivity stems from a controlled series of surface reactions upon exposure to physiological fluids, leading to the formation of a carbonated hydroxyapatite layer that acts as a template for new bone formation [10, 4]. They are osteoconductive and can even exhibit osteoinductive properties, stimulating bone progenitor cells. Their brittleness often limits their use to non-load-bearing applications or as coatings on stronger substrates. The TrabeculeX matrix likely leverages the porous scaffold design of such materials to maximize surface area for bioactivity and tissue ingrowth, while carefully balancing mechanical integrity with tailored degradation kinetics.

- Calcium Phosphates: Beyond HA, other calcium phosphates like tricalcium phosphate (TCP) – specifically alpha-TCP and beta-TCP – are widely used. They are resorbable ceramics, meaning they gradually dissolve and are replaced by new bone. The resorption rate can be tuned by varying the specific calcium phosphate phase and crystallinity, making them excellent bone graft substitutes and delivery vehicles for growth factors [14].

3.3. Polymers

Polymers offer unparalleled versatility in terms of their mechanical properties, processability, and degradation characteristics. They can be engineered to be bioinert, biodegradable, or bioactive, and are derived from either synthetic or natural sources.

-

Synthetic Polymers:

- Polyethylene (PE): Ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) is extensively used for articular surfaces in total joint replacements due to its low friction coefficient and wear resistance. However, wear particle generation remains a long-term challenge [11].

- Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA): Commonly known as bone cement, PMMA is used to fix orthopedic implants to bone, particularly in elderly patients. It polymerizes in situ and provides immediate mechanical stability, although the exothermic reaction during polymerization can be a concern [15].

- Polylactic Acid (PLA) / Polyglycolic Acid (PGA) / Polycaprolactone (PCL): These are prominent examples of biodegradable polyesters. They degrade in vivo via hydrolysis into biocompatible monomers (lactic acid, glycolic acid, caproic acid) that are safely metabolized and excreted. Their degradation rates, mechanical properties, and processing characteristics can be tailored by varying their molecular weight, crystallinity, and copolymerization. They are widely used in resorbable sutures, tissue engineering scaffolds, and drug delivery systems [16].

- Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) / Expanded PTFE (ePTFE): Known for its exceptional chemical inertness and low friction, ePTFE is a common material for vascular grafts due to its smooth surface that resists thrombosis, and its microporous structure allowing tissue ingrowth [17].

- Silicones: Highly flexible and biocompatible, silicones are used in a variety of applications, including breast implants, catheters, and hydrocephalus shunts.

-

Natural Polymers: These polymers are derived from biological sources and often possess inherent biocompatibility and bioactivity due to their similarity to native extracellular matrix (ECM) components.

- Collagen: The most abundant protein in mammals, collagen is a primary component of connective tissues. It is highly biocompatible and can be processed into sponges, gels, and fibers for wound dressings, tissue engineering scaffolds, and drug delivery [18].

- Hyaluronic Acid (HA): A glycosaminoglycan found abundantly in the ECM, HA is known for its viscoelastic properties and role in cell proliferation and migration. It is used in ophthalmic surgery, dermal fillers, and as a component in tissue engineering scaffolds [19].

- Chitin/Chitosan: Derived from crustacean shells, chitosan is a biodegradable and antimicrobial polysaccharide with applications in wound healing, drug delivery, and tissue engineering [20].

- Alginate: A polysaccharide from brown algae, alginate forms hydrogels in the presence of divalent cations, making it suitable for cell encapsulation, drug delivery, and wound dressings [21].

- Silk Fibroin: Known for its excellent mechanical properties, biocompatibility, and tunable degradation, silk fibroin is gaining traction for high-strength tissue engineering scaffolds, particularly for ligaments and tendons [22].

3.4. Composites

Composite biomaterials are engineered by combining two or more distinct materials with different properties, aiming to create a synergistic material that outperforms its individual components. The goal is often to leverage the strength of one material with the biocompatibility or bioactivity of another, or to mimic the hierarchical structure of natural tissues like bone.

- Ceramic-Polymer Composites: These are frequently designed to combine the osteoconductivity of ceramics (e.g., HA, bioactive glass) with the flexibility and processability of polymers (e.g., PLA, PMMA). Examples include bone cements reinforced with HA particles to enhance osteointegration, or resorbable polymer scaffolds incorporating bioactive glass to improve mechanical properties and bioactivity for bone regeneration [23]. The TrabeculeX Bioactive Matrix, while primarily glass-based, could potentially incorporate polymer elements to enhance specific properties or degradation characteristics.

- Metal-Polymer Composites: An example is porous metallic implants infiltrated with polymers to improve fatigue life or create drug-eluting surfaces.

- Natural-Synthetic Polymer Blends: Combining natural polymers (e.g., collagen) with synthetic ones (e.g., PLA) can yield scaffolds that offer both inherent bioactivity and tunable mechanical properties and degradation rates, useful in complex tissue engineering applications [24].

The choice of a biomaterial is a complex decision, driven by the specific clinical application, the required mechanical properties, the desired biological response (inert, bioactive, resorbable), and considerations of processability and cost. The continuous innovation in each of these classes, often leading to the creation of novel composite materials, reflects the dynamic nature of biomaterial engineering.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

4. Biocompatibility and Biodegradation

Two fundamental pillars govern the success of any implantable biomaterial: biocompatibility and controlled biodegradation. These interconnected concepts dictate the material’s interaction with the host tissue, its functionality over time, and ultimately, the patient’s long-term health and well-being. A thorough understanding of these principles is paramount for the design of safe and effective medical devices.

