Abstract

Control algorithms represent the quintessential ‘brain’ of autonomous health systems, orchestrating complex physiological processes through the sophisticated integration of predictive modeling, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning (ML). This comprehensive research report meticulously dissects the intricate technical underpinnings of these algorithms, paying particular attention to their paramount capabilities in real-time data acquisition and processing, their dynamic adaptability to the nuanced physiology of individual patients, and their robust responsiveness to a myriad of varying conditions such as fluctuating physical activity levels, acute and chronic stress responses, and the diverse nutritional composition of meals. Beyond functional analysis, the report critically examines the substantial computational challenges inherently associated with the development, rigorous testing, and seamless implementation of these highly complex algorithms. It further elucidates the multi-faceted validation processes indispensable for ensuring their unequivocal safety, reliability, and clinical efficacy, alongside a thorough exploration of the profound ethical considerations that inevitably arise from the deployment of AI-driven intelligence within sensitive autonomous health systems. While the primary investigative context for this report is the advanced management of Type 1 diabetes (T1D) facilitated by artificial pancreas (AP) systems, the profound insights, detailed analyses, and extensive discussions presented herein are designed to transcend this specific application, offering broad applicability to the burgeoning landscape of AI integration across the wider spectrum of modern healthcare.

1. Introduction

Autonomous health systems, most prominently exemplified by advanced artificial pancreas (AP) systems, have rapidly emerged as genuinely transformative solutions for the precise and continuous management of chronic conditions such as Type 1 diabetes (T1D). These innovative systems are meticulously engineered to emulate and, in some respects, surpass the highly complex glucose-regulating functions of a healthy, physiological pancreas. This is achieved by ceaselessly monitoring real-time blood glucose (BG) levels and intelligently adjusting the delivery of insulin, and sometimes glucagon, to maintain metabolic homeostasis. At the very core of the functionality and efficacy of AP systems reside highly sophisticated control algorithms. These algorithms are the operational nexus, diligently processing continuous streams of real-time physiological data, learning from the idiosyncratic physiological responses of individual patients, and adaptively responding to a diverse array of physiological states and dynamic external factors that influence glucose metabolism. This report undertakes an exhaustive examination of these pivotal control algorithms, systematically addressing their profound technical complexities, the significant computational demands they impose, the stringent validation methodologies employed to ensure their safety and performance, and the pervasive ethical implications stemming from the profound integration of AI into the critical domain of healthcare. The journey towards achieving a fully autonomous AP system has been a long and arduous one, marked by significant technological breakthroughs in continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), advanced insulin pump technologies, and, crucially, the evolution of sophisticated control theory adapted for biological systems. Early attempts at closed-loop insulin delivery date back to the 1970s, but limitations in sensor technology and computational power confined these systems to laboratory settings. The advent of real-time CGM and more precise, smaller insulin pumps in the early 21st century paved the way for practical AP systems, making the dream of automated glucose control a tangible reality for millions living with T1D (Bellazzi et al., 2001).

2. Control Algorithms in Autonomous Health Systems

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

2.1 Role and Functionality

Control algorithms in autonomous health systems are the principal agents responsible for the intricate task of interpreting continuous physiological data streams and executing precise, real-time decisions to meticulously regulate specific bodily functions. In the highly specialized context of AP systems, these algorithms are tasked with continuously monitoring blood glucose levels, predicting future glucose trajectories, and dynamically adjusting the delivery of insulin (and in some bi-hormonal systems, glucagon) to maintain blood glucose within a predefined, therapeutically optimal target range. The performance, robustness, and reliability of these algorithms are not merely important but absolutely crucial, as their operational characteristics directly and profoundly impact patient health outcomes, significantly reduce the burden of disease management, and substantially enhance the overall quality of life for individuals living with T1D. The objective is not just to prevent acute hyperglycemia (high blood sugar) and hypoglycemia (low blood sugar), which can be immediately life-threatening, but also to minimize glucose variability and maintain optimal glucose levels over prolonged periods, thereby reducing the risk of long-term diabetes complications such as retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy. This necessitates a delicate balance: providing enough insulin to counteract carbohydrate intake and basal metabolic needs, while simultaneously avoiding an over-delivery that could lead to dangerous hypoglycemia.

The functionality of these algorithms hinges on a closed-loop control paradigm, where a sensor (e.g., CGM) measures a physiological variable, a controller (the algorithm) processes this data and determines an action, and an actuator (e.g., insulin pump) executes that action. This feedback loop is continuous, allowing for dynamic adjustments in response to changing physiological states and external perturbations. Key metrics for evaluating the effectiveness of AP systems and their underlying algorithms include: Time In Range (TIR), typically defined as glucose levels between 70-180 mg/dL (3.9-10.0 mmol/L); Time Below Range (TBR), usually <70 mg/dL; and Time Above Range (TAR), usually >180 mg/dL. Reducing hypoglycemia, often the most feared complication for individuals with T1D, is a paramount objective. Furthermore, the algorithms must effectively manage challenges such as varying insulin sensitivity, unpredictable absorption rates of carbohydrates, the delayed action of insulin, and the confounding effects of exercise and stress.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

2.2 Types of Control Algorithms

The development of control algorithms for AP systems has evolved significantly, incorporating diverse methodologies to address the inherent complexities of glucose metabolism. Each type possesses distinct advantages and inherent limitations:

2.2.1 Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) Control

PID control stands as one of the oldest and most widely adopted control strategies in engineering, known for its relative simplicity and robustness in many industrial applications. In the context of AP systems, a PID controller adjusts insulin delivery based on the real-time error between the current continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) reading and the desired target glucose level. This error signal is processed by three distinct components:

- Proportional (P) term: This component generates an insulin dose proportional to the current error. A larger error leads to a larger immediate response. While offering quick correction, an overly aggressive P-term can lead to oscillations.

- Integral (I) term: This term accumulates past errors over time. It helps eliminate persistent, steady-state errors (e.g., a consistently slightly elevated glucose level) that the proportional term might not fully address. However, an overly aggressive I-term can lead to ‘integral windup,’ where the controller accumulates a large error even when the system is saturated, causing overshoot.

- Derivative (D) term: This component responds to the rate of change of the error. It provides an anticipatory action, attempting to dampen oscillations and improve transient response by reacting to impending changes. For example, if glucose levels are rapidly rising, the D-term can increase insulin delivery proactively. However, it is highly sensitive to noise in the sensor data.