4.1. Biocompatibility

Biocompatibility, as defined by Williams [25], refers to ‘the ability of a material to perform with an appropriate host response in a specific application.’ This definition is critical because it acknowledges that biocompatibility is not an intrinsic property of a material but rather a context-dependent attribute. A material considered biocompatible for a short-term dental filling may not be suitable for a long-term load-bearing orthopedic implant. The ‘appropriate host response’ implies a delicate balance, aiming to avoid adverse reactions while ideally promoting a beneficial, regenerative outcome.

The host response to an implanted biomaterial is a complex cascade of events, often initiated immediately upon implantation. This response involves various cell types, proteins, and signaling molecules, and can be broadly categorized as:

- Initial Biological Events: Upon contact with blood or tissue fluids, the material surface rapidly adsorbs proteins (e.g., albumin, fibrinogen, fibronectin). The composition and conformation of this adsorbed protein layer significantly influence subsequent cellular events, such as platelet adhesion and activation, and immune cell recruitment.

- Inflammatory Response: The body perceives the implant as a foreign object, triggering an acute inflammatory response characterized by the recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages. Macrophages play a crucial role, attempting to phagocytose the foreign material. If the material cannot be degraded, chronic inflammation may ensue, leading to the formation of a foreign body giant cell (FBGC) layer around the implant.

- Wound Healing and Fibrous Encapsulation: Following inflammation, the wound healing process begins, involving fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition. In many cases, particularly with bioinert materials, this culminates in the formation of a dense fibrous capsule around the implant, effectively isolating it from the host tissue. While this can provide stability for some devices, it can also hinder nutrient exchange and prevent desired tissue integration.

- Regenerative Response: For ‘third-generation’ biomaterials like the TrabeculeX Bioactive Matrix, the goal is to bypass or modulate the typical foreign body response and instead promote a regenerative outcome. This involves stimulating specific cell types (e.g., osteoblasts for bone, fibroblasts for skin) to proliferate, differentiate, and deposit new, functional tissue directly onto or into the implant. This requires the material to be osteoconductive, osteoinductive, or otherwise tissue-integrative [1].

Factors influencing biocompatibility are multifaceted:

- Material Chemistry: The elemental composition, bond types, and surface charge significantly impact protein adsorption and cell interactions. For instance, the release of toxic degradation products or leachable components can compromise biocompatibility.

- Surface Properties: As detailed in Section 5, surface topography (roughness, porosity, micro/nano features) and surface chemistry (hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity, presence of functional groups, adsorbed proteins) are paramount in dictating cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation [6].

- Physical Properties: Mechanical properties (stiffness, elasticity) can influence cell behavior (mechanotransduction) and lead to issues like stress shielding if poorly matched with native tissue.

- Implant Geometry and Size: The overall shape, size, and presence of sharp edges can influence local tissue stress and immune response.

- Sterilization Method: The chosen sterilization technique (e.g., autoclaving, ethylene oxide, gamma irradiation) must effectively eliminate microorganisms without altering the material’s properties or leaving toxic residues.

Biocompatibility testing is a rigorous, multi-stage process involving in vitro (cell culture), ex vivo, and in vivo (animal models) studies, as well as clinical trials, adhering to international standards (e.g., ISO 10993 series) [26].

4.2. Biodegradation

Biodegradation is the process by which a biomaterial is gradually broken down and resorbed by biological systems in vivo. For many applications, particularly in regenerative medicine, controlled biodegradation is not merely desirable but absolutely crucial. It allows for the temporary provision of mechanical support or a scaffold for tissue regeneration, which is then gradually replaced by newly formed native tissue, eliminating the need for a second surgery to remove the implant and reducing the risk of long-term complications such as chronic inflammation or infection [16].

Mechanisms of Biodegradation:

- Hydrolytic Degradation: This is the most common mechanism for biodegradable polymers, where ester bonds (e.g., in PLA, PGA, PCL) are cleaved by water molecules, leading to a reduction in molecular weight and subsequent loss of mechanical integrity. The rate of hydrolysis is influenced by material chemistry, crystallinity, molecular weight, and the local physiological pH [16]. Bioactive glasses also undergo hydrolytic degradation as part of their bioactivity mechanism, releasing ions and forming a silica gel layer [10, 4].

- Enzymatic Degradation: Some polymers, especially natural ones like collagen or chitosan, are degraded by specific enzymes present in the body (e.g., collagenases, proteases, lysozyme). The presence and activity of these enzymes can vary significantly depending on the tissue and inflammatory state.

- Oxidative Degradation: Certain materials, particularly some polymers and metals, can undergo oxidative degradation initiated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by immune cells during inflammation. This can lead to chain scission and material breakdown.

- Phagocytosis: For particulate degradation products, macrophages and other phagocytic cells can engulf and metabolize the smaller fragments.

Importance of Controlled Biodegradation:

- Matching Degradation Rate with Tissue Regeneration: The ideal biodegradable scaffold should degrade at a rate synchronized with the rate of new tissue formation. If it degrades too quickly, the new tissue may not have sufficient time to mature and assume mechanical loads, potentially leading to construct collapse. If it degrades too slowly, it may impede full tissue regeneration, remain as a foreign body, and potentially cause chronic inflammation or stress shielding [16].

- Minimizing Adverse Byproducts: The degradation products must be non-toxic, non-inflammatory, and readily metabolized and excreted by the body. For instance, the acidic degradation products of some polyesters can transiently lower local pH, potentially causing localized inflammation or hindering cell activity.

- Mechanical Integrity Over Time: The material must maintain sufficient mechanical strength to bear loads during the initial healing phases before gradually transferring stress to the regenerating tissue. This is particularly challenging for load-bearing applications like bone scaffolds.