While straightforward to implement, standard PID controllers exhibit significant limitations in the highly dynamic and complex physiological environment of glucose metabolism. They struggle to account for the inherent delays in insulin absorption and action (which can be 1-2 hours) and the variable digestion and absorption rates of carbohydrates from meals. PID controllers are fundamentally reactive rather than proactive, often leading to suboptimal glucose control, especially around meals or during exercise. Advanced variations, such as gain-scheduled PID or adaptive PID, attempt to mitigate these issues by dynamically adjusting the PID parameters based on factors like current glucose levels, insulin on board (IOB), or meal announcements, thereby providing some degree of personalization and anticipatory capability. Despite these enhancements, their fundamental inability to predict future glucose trends based on a physiological model limits their ultimate performance in comparison to more advanced model-based strategies (Bequette, 2013).

2.2.2 Model Predictive Control (MPC)

Model Predictive Control (MPC) represents a sophisticated, model-based control strategy that has become a cornerstone in the development of modern AP systems due to its ability to handle complex system dynamics, constraints, and delays. Unlike reactive PID, MPC is inherently anticipatory. It operates by utilizing a mathematical model of the patient’s glucose dynamics to predict future glucose levels over a specified ‘prediction horizon’ (e.g., the next 2-4 hours). Based on these predictions, the MPC algorithm then calculates an optimal sequence of insulin doses over a ‘control horizon’ (a shorter period within the prediction horizon) that minimizes a predefined cost function, while adhering to various physiological and safety constraints.

Key characteristics of MPC for AP systems:

- Predictive Capability: The core strength of MPC lies in its ability to predict how current and future insulin deliveries, along with anticipated disturbances (e.g., announced meals, exercise), will affect glucose levels. This allows the system to proactively deliver insulin before glucose rises significantly from a meal, or reduce basal insulin to prevent hypoglycemia during anticipated exercise.

- Mathematical Model: MPC relies on a robust physiological model that captures the dynamics of glucose absorption, insulin pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, and their interaction. Common models include compartment models (e.g., the Hovorka model, Sorensen model, or Bergman minimal model), which describe how glucose and insulin move between different bodily compartments (blood, interstitial fluid, subcutaneous tissue). These models are often personalized using patient-specific parameters (e.g., insulin sensitivity, carbohydrate-to-insulin ratio).

- Optimization Problem: At each control interval, MPC solves an online optimization problem. The cost function typically aims to minimize the deviation from the target glucose range, minimize glucose variability, and minimize hypoglycemia risk, often penalized more heavily than hyperglycemia. Constraints include limits on insulin delivery rates (e.g., maximum bolus, minimum basal rate), ensuring physiological safety.

- Receding Horizon Principle: Only the first computed insulin dose from the optimal sequence is applied. Then, at the next sampling interval (e.g., every 5 minutes), new CGM data becomes available, the prediction horizon slides forward, and the optimization problem is re-solved. This ‘receding horizon’ approach allows the system to adapt to unpredicted disturbances and model inaccuracies.

Advantages: MPC offers superior control quality, particularly in managing meals and preventing hypoglycemia by accounting for insulin delays and predicting future glucose excursions. It can explicitly incorporate information like carbohydrate intake and physical activity as feedforward inputs, significantly enhancing its anticipatory capabilities. Examples include the Medtronic MiniMed 780G system and many research prototypes (Sonzogni et al., 2024).

Challenges: MPC requires accurate physiological models, which are complex to develop and personalize due to high inter- and intra-patient variability. The computational load of solving the optimization problem in real-time on embedded devices can be substantial, requiring efficient algorithms and hardware. Robustness to model inaccuracies and unmeasured disturbances (e.g., stress, illness) remains an ongoing research area (Chen et al., 2020).

2.2.3 Fuzzy Logic (FL)

Fuzzy Logic (FL) systems offer an alternative control paradigm that moves away from precise mathematical models towards human-like reasoning, particularly useful when dealing with imprecise, uncertain, or qualitative information. This approach is well-suited for biological systems where exact models are difficult to derive or parameters are highly variable.

Key concepts in FL for AP systems:

- Fuzzy Sets: Instead of crisp true/false values, FL uses fuzzy sets where elements can have degrees of membership. For instance, ‘glucose is high’ is not just true or false, but glucose can be ‘partially high’ or ‘very high’ to different degrees.

- Linguistic Variables: Physiological states are described using linguistic terms (e.g., ‘glucose is rising fast’, ‘insulin on board is moderate’, ‘carbohydrate intake is large’). These terms are mapped to fuzzy sets.

- Rule Base: The core of an FL system is a set of ‘if-then’ rules, often derived from expert medical knowledge or clinical heuristics. For example: ‘IF glucose is high AND glucose is rising fast AND insulin on board is low THEN increase insulin delivery significantly.’

- Fuzzy Inference Engine: This engine processes the input data using the rule base to determine the degree to which each rule applies.

- Defuzzification: The fuzzy output (e.g., ‘insulin delivery should be moderately increased’) is converted into a crisp, quantifiable insulin dose that the pump can deliver.

Advantages: FL systems are robust to noisy sensor data and variability in patient responses. They can incorporate expert knowledge intuitively and are often easier to understand and debug than complex mathematical models. They perform well in situations where precise models are unavailable or computationally expensive.

Challenges: Developing and tuning a comprehensive rule base can be time-consuming, and the system’s stability and optimality are not as formally guaranteed as with model-based approaches. They may lack the strong predictive power of MPC unless combined with other techniques.

2.2.4 Reinforcement Learning (RL)

Reinforcement Learning (RL) represents a powerful paradigm where an ‘agent’ (the control algorithm) learns optimal control policies by interacting with an ‘environment’ (the patient’s physiological system) over time, receiving ‘feedback’ in the form of rewards or penalties. The goal of the RL agent is to maximize its cumulative reward.

Key components of RL for AP systems:

- Agent: The insulin delivery algorithm.

- Environment: The patient’s glucose-insulin system, including food intake, activity, and other factors.

- State: A representation of the current physiological condition (e.g., current glucose, rate of change of glucose, insulin on board, recent carbohydrate intake).

- Action: The decision made by the agent (e.g., change in basal insulin rate, bolus delivery).

- Reward: A numerical signal indicating the desirability of the current state or the consequence of an action (e.g., a high positive reward for glucose in target range, a large negative penalty for hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia).

- Policy: The strategy the agent learns, mapping states to actions that maximize future rewards.

RL algorithms, such as Q-learning, SARSA, or more advanced deep reinforcement learning (DRL) techniques, can adapt to individual patient responses and continuously improve their control strategies over time without explicit programming of rules or models. They learn optimal policies through trial and error, often in simulated environments before deployment. Model-based RL explicitly learns a model of the environment to plan, while model-free RL learns directly from experience.

Advantages: RL holds immense promise for personalization, as it can theoretically learn highly individualized and adaptive control strategies that account for unique metabolic responses and lifestyle patterns. It can handle unmodeled disturbances and learn complex, non-linear relationships. It offers a path towards truly autonomous and continuously self-optimizing systems (Tanzanakis & Lygeros, 2023).