For the TrabeculeX Bioactive Matrix, controlled biodegradation is intrinsic to its function. As a bioactive glass-based scaffold, its surface ions are released upon implantation, initiating the bioactivity cascade that promotes bone formation. Concurrently, the glass structure itself undergoes a degree of dissolution and remodeling, allowing the growing bone to gradually replace the scaffold. This intricate balance between surface bioactivity and bulk degradation is crucial for the successful integration and long-term performance of such advanced regenerative scaffolds.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

5. Surface Modification and Topography

The interface between a biomaterial and its biological environment is arguably the most critical determinant of the implant’s success or failure. It is at this intricate boundary where the initial host response is orchestrated, dictating everything from protein adsorption and cell adhesion to subsequent tissue integration or rejection. Consequently, the meticulous control of a biomaterial’s surface properties—both its chemical composition and physical topography—has become a cornerstone of modern biomaterial engineering, particularly for devices designed to actively promote tissue regeneration like the TrabeculeX Bioactive Matrix.

5.1. The Critical Role of the Biomaterial Surface

When an implant enters the body, its surface is immediately exposed to physiological fluids. The very first event is the rapid adsorption of proteins from these fluids, forming a layer that mediates subsequent cellular interactions. Cells, unlike liquids or inert chemicals, do not ‘see’ the bulk properties of a material; they ‘feel’ and ‘sense’ its surface. The specific proteins adsorbed, their conformation, and the underlying surface characteristics (roughness, charge, hydrophobicity) influence how cells (e.g., osteoblasts, fibroblasts, immune cells) attach, spread, proliferate, differentiate, and express genes [6, 27].

5.2. Surface Chemistry Modifications

Modifying the chemical composition of a biomaterial surface aims to introduce specific functional groups, biological molecules, or enhance certain interactions without altering the bulk properties of the material. Common techniques include:

- Plasma Treatment: This technique uses a gas plasma to clean, activate, or deposit thin films on surfaces. It can introduce polar functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carboxyl) to make surfaces more hydrophilic, thereby enhancing protein adsorption and cell adhesion [28].

- Coating Techniques:

- Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD) and Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD): These methods are used to deposit thin, uniform layers of materials (e.g., titanium nitride, carbon) for improved wear resistance or biocompatibility.

- Sol-Gel Method: This wet chemical technique allows for the synthesis of ceramic coatings (e.g., hydroxyapatite, bioactive glass) at lower temperatures, often used to create osteoconductive surfaces on metallic implants [29].

- Grafting and Polymer Brushes: Attaching polymer chains (grafting) or creating dense layers of polymer chains (polymer brushes) onto a surface can impart specific properties, such as antifouling characteristics (to prevent protein adsorption and bacterial adhesion) or stimuli-responsive behavior [30].

- Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs): These highly ordered molecular assemblies form spontaneously on surfaces and can present specific chemical groups or biological ligands to interact with cells [31].

- Incorporation of Bioactive Molecules: This involves immobilizing peptides, growth factors (e.g., BMPs for bone regeneration), extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins (e.g., collagen, fibronectin), or drugs directly onto the material surface. These molecules act as specific signals to guide cell behavior, promoting desired processes like osteogenesis or angiogenesis [6]. For example, RGD (arginine-glycine-aspartic acid) peptides, found in ECM proteins, are commonly grafted onto surfaces to promote cell adhesion via integrin binding.

5.3. Surface Topography and Morphology

Beyond chemistry, the physical architecture of a biomaterial surface—its roughness, porosity, and the presence of micro- and nanoscale features—profoundly influences cellular responses. This concept is particularly relevant for materials like the TrabeculeX Bioactive Matrix, which boasts a ‘unique surface topography’ designed for optimal bone growth [3].

- Microscale Roughness: At the micro-level (typically 1-100 µm), surface roughness can significantly impact cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation. For instance, moderately roughened titanium surfaces are known to enhance osteoblast adhesion and promote osseointegration compared to smooth surfaces in dental and orthopedic implants. This is often achieved through sandblasting, acid etching, or anodization [32]. These features provide anchor points for cells and can influence the local stress environment.

- Nanoscale Features: Advances in nanotechnology have revealed the critical importance of features at the nanoscale (1-100 nm). Natural bone, for example, has a hierarchical structure with collagen fibrils and apatite nanocrystals. Mimicking these nanoscale features on biomaterial surfaces can precisely guide cell behavior. Nanotopography can influence focal adhesion formation, cytoskeletal organization, and even gene expression, promoting specific cell phenotypes (e.g., osteogenic differentiation) [33]. Techniques to achieve nanotopography include electrospinning (for nanofibers), anodization (for titania nanotubes), and lithography.

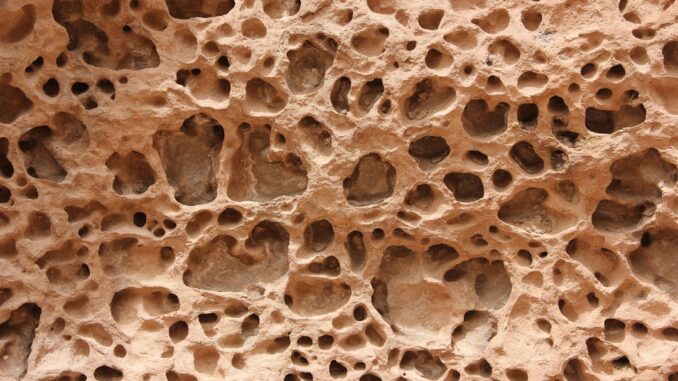

- Porous Structures: The presence of interconnected pores within a scaffold is vital for tissue ingrowth, nutrient transport, waste removal, and vascularization. The size, distribution, and interconnectivity of these pores are crucial parameters. For bone regeneration, typical pore sizes range from 100-500 µm to allow for osteoblast migration, vascular ingrowth, and new bone formation. A highly interconnected porous network ensures deep tissue penetration and avoids dead-end pores that could lead to necrotic regions [34].