Challenges: A major concern in healthcare is safety; allowing an RL agent to ‘explore’ potentially unsafe actions in a real patient is unacceptable. This necessitates extensive simulation-based training, safe exploration strategies, and robust safety layers. RL can also be data-intensive, requiring vast amounts of interaction data for effective learning. The ‘black box’ nature of complex RL policies can make them difficult to interpret or explain, posing challenges for regulatory approval and clinical adoption.

2.2.5 Hybrid and Advanced Approaches

Many state-of-the-art AP systems leverage hybrid approaches, combining the strengths of different control strategies. For instance:

- MPC with AI Enhancements: An MPC framework might use a machine learning model (e.g., neural network) for more accurate glucose prediction or to adapt model parameters in real-time (Chen et al., 2020).

- Fuzzy Logic-tuned MPC: Fuzzy logic can be used to tune the parameters of an MPC controller based on qualitative patient states, or to handle meal announcements and exercise in a more robust manner.

- RL for Parameter Tuning: RL could be employed to fine-tune the gains of a PID controller or the parameters of an MPC model for individual patients, offering a safer way to incorporate learning.

Furthermore, the integration of deep learning for glucose prediction from CGM data and other physiological markers is a growing area. Neural networks excel at pattern recognition in large datasets and can provide highly accurate short-term glucose forecasts, which are crucial for feedforward control in AP systems.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

2.3 Data Processing and Adaptation

The efficacy and safety of control algorithms in autonomous health systems are inextricably linked to their ability to process vast quantities of diverse, real-time data inputs and their capacity to adapt intelligently to individual physiological nuances. This sophisticated data management forms the bedrock for personalized and effective closed-loop control.

2.3.1 Real-Time Data Inputs

Modern AP systems typically ingest a rich tapestry of data streams, which are continuously fed into the control algorithms:

- Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) Readings: These are the primary feedback signals, providing interstitial glucose concentrations typically every 1-5 minutes. The accuracy, latency, and reliability of CGM sensors (e.g., Dexcom, Abbott Freestyle Libre) are paramount for safe and effective AP operation (Wikipedia contributors, 2024, ‘Dexcom CGM’). The rate of change of glucose, along with its absolute value, is a critical input.

- Insulin On Board (IOB): This crucial metric quantifies the amount of active insulin remaining in the body from previous boluses or basal deliveries. Accurately tracking IOB is essential to avoid insulin stacking, which can lead to severe hypoglycemia. The algorithm must account for the pharmacokinetic profile of the rapid-acting insulin used.

- Insulin Delivery History: Records of all previous insulin boluses (meal and correction) and basal rates provide a comprehensive picture of the insulin administered.

- Carbohydrate Intake (Meal Announcements): Patients typically input estimated carbohydrate counts for upcoming meals. While this is often the largest source of variability, algorithms are increasingly developed to handle unannounced or miscalculated meals (the ‘meal robustness’ challenge). Advanced systems might learn to estimate carbohydrate absorption profiles.

- Physical Activity/Exercise Data: Data from activity trackers (e.g., accelerometers, heart rate monitors) or patient self-reporting helps the algorithm anticipate increased insulin sensitivity and potential drops in glucose, allowing for pre-emptive basal insulin reduction or temporary target glucose adjustments. This is critical for preventing exercise-induced hypoglycemia.

- Other Patient-Reported Information: This can include stress levels, illness, sleep patterns, or temporary basal rate adjustments made by the user, all of which influence glucose dynamics.

- System Status: Battery levels, pump occlusion alerts, sensor expiry, and communication status are also monitored for safety and reliability.

2.3.2 Personalization and Adaptive Learning

One of the most significant advancements in AP algorithms is their capacity for personalization and adaptive learning, moving beyond a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach. Human physiology, especially in T1D, is inherently variable, influenced by genetics, lifestyle, age, stress, hormones, and co-morbidities. Algorithms must account for these individual differences to optimize glucose control.

- Parameter Identification: For model-based controllers like MPC, key physiological parameters (e.g., insulin sensitivity factor, carbohydrate-to-insulin ratio, insulin action duration) can be estimated and continuously refined based on historical glucose and insulin data. This can be done offline (e.g., during setup) or adaptively in real-time.

- Learning from Historical Data: Algorithms analyze long-term trends in patient data (glucose responses to meals, exercise, basal insulin) to refine control strategies. For instance, if a patient consistently experiences post-meal hyperglycemia despite sufficient meal boluses, the algorithm might suggest an adjustment to their carbohydrate ratio or pre-bolus timing.

- Real-time Adaptation: The system constantly adjusts its insulin delivery based on the very latest CGM readings and predicted trends. For example, if glucose is trending downwards rapidly, the system will temporarily reduce or suspend basal insulin, even if it’s within the target range, to preempt hypoglycemia.

- Rule-based Customization: Some systems allow for user-defined target glucose ranges, aggression levels, or specific settings for different times of day (e.g., tighter control overnight). This combines algorithmic intelligence with patient preferences.

- Machine Learning for Prediction: Beyond traditional physiological models, machine learning models (e.g., recurrent neural networks, support vector machines) can be trained on individual patient data to provide highly accurate, short-term glucose predictions. These predictions can then be fed into an MPC or other control strategy for enhanced anticipatory control.

This continuous personalization and adaptation significantly enhance the precision and effectiveness of insulin delivery, dramatically reducing the risks of both hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia and alleviating the immense mental burden of constant self-management for patients (Wikipedia contributors, 2024, ‘Automated insulin delivery system’). Systems like OpenAPS (Open-Source Artificial Pancreas System) have demonstrated the power of community-driven, personalized algorithms, allowing users a high degree of customization and insight into their control logic (Wikipedia contributors, 2024, ‘OpenAPS’).

3. Computational Challenges

The development and deployment of control algorithms for autonomous health systems, particularly AP systems, are fraught with significant computational challenges that demand innovative solutions in hardware, software, and systems engineering.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

3.1 Real-Time Data Processing

The requirement for real-time processing of physiological data is arguably the most fundamental and demanding computational constraint on AP systems. Unlike many industrial control systems that operate on relatively slow processes, biological systems, especially glucose metabolism, can change rapidly, necessitating swift and accurate intervention.

- High-Frequency Data Streams: CGMs typically transmit data every 1-5 minutes. The algorithm must continuously ingest, filter (to reduce noise), and process these readings. Each new data point triggers a complex chain of calculations, predictions, and optimization routines.

- Low Latency Requirements: Decisions about insulin delivery must be made within seconds of receiving new sensor data. Delays can lead to overshoots (hyperglycemia) or undershoots (hypoglycemia) due to the inherent lags in insulin action and glucose dynamics. For instance, if a rapid glucose drop is detected, the algorithm must halt insulin delivery almost instantly.