5.4. The TrabeculeX Bioactive Matrix: An Example of Intelligent Surface Design

The TrabeculeX Bioactive Matrix, as a bioactive glass-based scaffold, embodies the confluence of beneficial material chemistry and sophisticated surface topography for optimal bone regeneration. While specific proprietary details are not publicly detailed, one can infer its design principles based on current biomaterial science:

- Bioactive Glass Core: The fundamental advantage lies in its bioactive glass composition, ensuring the characteristic ion release and subsequent formation of a bone-bonding hydroxyapatite layer [10, 4]. This chemical bioactivity is the primary driver for initiating osseointegration.

- Porous Trabecular Architecture: The term ‘TrabeculeX’ itself suggests a design that mimics the trabecular (spongy) bone structure. This implies a highly porous, interconnected internal architecture with optimized pore sizes. Such a structure serves as a three-dimensional scaffold, facilitating cell infiltration, vascularization, and widespread new bone formation throughout the implant volume [34]. The high surface area associated with a porous structure maximizes the contact points for bioactive glass-bone interaction.

- Micro/Nanoscale Topography: Beyond the macroscopic pores, it is highly probable that the surface of the TrabeculeX matrix incorporates specific micro- and nanoscale features. These features would be strategically designed to promote the attachment, spreading, proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation of bone cells (osteoblasts and mesenchymal stem cells). This could involve controlled roughness, specific surface patterns, or even nanoscale textures that guide the orientation and activity of bone-forming cells, thereby accelerating and enhancing bone regeneration [33].

- Biomimetic Approach: The overall design of TrabeculeX is likely a biomimetic approach, attempting to replicate the natural hierarchical structure and biological cues of native bone. By presenting both chemical signals (from bioactive glass dissolution) and physical signals (from optimized topography), the scaffold actively directs the host’s regenerative processes towards robust osteogenesis [1].

In essence, the TrabeculeX Bioactive Matrix represents an advanced ‘third-generation’ biomaterial where the synergy between inherent material bioactivity and deliberately engineered surface topography creates an environment uniquely conducive to rapid and strong bone regeneration, minimizing the fibrous encapsulation typically associated with less sophisticated implants.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

6. Medical Applications of Biomaterials

Biomaterials have permeated nearly every branch of medicine, offering solutions for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of diseases and injuries. Their diverse properties allow for tailored applications, transforming patient care and quality of life across a vast spectrum of medical specialties.

6.1. Orthopedics and Spinal Surgery

Orthopedics represents one of the largest and most mature application areas for biomaterials, primarily addressing the repair and replacement of bone, cartilage, ligaments, and tendons. The TrabeculeX Bioactive Matrix falls squarely within this domain, specifically for bone regeneration.

- Joint Replacements: Total hip and knee arthroplasties are among the most successful surgical procedures. Materials like titanium alloys and cobalt-chromium alloys are used for femoral stems and acetabular components, while UHMWPE or ceramic-on-ceramic systems form the articulating surfaces. Challenges include wear particle generation, aseptic loosening, and periprosthetic infection [11].

- Bone Plates, Screws, and Rods: Stainless steel and titanium alloys are extensively used for internal fixation of fractures, providing mechanical stability during the healing process. Biodegradable polymers (PLA, PGA) are increasingly employed for temporary fixation devices, eliminating the need for removal surgeries [9, 16].

- Spinal Implants: In spinal fusion surgeries, interbody fusion cages (often made of PEEK, titanium, or tantalum) are used to restore disc height and promote fusion between vertebrae. Bone graft substitutes, including bioactive glasses (like the material in TrabeculeX), hydroxyapatite, and calcium phosphates, are packed within these cages or used as standalone grafts to facilitate bone growth and spinal stability [35].

- Bone Grafts and Substitutes: For bone void filling, non-union repairs, or spinal fusion, a range of materials are used. Autografts (patient’s own bone) remain the gold standard but have donor site morbidity. Allografts (donor bone) carry risks of disease transmission and immune response. Synthetic bone graft substitutes, including the TrabeculeX Bioactive Matrix, bioactive glasses, calcium phosphates, and porous polymer scaffolds, offer predictable properties, unlimited supply, and tailored bioactivity to promote osteoconduction and sometimes osteoinduction [1, 14].

6.2. Cardiovascular Devices

Biomaterials are crucial for treating various cardiovascular diseases, from repairing damaged vessels to replacing failing heart valves.

- Vascular Grafts: Dacron (polyethylene terephthalate) and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) are widely used to replace or bypass diseased arteries. Their biocompatibility, mechanical strength, and ability to allow for a degree of tissue ingrowth make them suitable for large-diameter vessels [17]. Challenges remain in small-diameter vessel grafts due to thrombosis and intimal hyperplasia.

- Stents: These small mesh tubes are deployed to open stenosed arteries. Bare-metal stents (BMS, typically stainless steel or cobalt-chromium) provide mechanical scaffolding. Drug-eluting stents (DES) incorporate a polymer coating that slowly releases immunosuppressive or antiproliferative drugs to prevent restenosis. Bioresorbable stents, designed to degrade after their function is served, represent a promising future direction [36].

- Heart Valves: Mechanical heart valves (e.g., carbon composites, titanium) offer excellent durability but require lifelong anticoagulation. Bioprosthetic valves (e.g., porcine or bovine pericardial tissue, often glutaraldehyde-treated to reduce immunogenicity) have better hemodynamics but limited durability [37].

- Pacemakers and Defibrillators: The leads and encapsulation materials (silicones, polyurethanes) for these devices require excellent biocompatibility, flexibility, and insulation properties to ensure long-term functionality without triggering adverse immune responses.

6.3. Drug Delivery Systems

Biomaterials play a transformative role in achieving controlled and localized drug release, improving therapeutic efficacy while minimizing systemic side effects.

- Biodegradable Polymers: PLA, PGA, and their copolymers are extensively used to create microparticles, nanoparticles, films, and implantable depots that encapsulate drugs. The drug is released as the polymer degrades, allowing for sustained release over weeks or months, such as in hormonal implants or chemotherapy delivery [16].

- Hydrogels: These highly hydrated polymer networks can swell and encapsulate drugs. Their porous structure allows for drug diffusion, and their release kinetics can be tuned by crosslinking density and polymer chemistry. They are used for localized delivery in ophthalmology, cancer therapy, and regenerative medicine [38].

- Stimuli-Responsive Systems: ‘Smart’ biomaterials can release drugs in response to specific physiological cues, such as pH changes (e.g., in tumor microenvironments), temperature fluctuations, or the presence of specific enzymes, offering highly targeted therapies.

6.4. Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine

This field aims to create biological substitutes that restore, maintain, or improve tissue function. Biomaterials serve as crucial scaffolds that guide cell growth and differentiation.

- Scaffolds: Porous biomaterial scaffolds (polymers, ceramics, composites) provide a three-dimensional framework that mimics the extracellular matrix, offering attachment sites for cells, facilitating nutrient and waste exchange, and guiding tissue formation. The scaffold’s architecture, pore size, and mechanical properties are critical for directing the regeneration of various tissues, including bone, cartilage, skin, and neural tissue [34]. TrabeculeX exemplifies a scaffold designed specifically for bone regeneration.

- Cell Encapsulation: Biomaterials, particularly hydrogels, are used to encapsulate cells (e.g., pancreatic islets for diabetes, chondrocytes for cartilage repair) to protect them from the immune system and deliver them to target sites [21].

- Bioreactors: Biomaterials are often integrated into bioreactor systems to provide the necessary mechanical and biochemical cues for in vitro tissue development prior to implantation.

6.5. Ocular Implants

Biomaterials are fundamental to maintaining and restoring vision.

- Contact Lenses: Hydrogels and silicone hydrogels are widely used for their transparency, oxygen permeability, and comfort. They are designed to be soft, flexible, and biocompatible with the ocular surface [39].

- Intraocular Lenses (IOLs): Made from PMMA, silicone, or acrylic, IOLs replace the natural lens after cataract surgery, providing clear vision. Their excellent long-term optical clarity and biocompatibility are paramount.

- Glaucoma Shunts: Materials like silicone are used to create drainage devices that help regulate intraocular pressure in glaucoma patients.

6.6. Dental Applications

Biomaterials are essential for restorative and reconstructive dentistry.

- Dental Implants: Titanium and its alloys are the standard for dental implants due to their excellent osseointegration properties. Zirconia is also gaining popularity for aesthetic reasons [9].

- Fillings: Amalgams (silver, tin, copper, mercury alloy) have been largely replaced by composite resins (polymer matrix with ceramic fillers) and glass ionomer cements for their aesthetics and bonding capabilities.

- Crowns and Bridges: Ceramics (porcelain, alumina, zirconia), metals (gold alloys, nickel-chromium), and metal-ceramic combinations are used for their durability, aesthetics, and biocompatibility.

6.7. Wound Healing and Dermatological Applications

Biomaterials facilitate wound closure, promote healing, and protect damaged skin.

- Wound Dressings: Hydrogels, collagen sponges, chitosan films, and synthetic polymer membranes are used to maintain a moist wound environment, absorb exudate, prevent infection, and deliver healing agents.

- Skin Substitutes: Biodegradable polymer-collagen scaffolds seeded with dermal fibroblasts and epidermal keratinocytes can be used to treat severe burns and chronic wounds [18].

6.8. Neuro-biomaterials

This emerging field focuses on repairing and regenerating neural tissues.

- Nerve Guidance Conduits: Biodegradable polymers (e.g., PLA, PCL, collagen) are fabricated into tubular structures to bridge gaps in damaged peripheral nerves, guiding axonal regeneration [40].

- Neural Probes: Materials with high biocompatibility and electrical conductivity are used for brain-computer interfaces or deep brain stimulation. Challenges include chronic inflammation and fibrous encapsulation around the electrode tips.

This extensive range of applications underscores the profound and ever-growing impact of biomaterials in modern medicine, continually pushing the boundaries of what is surgically and therapeutically possible.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

7. Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the remarkable progress in biomaterial engineering, the field continues to grapple with significant challenges that impede optimal patient outcomes and limit the full potential of these advanced materials. Simultaneously, cutting-edge research is rapidly advancing, pointing towards exciting future directions that promise to overcome these hurdles and revolutionize medical treatments.

7.1. Enduring Challenges in Biomaterial Engineering

-

Infection and Biofilm Formation: One of the most persistent and devastating complications of implant surgery is infection. Bacteria can adhere to implant surfaces and form biofilms, highly resistant communities encased in an extracellular polymeric matrix [41]. These biofilms are notoriously difficult to eradicate with antibiotics and often necessitate implant removal, leading to costly revision surgeries and patient morbidity. Developing effective strategies to prevent biofilm formation remains a critical challenge.

-

Host Immune Response and Chronic Inflammation: While biomaterials are designed to be biocompatible, they are still perceived as foreign bodies by the immune system. This can trigger an undesirable host response, leading to chronic inflammation, fibrous encapsulation, and eventually implant failure [25]. Modulating the immune response, rather than simply suppressing it, towards a pro-regenerative phenotype is a complex biological puzzle.