- Computational Intensity of Advanced Algorithms: Algorithms like Model Predictive Control (MPC) involve solving complex optimization problems (often quadratic programming or non-linear programming) at each control interval. These problems can be computationally intensive, especially with detailed physiological models and long prediction horizons. Reinforcement Learning (RL) agents also require significant processing for policy evaluation and updates.

- Limited Resources of Embedded Devices: AP systems typically run on small, battery-powered embedded devices (e.g., insulin pumps, smartphones). These devices have limited processing power, memory, and energy budgets. Algorithms must be highly optimized for efficiency, minimizing computational cycles and power consumption to extend battery life and ensure smooth operation.

- Error Handling and Robustness: Beyond raw computation, the system must robustly handle noisy or missing sensor data, communication dropouts, and other anomalies without compromising patient safety. This involves sophisticated data imputation techniques and fail-safe mechanisms.

Meeting these real-time demands necessitates highly efficient algorithm design (e.g., using sparse matrix solvers, pre-compilation, fixed-point arithmetic), optimized software architectures, and carefully selected low-power, high-performance microcontrollers or System-on-Chips (SoCs).

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

3.2 Model Complexity and Personalization

Developing accurate and robust models of glucose dynamics for AP systems presents formidable computational and theoretical challenges, particularly when aiming for high degrees of personalization.

- Physiological Complexity: Glucose metabolism is a highly non-linear, multi-faceted process influenced by numerous factors beyond insulin and carbohydrates, including hormones (e.g., glucagon, cortisol, adrenaline), physical activity, stress, illness, and sleep. Creating models that accurately capture these interactions without becoming computationally intractable is extremely difficult.

- Inter- and Intra-Individual Variability: There is significant variability in insulin sensitivity, carbohydrate absorption rates, and glucose response profiles between individuals. Furthermore, an individual’s parameters can change significantly within a day or over longer periods (e.g., due to illness, menstrual cycle, weight changes, changes in fitness). A static model is insufficient.

- Model Identification: Personalizing models requires extensive data collection and sophisticated parameter identification techniques. This often involves solving inverse problems, where model parameters are estimated from observed glucose and insulin data. These processes can be computationally intensive and susceptible to noise and data scarcity.

- Robustness to Unmodeled Disturbances: Any physiological model is an approximation. Algorithms must be robust to factors that are not explicitly modeled or are unmeasurable (e.g., a stressful event leading to unexpected glucose rise). This often involves robust control techniques, which add computational overhead.

- Computational Cost of Complex Models: More physiologically detailed models typically involve more states, parameters, and non-linear equations, significantly increasing the computational burden for prediction and optimization within an MPC framework. There’s a constant trade-off between model accuracy/detail and computational feasibility.

Advanced techniques such as adaptive filtering, online parameter estimation, and machine learning models for dynamic parameter updates are employed to address these challenges, but they introduce their own computational overheads.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

3.3 System Integration

Integrating the control algorithms with diverse hardware components and ensuring their harmonious, reliable operation constitutes another major computational and engineering hurdle.

- Heterogeneous Hardware: An AP system typically comprises a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), an insulin pump, and often a controller device (e.g., a dedicated handset or a smartphone). These components are often from different manufacturers, using proprietary communication protocols and data formats.

- Communication Protocols: Ensuring seamless, secure, and reliable communication between these devices (e.g., via Bluetooth Low Energy, ANT+) is crucial. This involves managing pairing, maintaining stable connections, handling disconnections gracefully, and ensuring data integrity and authenticity. Each communication event consumes processing power and battery.

- Data Synchronization and Timestamping: All data streams (CGM readings, insulin delivery commands, patient inputs) must be precisely timestamped and synchronized to avoid timing errors that could lead to incorrect control actions. This is particularly challenging in distributed systems where components may have independent clocks.

- User Interface (UI) Integration: The algorithm’s decisions must be effectively communicated to the patient through an intuitive and informative user interface. This involves rendering real-time glucose graphs, displaying IOB, pump status, and providing clear alerts. Developing responsive and power-efficient UIs on embedded devices adds to the computational load.

- Cybersecurity: As networked medical devices, AP systems are potential targets for cyberattacks. Protecting the integrity and confidentiality of physiological data and ensuring that insulin delivery commands cannot be maliciously altered requires robust encryption, authentication, and security protocols at every integration point. This adds significant computational overhead for cryptographic operations.

- Fault Tolerance and Redundancy: The system must be designed with fault-tolerant mechanisms. What happens if a sensor fails? If communication drops? If the pump malfunctions? The algorithm must include logic to detect these failures and transition to a safe state, which requires additional computational resources for monitoring and error detection. For instance, some systems revert to a manual basal rate in case of sensor failure.

- Regulatory Compliance: All integration points and data flows must comply with stringent medical device regulations (e.g., FDA, CE mark), adding layers of testing, documentation, and validation overhead that consume significant engineering and computational resources during development.

The rise of open-source AP initiatives like OpenAPS and Loop has highlighted both the potential and the challenges of system integration, often relying on reverse-engineered protocols and a strong community effort to achieve interoperability (Wikipedia contributors, 2024, ‘OpenAPS’). Commercial systems like the MiniMed 780G have achieved robust integration by controlling the entire ecosystem from sensor to pump (Wikipedia contributors, 2024, ‘MiniMed 780G’).

4. Validation Processes

The development of autonomous health systems, especially those directly impacting life-sustaining functions like glucose regulation, mandates an exceptionally rigorous and multi-layered validation process. This systematic evaluation ensures not only the efficacy and optimal performance of the control algorithms but, more critically, their unequivocal safety and reliability across a diverse range of real-world scenarios.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

4.1 Simulation Studies

Simulation studies constitute the foundational and initial stage of validation, offering a cost-effective and ethically sound environment for extensive testing before any human involvement. These studies provide an invaluable platform to evaluate algorithm performance and robustness under a wide array of meticulously controlled conditions.

- In Silico Patient Simulators: Highly sophisticated mathematical models, such as the FDA-accepted UVa/Padova T1D simulator, are employed to create ‘virtual patients.’ These simulators encompass detailed physiological dynamics of glucose-insulin interaction, meal absorption, exercise effects, and inter-individual variability. They are calibrated to represent cohorts of diverse patient populations (e.g., varying age, weight, insulin sensitivity).

- Scenario Generation: Simulations are designed to test the algorithm’s response to an exhaustive range of scenarios, including:

- Standardized Meals: Various carbohydrate loads, meal timings, and compositions.

- Unannounced or Miscalculated Meals: Crucial for assessing robustness when patient input is imperfect.

- Exercise Events: Different intensities, durations, and timings (e.g., post-meal, fasted).

- Stress and Illness: Physiological responses that can significantly alter glucose levels.

- Sensor Noise and Dropouts: Simulating real-world CGM inaccuracies and temporary signal loss.