-

Mechanical Mismatch and Stress Shielding: In load-bearing orthopedic applications, a significant disparity between the elastic modulus of the metallic implant and that of native bone can lead to stress shielding. The stiffer implant carries a disproportionate amount of the load, reducing mechanical stress on the surrounding bone. This can result in bone resorption (osteopenia) around the implant, ultimately leading to implant loosening and failure [9]. Designing materials with mechanical properties closely mimicking native tissues is an ongoing challenge.

-

Long-term Stability and Degradation Control: For permanent implants, ensuring long-term structural integrity and corrosion resistance over decades is crucial. For biodegradable implants, achieving precise control over the degradation rate to match the pace of tissue regeneration remains difficult. Uncontrolled or heterogeneous degradation can lead to premature mechanical failure, release of undesirable byproducts, or incomplete tissue integration [16].

-

Integration with Host Tissue: Achieving true, seamless integration where the implant is indistinguishable from native tissue is the ultimate goal, particularly for regenerative applications. While osseointegration in bone is well-established for some materials, integration with soft tissues (e.g., muscle, nerve, cartilage) is far more challenging due to differences in cellular composition, ECM architecture, and mechanical properties.

-

Regulatory Hurdles and Commercialization: The translation of novel biomaterial innovations from lab to clinic is often a lengthy, costly, and complex process. Stringent regulatory requirements for safety and efficacy necessitate extensive pre-clinical and clinical testing, which can be a significant barrier to commercialization for smaller enterprises and innovative, but unproven, materials.

7.2. Future Directions and Emerging Frontiers

The challenges outlined above are actively being addressed by cutting-edge research, driving several exciting future directions in biomaterial engineering:

-

Smart and Responsive Biomaterials: The next generation of biomaterials is envisioned to be ‘smart,’ meaning they can sense physiological changes (e.g., pH, temperature, enzyme activity, presence of pathogens) and respond dynamically. This could involve self-healing capabilities, triggered drug release, or even changes in mechanical properties [42]. For example, a wound dressing that releases antibiotics only when bacterial infection is detected, or a bone scaffold that releases growth factors only when bone healing slows.

-

Bioactive and Bioregenerative Materials: Moving beyond mere bioactivity, future materials aim to be truly bioregenerative. This involves not just promoting tissue growth but actively guiding the body’s intrinsic regenerative capacity. This includes materials that can recruit specific stem cells, modulate the local immune environment to favor regeneration over fibrosis, and deliver multiple biological cues in a spatiotemporally controlled manner [1]. The TrabeculeX Bioactive Matrix is an early exemplar of this trend, and future iterations will likely incorporate even more sophisticated biological signaling.

-

Advanced Manufacturing (e.g., 3D/4D Printing): Additive manufacturing techniques like 3D printing (bioprinting) are transforming the field by enabling the creation of patient-specific implants with highly complex, hierarchical architectures, precise pore sizes, and customized mechanical properties. 4D printing takes this a step further by creating structures that can change shape or function over time in response to external stimuli, opening avenues for dynamically adapting implants [43].

-

Nanobiomaterials: Engineering materials at the nanoscale offers unprecedented control over cell-material interactions. Nanoparticles can be used for targeted drug delivery and diagnostics. Nanofibers and nanostructured surfaces can mimic the native extracellular matrix, guiding cell behavior with high precision and enhancing tissue regeneration. For instance, creating bone scaffolds with nanometer-scale roughness to optimize osteoblast adhesion [33].

-

Immunomodulatory Biomaterials: A deeper understanding of immunomodulation is leading to the design of materials that can actively steer the immune response away from chronic inflammation and towards constructive tissue remodeling. This could involve incorporating immunomodulatory cytokines or designing surfaces that direct macrophage polarization towards a pro-healing (M2) phenotype [44].

-

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: AI and ML are being deployed to accelerate biomaterial discovery and design. These computational tools can predict material properties, optimize synthesis parameters, screen for biocompatibility, and even design novel material compositions based on desired biological outcomes, significantly reducing the time and cost of R&D [45].

-

Theranostics: This emerging field combines therapeutic agents with diagnostic capabilities within a single biomaterial system. For example, a nanoparticle could deliver a drug to a tumor while simultaneously providing imaging contrast for real-time monitoring of treatment efficacy.

These future directions highlight a shift towards more intelligent, personalized, and biologically active biomaterial solutions. The ongoing interdisciplinary collaboration between material scientists, engineers, biologists, and clinicians is crucial to navigating these complex frontiers and translating these innovations into improved patient care and truly regenerative therapies.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

8. Conclusion

The journey of biomaterials, from rudimentary ancient applications to the sophisticated ‘third-generation’ systems of today, reflects a profound evolution in our understanding of the intricate interplay between engineered materials and complex biological systems. The TrabeculeX Bioactive Matrix stands as a compelling testament to this progress, exemplifying how the judicious integration of bioactive glass chemistry with an intelligently designed, unique surface topography can profoundly enhance bone regeneration. Its ability to actively promote osteogenesis through a controlled biological response rather than passive integration marks a significant advancement in orthopedic regenerative medicine.

This report has systematically explored the foundational principles underpinning this dynamic field, from the historical milestones, including the seminal discovery of bioactive glass by L.L. Hench, to the diverse classifications of metals, ceramics, polymers, and composites. We have delved into the critical concepts of biocompatibility and controlled biodegradation, emphasizing their paramount importance in ensuring predictable host responses and facilitating seamless tissue integration. Furthermore, the detailed examination of surface modification and micro/nanoscale topography has illuminated how meticulous surface engineering dictates cellular behavior and, ultimately, the success of the implant. The expansive array of medical applications across orthopedics, cardiovascular health, drug delivery, tissue engineering, and beyond underscores the pervasive and indispensable role of biomaterials in modern healthcare.

While significant challenges persist—ranging from infection and immune modulation to mechanical mismatch and regulatory complexities—the future of biomaterial engineering is vibrant and promising. The advent of ‘smart’ and responsive materials, advanced manufacturing techniques like 3D/4D printing, nanobiomaterials, and the strategic application of artificial intelligence are poised to overcome existing limitations. These emerging frontiers promise the development of next-generation implants and therapeutic devices that are not only highly effective but also personalized, adaptive, and truly bioregenerative. The continuous pursuit of materials that can more intimately and effectively integrate with biological systems will undoubtedly lead to unprecedented improvements in patient outcomes, further solidifying biomaterials as a cornerstone of medical innovation for decades to come.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

References

- Hench, L. L., & Polak, J. M. (2002). Third-generation biomedical materials. Science, 295(5557), 1014-1017.

- Ratner, B. D., Hoffman, A. S., Schoen, F. J., & Lemons, J. E. (Eds.). (2013). Biomaterials Science: An Introduction to Materials in Medicine (3rd ed.). Elsevier.

- Xenco Medical. (2024). TrabeculeX Continuum. Orthopedic Design and Technology. Retrieved from https://www.orthopedicdesign.org/technology/trabeculex-continuum

- Bioactive Glass S53P4. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bioactive_glass_S53P4

- Bioceramic. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bioceramic

- Surface Modification of Biomaterials with Proteins. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Surface_modification_of_biomaterials_with_proteins

- Classification and Medical Applications of Biomaterials–A Mini Review. (2022). Bio Integration, 4(2), 54–61. Retrieved from https://bio-integration.org/10-15212/bioi-2022-0009/

- Temenoff, J. S., & Mikos, A. G. (2008). Biomaterials: The Intersection of Biology and Materials Science. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Niinomi, M. (2000). Mechanical properties of biomedical titanium alloys. Materials Science and Engineering: A, 243(1-2), 231-236.

- Hench, L. L. (1991). Bioceramics: from concept to clinic. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 74(7), 1487-1510.

- Kurtz, S. M. (2009). The UHMWPE Handbook: Ultra-High Molecular Weight Polyethylene in Total Joint Replacement and Medical Devices. Academic Press.

- Piconi, C., & Macchetta, A. (2000). Zirconia as a biomaterial. Biomaterials, 21(9), 1019-1024.

- Suchanek, W., & Yoshimura, M. (1998). Processing and properties of hydroxyapatite-based biomaterials for use as hard tissue replacements. Journal of Materials Research, 13(1), 94-117.

- Bohner, M. (2000). Calcium orthophosphates in medicine: from ceramic to bone substitutes. Materials Today, 3(9), 24-30.

- Lewis, G. (1997). Properties of acrylic bone cement: state of the art. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research, 38(2), 155-182.

- Gunatillake, P. A., & Adhikari, R. (2003). Biodegradable synthetic polymers for tissue engineering. European Cells and Materials, 5, 1-16.

- Clowes, A. W., & Kirkman, T. R. (1995). Endothelialization of Dacron and ePTFE arterial prostheses. Journal of Vascular Surgery, 21(1), 170-176.

- Lynn, A. K., & Nema, S. (2005). Collagen-based scaffolds for tissue engineering. Trends in Biotechnology, 23(1), 5-13.

- Fallacara, A., Baldini, E., Manzi, L., & Bocchietto, E. (2018). Hyaluronic acid in medical and cosmetic applications. In Biomaterials Science (pp. 589-607). Springer, Cham.

- Muzzarelli, R. A. A. (1996). Chitin and Chitosan in Drug Delivery. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 18(1), 1-22.

- Lee, K. Y., & Mooney, D. J. (2001). Alginate: Properties and biomedical applications. Progress in Polymer Science, 26(9), 1783-1820.

- Vepari, C., & Kaplan, D. L. (2007). Silk as a biomaterial. Progress in Polymer Science, 32(8-9), 991-1007.

- Rezwan, K., Chen, Q. Z., Blaker, J. J., & Boccaccini, A. R. (2006). Biodegradable and bioactive polymer/inorganic composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials, 27(18), 3413-3431.

- Zhang, Y., & Zhang, M. (2001). Synthesis and characterization of biodegradable polymer/hydroxyapatite composites. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research, 55(3), 304-310.

- Williams, D. F. (2008). On the mechanisms of biocompatibility. Biomaterials, 29(29), 2941-2953.

- International Organization for Standardization. (2018). ISO 10993-1: Biological evaluation of medical devices – Part 1: Evaluation and testing within a risk management process.

- Anselme, K., & Giavaresi, G. (2006). Biomaterials, cells and tissues interface. Biomaterials, 27(18), 3422-3430.

- Vesel, A. (2018). Plasma surface modification of biomaterials for biomedical applications. Materials Science and Engineering: C, 86, 178-189.

- Kokubo, T., & Takadama, H. (2006). How useful is SBF in predicting in vivo bone bioactivity?. Biomaterials, 27(15), 2907-2915.

- Huck, W. T. S. (2004). Polymer brushes as an active template for cell culture. Nature Materials, 3(2), 79-81.

- Love, J. C., Estroff, L. A., Kriebel, J. K., Nuzzo, G., & Whitesides, G. M. (2005). Self-assembled monolayers of thiols on gold and silver. Chemical Reviews, 105(3), 1103-1169.

- Wennerberg, A., & Albrektsson, T. (2009). Effects of surface roughness on cellular response. International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants, 24, 7-15.

- Salvi, F., & Di Silvio, L. (2016). Nanotechnology in bone tissue engineering: state of the art. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 104(2), 488-501.

- Karageorgiou, V., & Kaplan, D. (2005). Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials, 26(27), 5474-5491.

- Vaccaro, A. R. (2002). The use of allograft and autograft in lumbar interbody fusion. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 394, 21-30.