- Insulin Pump Malfunctions: Occlusions, delivery failures, or battery depletion.

- Variability in Insulin Sensitivity: Simulating physiological changes over the day or across different individuals.

- Key Performance Metrics: Algorithms are evaluated against a comprehensive set of metrics:

- Time In Range (TIR): Percentage of time glucose is within the target (e.g., 70-180 mg/dL).

- Time Below Range (TBR): Percentage of time glucose is in hypoglycemic ranges (<70 mg/dL, often with sub-categories like <54 mg/dL).

- Time Above Range (TAR): Percentage of time glucose is in hyperglycemic ranges (>180 mg/dL, often with sub-categories).

- Glucose Variability: Standard deviation of glucose, Mean Absolute Glucose Deviation, M-value, CONGA (Continuous Overall Net Glycemic Action).

- Hypoglycemia Event Rate and Severity: Number and depth of low glucose episodes.

- Insulin Dosing Accuracy: Comparison of delivered insulin to theoretical optimal doses.

- Robustness Indices: Measures of how well the algorithm performs under perturbed conditions.

Simulation studies allow developers to rapidly iterate on algorithm design, identify potential safety flaws, and optimize performance before proceeding to more expensive and resource-intensive clinical testing. They are also crucial for regulatory agencies, providing a body of evidence for initial safety assessments.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

4.2 Pre-Clinical and Clinical Trials

Following successful and extensive simulation, algorithms progress through several stages of real-world testing involving biological systems, culminating in human clinical trials.

4.2.1 Pre-clinical (Animal) Studies

While less common for purely algorithmic changes in AP systems (as opposed to new sensor or pump hardware), pre-clinical studies in animal models (e.g., diabetic pigs, dogs) might be employed for entirely novel insulin formulations, sensor technologies, or highly experimental control strategies where safety in humans is particularly uncertain. These studies assess basic feasibility, biocompatibility, and preliminary efficacy in a controlled biological setting.

4.2.2 Clinical Trials

Clinical trials are the definitive stage of validation, assessing the safety, efficacy, and usability of the system in human participants. These trials are meticulously designed, ethically overseen, and typically progress through phases:

- Phase I/Feasibility Studies: Small-scale trials (e.g., 5-10 participants) often conducted in a controlled inpatient setting (e.g., hospital metabolic ward). The primary goal is to establish preliminary safety, assess basic functionality, and refine initial algorithm parameters. Participants are closely monitored, often with frequent blood draws for laboratory glucose confirmation.

- Phase II/Pilot Studies: Larger trials (e.g., 20-50 participants) to evaluate efficacy in more diverse, outpatient settings over slightly longer durations (e.g., weeks to months). These studies aim to optimize algorithm parameters, compare different control strategies, and gather initial data on usability and patient acceptance. Participants manage the system in their home environments with remote monitoring.

- Phase III/Pivotal Trials: Large-scale, often multi-center, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving hundreds of participants over extended periods (e.g., 6-12 months). These trials compare the AP system against standard-of-care (e.g., multiple daily injections or conventional insulin pump therapy with manual adjustments). The primary endpoints typically include improvements in Time In Range, reductions in hypoglycemia, and sometimes HbA1c. Secondary endpoints encompass quality of life measures, patient satisfaction, and safety outcomes. These trials provide the robust evidence required for regulatory approval.

- Regulatory Pathways: Medical devices, including AP systems, are subject to rigorous regulatory oversight by bodies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA). For novel AI-driven systems, the regulatory process can be complex, involving pre-market approval (PMA) or de novo classification. The concept of Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) is particularly relevant, recognizing that software itself can be a medical device. Regulators demand extensive documentation on algorithm design, risk management, cybersecurity, and performance data from simulations and clinical trials.

4.2.3 Real-World Evidence (RWE) and Post-Market Surveillance

Even after regulatory approval, validation continues. Real-world evidence (RWE) collected from deployed systems provides invaluable insights into long-term performance, rare adverse events, and diverse usage patterns that may not have been fully captured in clinical trials. Continuous monitoring of system performance in the field is essential to identify and address issues promptly. This post-market surveillance involves collecting data on device malfunctions, adverse events, and user feedback. Algorithms may require updates or recalibration based on this real-world data and user feedback to maintain optimal performance and adapt to evolving clinical understanding or patient needs. This iterative improvement process ensures ongoing safety and efficacy.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

4.3 Continuous Monitoring and Updates

The dynamic nature of both patient physiology and technological advancements necessitates that the validation of AP algorithms is an ongoing, rather than a singular, event. Post-deployment, a robust framework for continuous monitoring and systematic updates is indispensable.

- Remote Monitoring and Data Collection: Deployed AP systems continuously generate vast amounts of data—CGM readings, insulin deliveries, patient inputs, system alerts, and internal operational logs. This data, anonymized and aggregated, is crucial for post-market surveillance and understanding real-world performance. Secure and compliant data transmission channels are essential.

- Performance Analytics: Specialized analytics platforms are used to analyze this real-world data to identify trends, detect anomalies, assess population-level efficacy, and pinpoint areas for improvement. This includes tracking key metrics like TIR, TBR, TAR, and identifying specific scenarios (e.g., certain meal types, exercise patterns) where the algorithm may be suboptimal.

- Adverse Event Reporting: A stringent system for reporting and investigating adverse events (e.g., severe hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia requiring hospitalization, device malfunctions) is mandatory. These reports feed back into the risk management process and can trigger algorithm reviews or updates.

- Adaptive Algorithm Evolution: As more real-world data becomes available, developers can leverage it to further train and refine machine learning components, update physiological models, or adjust control parameters. This enables algorithms to ‘learn’ and improve over time, making them more personalized and robust.

- Over-the-Air (OTA) Updates: Modern AP systems are designed to receive software updates remotely, similar to smartphone updates. This allows developers to deploy bug fixes, security patches, and algorithmic enhancements to users efficiently and safely. Rigorous testing of these updates (including regression testing) is crucial before deployment.

- Version Control and Audit Trails: Maintaining strict version control for algorithms and a comprehensive audit trail of all changes and deployments is essential for regulatory compliance and for troubleshooting any issues that may arise. Transparency regarding updates and their rationale is also important for patient and clinician trust.

This continuous cycle of data collection, analysis, refinement, and update ensures that AP systems remain at the cutting edge of care while upholding the highest standards of safety and efficacy throughout their lifecycle.

5. Ethical Considerations

The integration of artificial intelligence into autonomous health systems, while promising revolutionary advancements, introduces a complex web of profound ethical considerations that demand careful scrutiny, robust frameworks, and ongoing dialogue among stakeholders. These concerns extend beyond mere technical functionality to encompass patient rights, societal equity, and the very nature of human-machine interaction in healthcare.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

5.1 Patient Autonomy and Consent

The deployment of AI in healthcare fundamentally reconfigures the traditional patient-clinician relationship and raises critical questions about patient autonomy and informed consent.