- Serruys, P. W., Onuma, Y., Ormiston, J. A., De Bruyne, B., Fearon, W. F., Gregson, J., … & Windecker, S. (2016). A bioresorbable everolimus-eluting scaffold versus a metallic everolimus-eluting stent for the treatment of predominantly de novo coronary artery lesions: a randomised, blinded, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. The Lancet, 387(10014), 167-177.

- Schoen, F. J., & Levy, R. J. (2001). Calcification of cardiovascular tissues: pathogenesis, prevention, and management. Circulation, 103(14), 1957-1965.

- Peppas, N. A., Bures, J., Leobandung, W., & Ichikawa, H. (2000). Hydrogels in pharmaceutical formulations. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, 50(1), 27-46.

- Efron, N., & Morgan, P. B. (2017). The effect of wearing contact lenses on the prevalence of corneal staining. Contact Lens & Anterior Eye, 40(6), 390-394.

- Navarro, X., Vivo, M., & Valero-Cabré, A. (2019). Neural guidance conduits for peripheral nerve regeneration. Biomaterials, 198, 145-154.

- Donlan, R. M., & Costerton, J. W. (2002). Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 15(2), 167-193.

- Tibbitt, M. W., & Anseth, K. S. (2012). Hydrogels as tunable matrices for the study of cell behavior. Biomaterials, 33(23), 5991-600 tibbit.19.

- Mironov, V., Boland, T., Markwald, T. W., & Stevens, P. A. (2003). Organ printing: technologies and future applications. Trends in Biotechnology, 21(4), 157-160.

- Brown, B. N., Badylak, S. F., & Ratner, B. D. (2015). Immunomodulatory biomaterials: a new paradigm for tissue engineering. Trends in Biotechnology, 33(5), 241-248.

- Reker, D., & Schneider, G. (2020). Machine learning for the design of therapeutic biomaterials. Trends in Biotechnology, 38(9), 947-957.

The discussion of surface modification and topography is particularly insightful. The potential to optimize cellular response through controlled micro/nanoscale features seems incredibly promising for enhancing tissue integration and regeneration in vivo.

Thanks for pointing that out! The ability to tailor the micro/nanoscale topography of biomaterials really opens up some exciting possibilities. We’re seeing more research into how specific surface patterns can directly influence cell behavior, which could lead to even better tissue regeneration in the future. What are your thoughts on the challenges involved in translating these lab-scale findings to real-world applications?

Editor: MedTechNews.Uk

Thank you to our Sponsor Esdebe

“Bioactive glass orchestrating robust osteogenesis”? Sounds like something out of a sci-fi movie! I’m curious, with all this focus on *bio*activity, are we also considering the potential for *unintended* biological interactions? Could we accidentally create a scaffold that attracts, say, space algae? #biomaterials #spacealgae #justasking

That’s a great question! The potential for unintended interactions is definitely something we consider. While space algae might be a stretch, we focus on ensuring the bioactive glass promotes bone cell growth specifically, and doesn’t negatively affect other cells or tissues in the body. Further research will help us refine these interactions even more.

Editor: MedTechNews.Uk

Thank you to our Sponsor Esdebe

This is a very comprehensive overview of biomaterials! The discussion of medical applications is particularly striking, demonstrating the breadth of impact across various specialties. I’m curious about how personalized medicine, driven by advances in 3D printing and material design, can further revolutionize treatments in areas like reconstructive surgery and customized implants.

Thanks! I completely agree about personalized medicine. The ability to 3D print patient-specific implants with tailored material properties has huge potential. Think about the possibilities for craniofacial reconstruction or customized joint replacements that perfectly match a patient’s anatomy and biomechanical needs. It’s a really exciting area of development!

Editor: MedTechNews.Uk

Thank you to our Sponsor Esdebe

This is a very thorough report! Considering the challenges with infection, how might future biomaterials incorporate antimicrobial properties (e.g., through surface coatings or controlled release of antimicrobial agents) while maintaining biocompatibility and promoting tissue integration?

That’s an excellent point! Future strategies could involve incorporating antimicrobial peptides directly into the biomaterial or using surface coatings that release silver ions. Balancing antimicrobial efficacy with maintaining a healthy environment for tissue growth is definitely a key area of focus in current research. Thanks for the insightful question!

Editor: MedTechNews.Uk

Thank you to our Sponsor Esdebe

Given the discussion of infection as a challenge, could you elaborate on the most promising strategies for preventing bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation on biomaterial surfaces, and how these methods might impact long-term biocompatibility?

That’s a really important question! Some of the most promising strategies involve modifying the surface with antimicrobial coatings or incorporating nanoparticles that disrupt bacterial membranes. A key consideration is to ensure these methods don’t negatively impact the body’s own cells and hinder long-term tissue integration. It is a balancing act!

Editor: MedTechNews.Uk

Thank you to our Sponsor Esdebe

“Smart” biomaterials that respond to the body’s signals, eh? So, like tiny biomaterial butlers sensing my needs? Just imagine a bone implant that releases pain meds *before* I even feel the ache. I’d tip my hat to that level of service… assuming I could feel it through the bone. What are the ethical implications?

That’s a fantastic analogy! The concept of a proactive bone implant delivering pain meds pre-emptively is really intriguing. Your point about the ethical considerations is critical. We need to carefully consider issues like patient autonomy and potential overuse as these technologies advance. It is a balance to make sure the application meets the need.

Editor: MedTechNews.Uk

Thank you to our Sponsor Esdebe

Considering the TrabeculeX matrix mimics trabecular bone, how is the pore size and interconnectivity optimized to promote vascularization and nutrient transport throughout the entire scaffold, ensuring uniform bone regeneration in vivo?