- Nature of Informed Consent: Patients must be provided with comprehensive and comprehensible information about how AI systems function. This goes beyond the traditional consent for a drug or surgery, as AI systems are dynamic, adaptive, and can operate with a degree of opacity (the ‘black box’ problem). Patients need to understand the AI’s capabilities, limitations, the data it collects, how decisions are made (or learned), and the potential risks and benefits involved.

- Understanding Algorithmic Decisions: Given the complexity of algorithms, especially those involving deep learning or reinforcement learning, explaining their precise decision-making process to a layperson (or even many clinicians) can be challenging. The ‘right to explanation’ is an emerging ethical principle, suggesting that patients should be able to understand the rationale behind an AI’s recommendation or action, particularly if it deviates from expected norms or leads to an adverse outcome.

- Patient Control vs. Automation: While AP systems aim for autonomy, patients retain agency. They must be able to override the system, provide manual inputs (e.g., for unannounced meals), or disconnect if they choose. The balance between full automation and patient control is crucial for maintaining a sense of autonomy and preventing learned helplessness. For instance, some patients prefer a ‘hybrid’ closed-loop system where they still bolus for meals, while others desire a fully automated experience.

- Trust and Understanding: For patients to trust an autonomous system, they need to understand its reliability and limitations. A lack of transparency can erode trust, leading to non-adherence or psychological distress.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

5.2 Data Privacy and Security

Autonomous health systems are inherently data-intensive, handling highly sensitive personal health information (PHI) continuously. This necessitates exceptionally robust measures to protect patient privacy and prevent unauthorized access or misuse of data.

- Scope of Data Collection: AP systems collect intimate details about a patient’s life: continuous glucose levels, insulin dosages, meal timings, activity levels, sleep patterns, and potentially even stress indicators. This forms a digital footprint of their health and lifestyle.

- Regulatory Compliance: Strict adherence to data protection regulations is paramount. In the U.S., the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) governs the use and disclosure of PHI. In Europe, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) imposes stringent requirements on data processing, storage, and cross-border transfer. Similar regulations exist globally.

- Anonymization and Pseudonymization: Techniques to de-identify or pseudonymize data are crucial for research and development purposes to protect individual identities while still allowing for valuable insights. However, complete anonymization of highly granular, continuous physiological data can be technically challenging.

- Cybersecurity Risks: Autonomous medical devices connected to the internet (or even locally via Bluetooth) are vulnerable to cyberattacks. A breach could lead to:

- Data Theft: Sensitive health data falling into the wrong hands.

- Data Manipulation: Altering glucose readings or insulin delivery commands, potentially leading to severe harm (e.g., overdose or underdose of insulin).

- Denial of Service: Disabling the device, leaving the patient without essential care.

- Secure Infrastructure: Robust security measures must be implemented across the entire ecosystem: secure data storage (encryption at rest), secure data transmission (encryption in transit), secure authentication mechanisms, and regular security audits and vulnerability assessments. The entire supply chain of software components must also be secured.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

5.3 Accountability and Liability

Determining accountability and liability in the event of system failures, adverse outcomes, or misjudgments by an AI algorithm is a complex and evolving legal and ethical challenge. The traditional lines of responsibility are blurred when an autonomous system makes decisions.

- Who is Responsible?: If an AP system causes severe hypoglycemia due to an algorithmic error, who bears the liability?

- The Manufacturer/Developer: Did they design, test, and validate the algorithm adequately? Were software updates properly implemented and tested?

- The Healthcare Provider/Clinician: Did they properly prescribe, configure, and educate the patient on the system’s use? Did they monitor the patient adequately?

- The Patient/User: Did they use the device as intended? Were their manual inputs accurate (e.g., carbohydrate counting)?

- The Regulator: Were the approval processes sufficiently rigorous?

- ‘Black Box’ Problem and Causation: Proving causation can be exceptionally difficult, especially with complex, non-deterministic AI models. If an algorithm’s decision-making process is opaque, it becomes harder to pinpoint the exact cause of a failure.

- Evolving Legal Frameworks: Existing legal frameworks for medical device liability may not fully encompass the unique characteristics of AI-driven autonomous systems. New regulations or interpretations may be required to address the distribution of responsibility.

- Shared Responsibility: It is likely that accountability will be distributed among multiple parties, depending on the specific circumstances of the failure. Clear guidelines and robust traceability mechanisms (e.g., audit logs of algorithmic decisions) are necessary to navigate these complex situations.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

5.4 Bias and Fairness

AI algorithms, if not meticulously developed and deployed, can inadvertently perpetuate and even amplify existing societal biases present in training data, leading to unequal treatment and exacerbating health disparities across different patient populations.

- Bias in Training Data: If the datasets used to train and validate AI algorithms are not representative of the diverse patient population (e.g., predominantly composed of data from a specific ethnic group, socioeconomic status, or gender), the algorithm may perform suboptimally or even dangerously for underrepresented groups. For instance, an algorithm trained mainly on data from white males might misinterpret glucose responses in women or individuals of different ethnic backgrounds due to physiological differences (e.g., hormonal influences, genetic variations in drug metabolism).

- Algorithmic Design Bias: Even with diverse data, the design choices within the algorithm (e.g., specific features selected, weighting of certain outcomes in the cost function) can introduce bias. For example, prioritizing hypoglycemia avoidance above all else might lead to consistently higher glucose levels (hyperglycemia) for certain groups.

- Impact on Health Equity: Biased AI in healthcare can lead to unequal access to effective treatments, suboptimal health outcomes, and a deepening of existing health inequities. This is particularly concerning in chronic disease management, where long-term disparities can have severe consequences.

- Mitigation Strategies: Addressing bias and ensuring fairness requires a multi-pronged approach:

- Diverse Data Collection: Actively seeking and incorporating representative datasets from various demographics, ethnicities, genders, and socioeconomic backgrounds.

- Fairness Metrics: Developing and applying quantitative metrics to assess algorithmic fairness (e.g., disparate impact, equal opportunity) across different subgroups.

- Explainable AI (XAI): Tools and techniques that make AI decisions more transparent can help identify and audit potential biases. If the algorithm’s rationale for a decision can be understood, biases become easier to detect.

- Human Oversight and Auditing: Continuous monitoring and regular auditing of AI system performance in real-world settings by human experts can help identify emerging biases.

- Ethical AI Development Principles: Adhering to principles of fairness, accountability, and transparency throughout the AI development lifecycle.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

5.5 Transparency and Explainability (XAI)

Closely related to patient autonomy and bias, the ‘black box’ problem of complex AI models (particularly deep learning and sophisticated RL) poses a significant ethical hurdle. For both patients and clinicians, understanding why an AI system made a particular decision is crucial.

- Clinical Adoption: Clinicians are unlikely to fully trust or integrate AI tools into their practice if they cannot understand or explain their rationale to patients or their colleagues. This is essential for clinical accountability and shared decision-making.

- Patient Engagement: Patients need to understand how the system is working and why it’s taking certain actions (e.g., delivering a large bolus or suspending insulin). This builds confidence and compliance.

- Debugging and Improvement: For developers, explainability is vital for debugging errors, identifying unintended biases, and improving algorithm performance. Without it, fixing issues in complex models can be a trial-and-error process.

- Regulatory Scrutiny: Regulators are increasingly demanding evidence of explainability, especially for high-risk medical devices, to ensure safety and allow for post-market analysis in case of adverse events.

Methods for achieving XAI include post-hoc interpretability techniques (e.g., LIME, SHAP, feature importance analysis), inherently interpretable models (e.g., decision trees, simpler rule-based systems), and visualizations of model behavior. The development of robust XAI for clinical AI is an active area of research.

6. Broader Applications of AI in Healthcare

While this report has focused primarily on control algorithms within artificial pancreas systems for Type 1 diabetes management, the underlying principles, technological advancements, and ethical considerations discussed extend across a vast and rapidly expanding landscape of AI applications in healthcare. AI is poised to revolutionize almost every facet of medicine, from early disease detection to personalized interventions and public health management.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

6.1 Disease Detection and Diagnosis

AI algorithms are demonstrating remarkable capabilities in analyzing complex medical data to identify diseases, often achieving accuracy levels comparable to or exceeding human experts, and frequently providing earlier diagnoses.

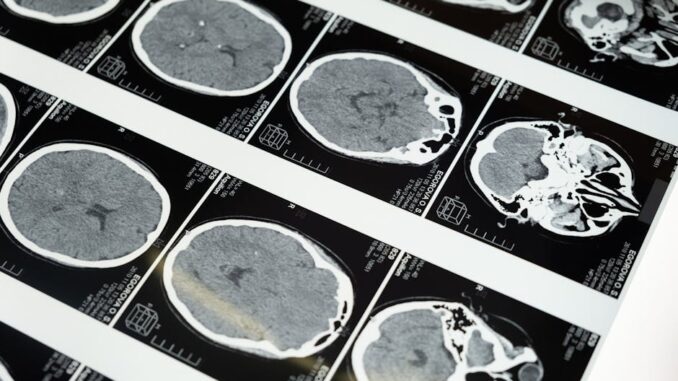

- Medical Imaging Analysis: One of the most mature applications. Deep learning models, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), excel at interpreting medical images such as X-rays, CT scans, MRIs, and pathology slides. Examples include:

- Radiology: Detecting cancerous lesions in mammograms, lung nodules in CT scans, or neurological abnormalities in MRIs. AI can triage urgent cases, reduce radiologist workload, and improve diagnostic consistency.

- Ophthalmology: Identifying diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, and macular degeneration from retinal scans, often in underserved areas lacking specialists.

- Pathology: Analyzing digital pathology slides to diagnose cancer types and grades with high precision, assisting pathologists in complex cases.

- Dermatology: Classifying skin lesions as benign or malignant from dermatoscopic images, aiding in early melanoma detection.

- Early Warning Systems: AI models analyze continuous patient data (e.g., vital signs, lab results, electronic health records (EHR)) to predict the onset of acute conditions like sepsis, cardiac arrest, or acute kidney injury, enabling timely intervention.

- Genomic Analysis: AI assists in analyzing vast genomic datasets to identify disease-associated genes, predict disease susceptibility, and diagnose rare genetic disorders, paving the way for precision medicine.

- Natural Language Processing (NLP) for EHRs: NLP techniques can extract structured information from unstructured clinical notes in EHRs, helping to identify patient cohorts for research, flag potential diagnoses, or identify adverse drug reactions.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

6.2 Drug Discovery and Development

Machine learning models are significantly accelerating and de-risking the arduous and expensive process of drug discovery and development, from identifying potential therapeutic targets to optimizing clinical trial designs.

- Target Identification and Validation: AI can analyze vast biological databases (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics) to identify novel disease targets and predict their relevance to disease pathways, thereby focusing research efforts more effectively.

- Lead Identification and Optimization: ML algorithms predict the binding affinity, efficacy, and toxicity of millions of chemical compounds, rapidly screening vast virtual libraries to identify promising ‘lead’ compounds. This dramatically reduces the need for expensive and time-consuming wet-lab experiments.

- De Novo Drug Design: AI can even generate novel molecular structures with desired properties, rather than just screening existing ones.

- Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) Prediction: ML models can predict how a drug will be absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted (PK) and its biochemical and physiological effects (PD), optimizing dosing strategies.

- Clinical Trial Design and Optimization: AI can analyze patient data to identify ideal candidates for clinical trials, predict patient response to treatment, and optimize trial design (e.g., dose-response, patient stratification), potentially shortening trial durations and reducing costs.

- Drug Repurposing: AI can identify existing drugs that might be effective for new indications, accelerating the path to market for treatments.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

6.3 Personalized Treatment Plans

AI systems are increasingly capable of analyzing comprehensive patient data to recommend highly individualized treatment plans, moving beyond generalized guidelines to optimize therapeutic outcomes for each unique patient.

- Precision Oncology: Integrating genomic data, proteomic profiles, and clinical characteristics, AI helps oncologists select the most effective targeted therapies or immunotherapies for individual cancer patients, predicting response and minimizing adverse effects.

- Chronic Disease Management (Beyond T1D): For conditions like heart failure, asthma, or hypertension, AI can analyze continuous monitoring data, lifestyle factors, and medication adherence to provide personalized recommendations for lifestyle changes, medication adjustments, or timely interventions to prevent exacerbations.

- Mental Health Interventions: AI-powered chatbots and virtual therapists can provide personalized cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) exercises, monitor mood, and offer support, potentially increasing access to mental health care.

- Dietary and Lifestyle Recommendations: AI can analyze individual metabolic responses, microbiome data, and lifestyle habits to provide tailored dietary advice and exercise regimens for weight management, blood glucose control (for T2D), or cardiovascular health.

- Drug Dosing Optimization: AI can recommend patient-specific drug dosages based on their genetics, renal/hepatic function, concurrent medications, and other individual factors, minimizing adverse drug reactions and maximizing efficacy.

- Predicting Treatment Response: For various conditions, AI models can predict which patients are most likely to respond to a particular treatment, helping clinicians make informed decisions and avoid ineffective therapies.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

6.4 Robotics in Healthcare

AI is the driving force behind the increasing sophistication and autonomy of robotics in healthcare, extending beyond surgical assistance.

- Surgical Robotics: AI enhances robotic-assisted surgery (e.g., Da Vinci system) by providing image guidance, optimizing surgical paths, and even potentially performing certain autonomous tasks under human supervision, improving precision and reducing invasiveness.

- Rehabilitation Robotics: AI-powered exoskeletons and robotic limbs can provide highly personalized rehabilitation exercises, adapt to patient progress, and assist individuals with mobility impairments.

- Autonomous Delivery Systems: Robots equipped with AI navigation and object recognition can autonomously transport medications, laboratory samples, and supplies within hospitals, improving efficiency and reducing human contact (Kalaivanan et al., 2025).

- Companion and Social Robots: AI-driven robots are being developed to provide companionship for the elderly, assist with daily living activities, and monitor well-being.

Many thanks to our sponsor Esdebe who helped us prepare this research report.

6.5 Epidemiology and Public Health

AI’s ability to process and analyze large, complex datasets makes it invaluable for population health management and epidemiology.

- Disease Outbreak Prediction: AI models can analyze diverse data sources (e.g., social media trends, travel patterns, climate data, news reports) to predict the emergence and spread of infectious diseases, aiding in public health preparedness.

- Resource Allocation: AI can optimize the allocation of healthcare resources (e.g., hospital beds, staffing, vaccine distribution) during crises or for routine public health planning.

- Population Health Management: Identifying at-risk populations, predicting disease incidence, and designing targeted public health interventions based on demographic, environmental, and clinical data.

The rapid evolution of AI, fueled by increasing computational power, vast data availability, and innovative algorithms, ensures that its impact on healthcare will only continue to grow, ushering in an era of more precise, personalized, and proactive medical care. Initiatives like the MIT Jameel Clinic are dedicated to advancing AI in health and translating these research breakthroughs into clinical practice (Wikipedia contributors, 2024, ‘MIT Jameel Clinic’).

7. Conclusion

Control algorithms stand as the indispensable architects of autonomous health systems, orchestrating the complex interplay of real-time data processing, personalized adaptation, and dynamic decision-making that defines the future of precision medicine. Their profound impact is perhaps nowhere more vividly demonstrated than in the realm of artificial pancreas systems for Type 1 diabetes management, where they adeptly transform continuous glucose readings into intelligent insulin delivery commands, aiming to liberate individuals from the relentless burden of manual glucose regulation.

This report has systematically elucidated the intricate technical landscape of these algorithms, delving into the distinct methodologies of PID, MPC, Fuzzy Logic, and Reinforcement Learning, each offering unique strengths in navigating the unpredictable physiological terrain of the human body. We’ve explored how advanced algorithms meticulously process diverse data inputs—from continuous glucose levels and insulin on board to patient-reported meal composition and physical activity—to achieve unparalleled personalization and adaptability, thereby enhancing therapeutic precision and patient outcomes. However, the path to fully autonomous, universally applicable health systems is not without its formidable obstacles. Significant computational challenges persist, particularly in the demand for real-time data processing on resource-constrained embedded devices, the inherent complexity and dynamic personalization required for physiological modeling, and the intricate technical hurdles of seamless system integration across heterogeneous hardware platforms.

Beyond technical feasibility, the ethical dimensions of deploying AI in healthcare are paramount and necessitate continuous scrutiny. Issues surrounding patient autonomy and informed consent, the inviolable sanctity of data privacy and security, the nascent frameworks for accountability and liability in the event of AI-driven adverse outcomes, and the critical imperative to mitigate algorithmic bias and ensure fairness across diverse patient populations demand proactive and robust solutions. Furthermore, the need for transparency and explainability in complex AI models is crucial for fostering trust among patients and clinicians.

Despite these profound computational challenges and multifaceted ethical considerations, the integration of artificial intelligence into healthcare holds extraordinary promise. Its applications extend far beyond diabetes management, offering transformative potential in disease detection and diagnosis, accelerating the notoriously arduous process of drug discovery and development, facilitating the creation of truly personalized treatment plans, advancing the capabilities of robotics in clinical settings, and enhancing public health surveillance and resource allocation. The vision of a future where AI empowers clinicians with unparalleled insights and provides patients with autonomous tools for optimal health management is increasingly within reach. Ongoing, collaborative research and development efforts, coupled with robust regulatory frameworks and an unwavering commitment to ethical principles, are not merely essential but absolutely imperative to address these challenges comprehensively and to harness the full, transformative potential of AI in ushering in a new era of healthcare—one characterized by unprecedented precision, proactive intervention, and profound improvements in human well-being.

8. References

- Bellazzi, R., Zini, G., & Sartori, L. (2001). Automated closed-loop control of diabetes: the artificial pancreas. Bioelectronic Medicine, 1(1), 1-10.

- Bequette, B. W. (2013). Algorithms for a closed-loop artificial pancreas: The case for model predictive control. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, 7(6), 1632-1643. [Retrieved from https://www.ovid.com/journals/jdst/pdf/10.1177/193229681300700624~algorithms-for-a-closed-loop-artificial-pancreas-the-case]

- Chen, H., Paoletti, N., Smolka, S. A., & Lin, S. (2020). MPC-guided imitation learning of neural network policies for the artificial pancreas. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.01283.

- Kalaivanan, N., Muthukumaraswamy, S. A. M., & Balasubramanian, G. (2025). Autonomous multi-robot infrastructure for AI-enabled healthcare delivery and diagnostics. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.26106.

- Sonzogni, B., Manzano, J. M., Polver, M., Previdi, F., & Ferramosca, A. (2024). CHoKI-based MPC for blood glucose regulation in artificial pancreas. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.17157.

- Tanzanakis, A., & Lygeros, J. (2023). Data-driven robust reinforcement learning control of uncertain nonlinear systems: Towards a fully-automated, insulin-based artificial pancreas. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.04503.

- Wikipedia contributors. (2024). Automated insulin delivery system. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Automated_insulin_delivery_system

- Wikipedia contributors. (2024). Control of Artificial Pancreas Systems. In YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rrtPn6GKMlU

- Wikipedia contributors. (2024). Dexcom CGM. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dexcom_CGM

- Wikipedia contributors. (2024). CLOSING THE LOOP: THE LATEST ON ARTIFICIAL PANCREAS SYSTEMS. In ONdrugDelivery. Retrieved from https://ondrugdelivery.com/closing-the-loop-the-latest-on-artificial-pancreas-systems/

- Wikipedia contributors. (2024). MiniMed 780G. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MiniMed_780G

- Wikipedia contributors. (2024). MIT Jameel Clinic. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MIT_Jameel_Clinic

- Wikipedia contributors. (2024). OpenAPS. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OpenAPS

- Wikipedia contributors. (2024). Open-source artificial intelligence. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open-source_artificial_intelligence

Be the first to comment